Scientist of the Day - Marin Carburi

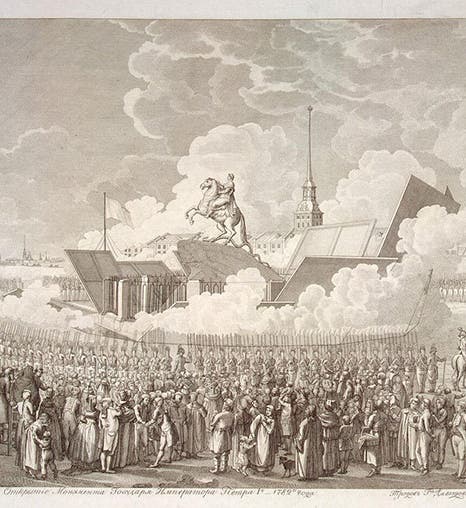

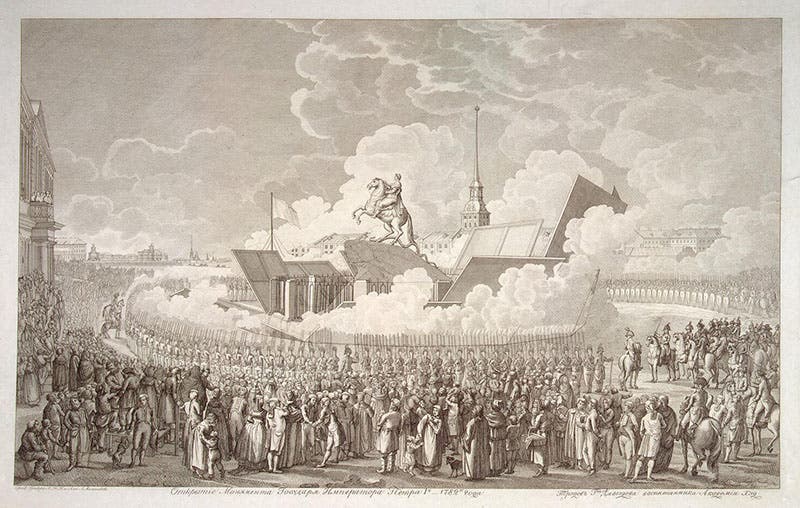

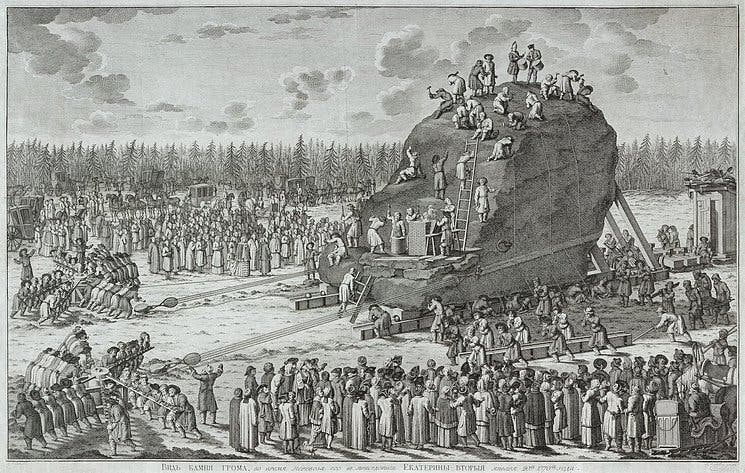

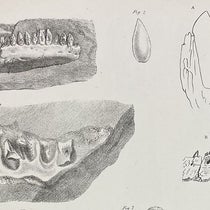

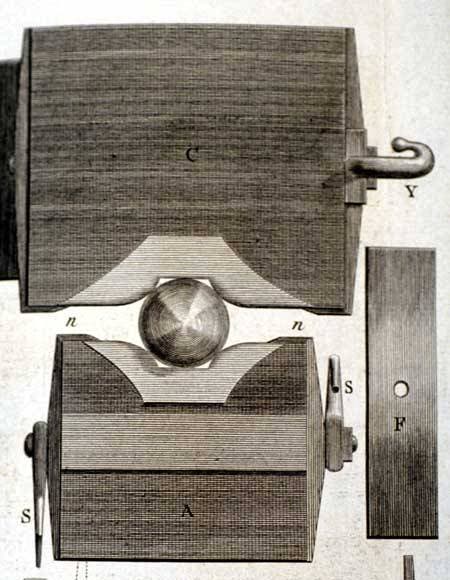

On Aug. 7, 1782, a bronze equestrian statue of Peter the Great was unveiled with great pomp in St. Petersburg in Russia (see first image above). The statue, cast by French sculptor Etienne Falconet, was and is impressive enough, but for many, the real eye-catcher was the large granite stone on which the horse was mounted (second image). The stone base had been shaped from an immense granite boulder that had been discovered in 1768 in the woods north of St. Petersburg, about 6 miles from the Gulf of Finland. It is estimated that initially the Thunder Stone, as it came to be called, was some 40 feet long, 25 feet side, and 21 feet tall, and weighed some 1800 tons. That means it weighed about 1300 tons more than any of the obelisks moved by the ancient Egyptians or Romans; to transport it would require considerable technological ingenuity. The challenge fell to Marin Carburi, a Greek engineer working in Russia for Catherine the Great. Large monoliths had always been moved overland by rollers, but it was doubtful that rollers could support such a colossal weight. Carburi decided to lay a track to the sea, and he mounted the Thunder Stone on a gigantic sled of sorts, and on the bottom of the sled and on the top of the rails he embedded metal tracks, and between the opposed tracks he inserted 6" bronze balls to carry the weight and allow the stone to slowly roll down the track. Carburi had invented the ball bearing (third image). Even with the help of the bearings, and two fully manned capstan winches, it was slow going, with the Thunder Stone progressing at the rate of a little over a mile per month for 5 months. Catherine the Great, who was the guiding force behind the creation of the monument to Peter, visited the stone procession in the woods on Jan. 20, 1770, and an engraving records the event (fourth image). If you look closely, you can see the track sections being brought forward from the rear, and the bronze balls being moved from back to front as well and placed in the tracks

Carburi later published a book on his adventures with the Thunder Stone, which we displayed in our Centuries of Civil Engineering exhibition in 2002. Incidentally, the Library of Congress catalogues this book under the name Marinos Charboures, which is not a name that Carburi ever used, nor does it appear on the title page of his book; nevertheless, that is the name you must use if you wish to look up the book.

Our last image is a painting of the Bronze Horseman and the Thunderstone, made in 1879 by Vasily Surikov, which we include because it is so lovely.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.