Scientist of the Day - Mikhail Adams

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

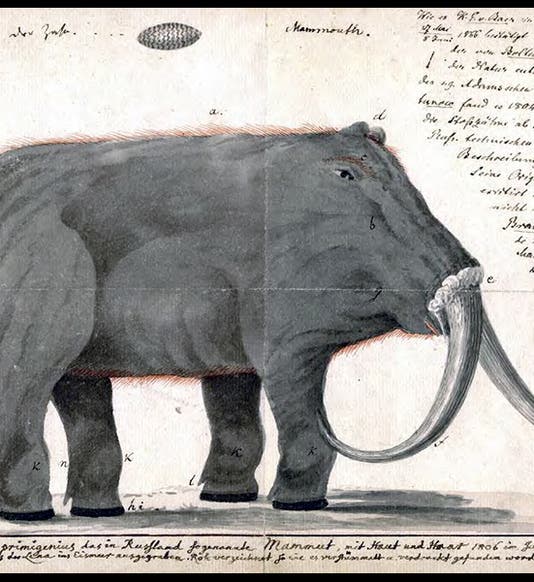

Mikhail Adams, a Russian naturalist, died Mar. 1, 1838; his date of birth is unknown. In fact, very little is known about Adams’ life in general, except for his one memorable feat: in 1806, he recovered the mostly intact carcass of a wooly mammoth, complete with skin and hair, from the Lena River delta in Siberia. The frozen body had first been noticed in 1799, during the brief Siberian summer, as it began to emerge from a bluff along the river, but no naturalist became aware of it until Adams, who had been on a mission to China, passed through a nearby city and heard stories of the find. He led an expedition to the site, gathered up what was left of the skeleton, the skin, and few sackfuls of hair, and shipped everything back to St. Petersburg. Adams was a botanist, not a zoologist or anatomist, but still, it is hard to understand why he made no drawings of the carcass in situ. One other early observer did so, and a copy of his drawing survives (first image), but it is not clear what was observed and what was imagined, although we can tell the trunk was gone when the sketch was made. By the time Adams got there, the tusks were gone as well, sold to an ivory merchant. On his way back, Adams bought two tusks from a dealer, and he was convinced that they were the very ones that had been removed and sold, but they were not.

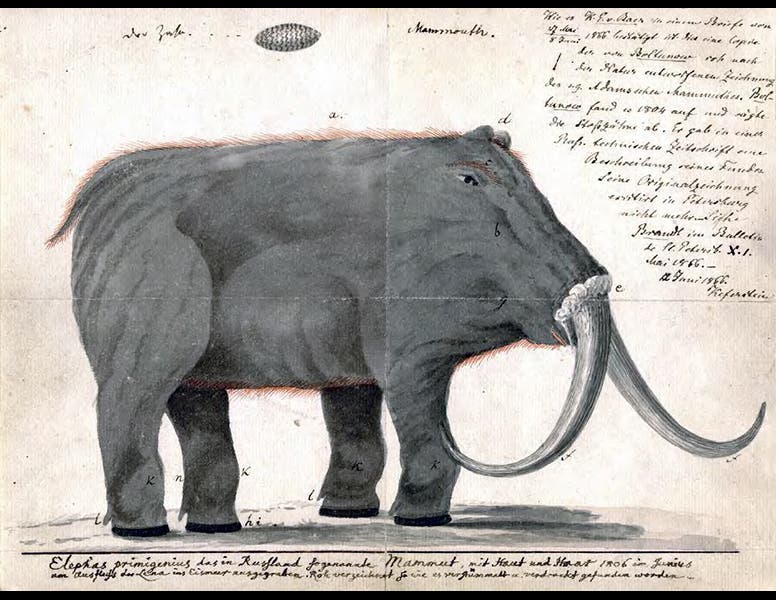

The mammoth remains eventually made their way to St. Petersburg, where the Imperial Academy of Sciences turned to a German naturalist, Wilhelm Gottlieb Tilesius, to reconstruct the animal. Tilesius did a commendable job, except for interchanging the (substitute) tusks, so they pointed upward and outward, instead of down and in. It was at the time the most complete mammoth skeleton known, and would remain so for a century, the extinct proboscid counterpart to the Peale mastodon in Philadelphia. The Siberian mammoth is still on display at the zoological Museum in St. Petersburg (second image) and is almost always referred to as the Adams mammoth.

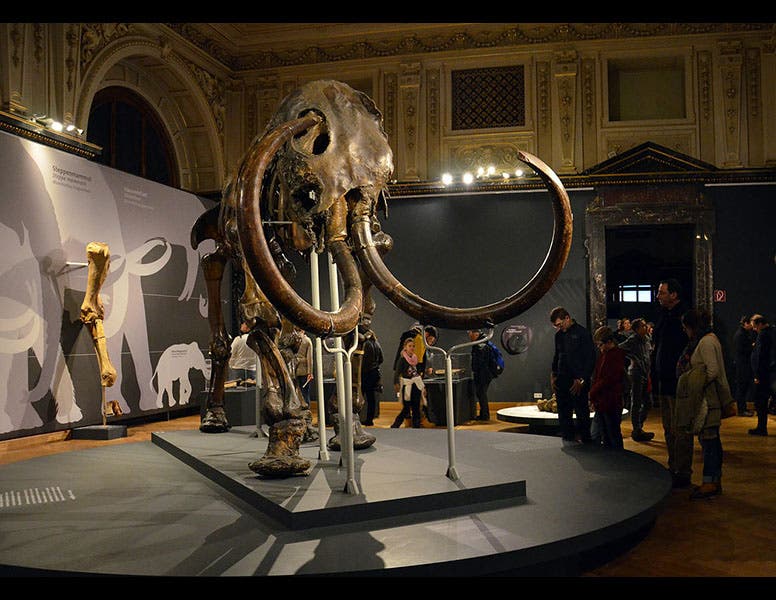

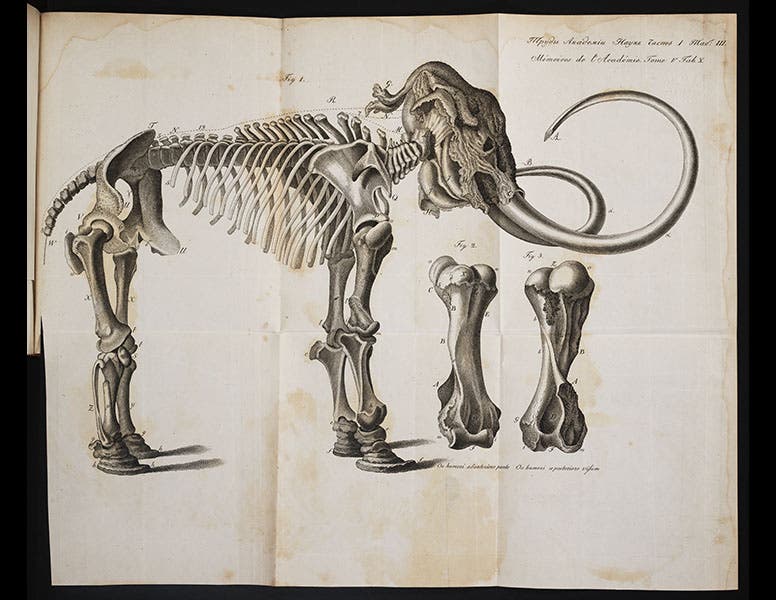

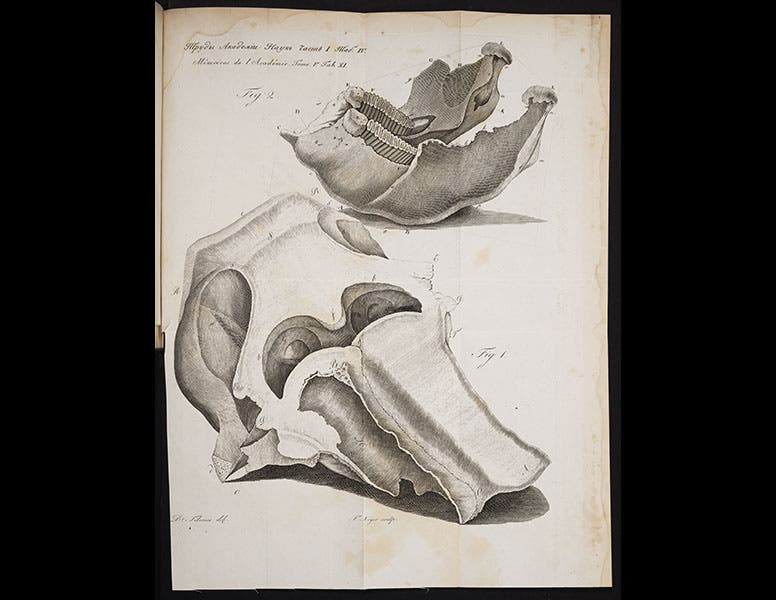

Adams wrote and published an unillustrated account of his expedition in 1807, which we do not have in the Library. Tilesius also wrote a long paper describing the mammoth skeleton, which he published in 1815 in the Memoires of the St. Petersburg Imperial Academy of Sciences. That publication we do have, and the engravings of the complete Adams mammoth skeleton (third image) and the skull (fourth image) are reproduced above.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.