Scientist of the Day - Nathanael Carpenter

Nathanael Carpenter, an English geographer, was born Feb. 7, 1589. Geography was in a curious state in 1625. It was one of the few sciences that was still ruled by two ancient Greek authorities, Ptolemy and Strabo. Ptolemy, a mathematician, had declared that geography was concerned with the whole Earth, with the oecumene, the inhabited part of the globe, and with the mathematical circles and zones that marked and delineated our globe. He declared that chorography, the detailed study of the topography and peoples of particular regions, was not a proper part of geography.

Strabo, on the other hand, preferred regional geography, and his Geographica was distinctly lacking in any kind of a mathematical basis. Carpenter published his Geography Delineated Forth in Two Bookes in 1625, and he strongly argued that Ptolemy and Strabo were both wrong – that geography should be concerned with the whole Earth as well as its parts, and that topography, which Carpenter prefers to the term chorography, should attempt, in its descriptions of regions, to relate regional facts to principles concerning the whole Earth.

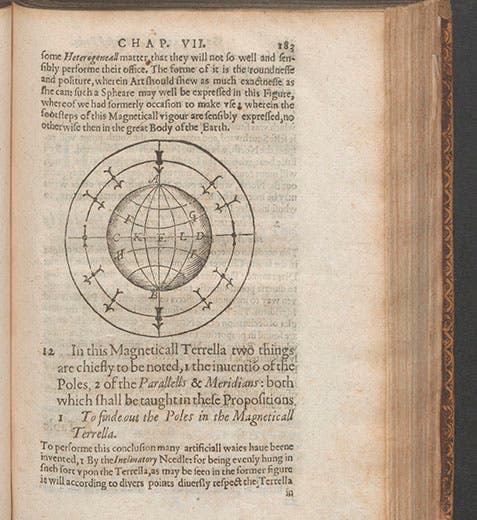

Carpenter even suggested, following William Gilbert, that a study of terrestrial magnetism might provide a unifying principle for geography, and there are abundant references in his book to Gilbert’s notion of an earth rotated by its magnetic properties. He even includes a woodcut of one of Gilbert’s terrellas, miniature round magnets representing the Earth (first image).

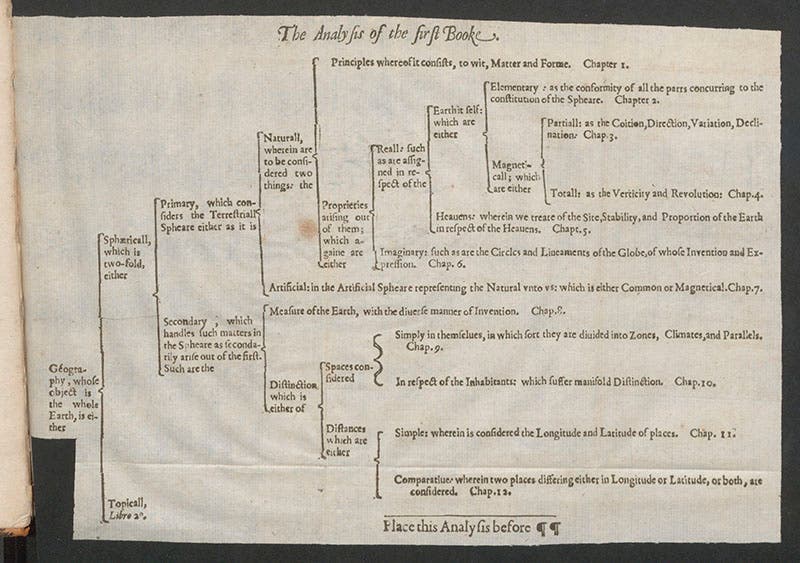

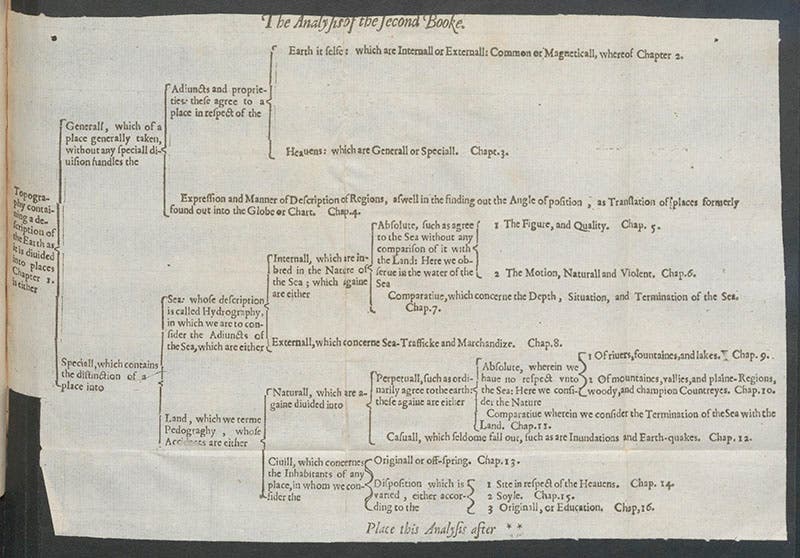

Another interesting feature of Carpenter’s Geography Delineated is its use of Petrus Ramus-like tables, in which in a subject is subdivided by two, again and again, until it is completely broken down into its constituent parts. There is such a table for Geography (third image), and another for Topography (fourth image), in Carpenter’s book.

Carpenter’s Geography Delineated was revolutionary in a number of ways, and it is odd that it was essentially still-born. As far as we can tell, hardly anyone read it, and even when Alexander von Humboldt in the 19th century put Carpenter's magnetic program into practice, he seems to have been unaware of Carpenter and/or his book. Only in the last century has Carpenter finally been recognized as being a pioneer of geographical reform.

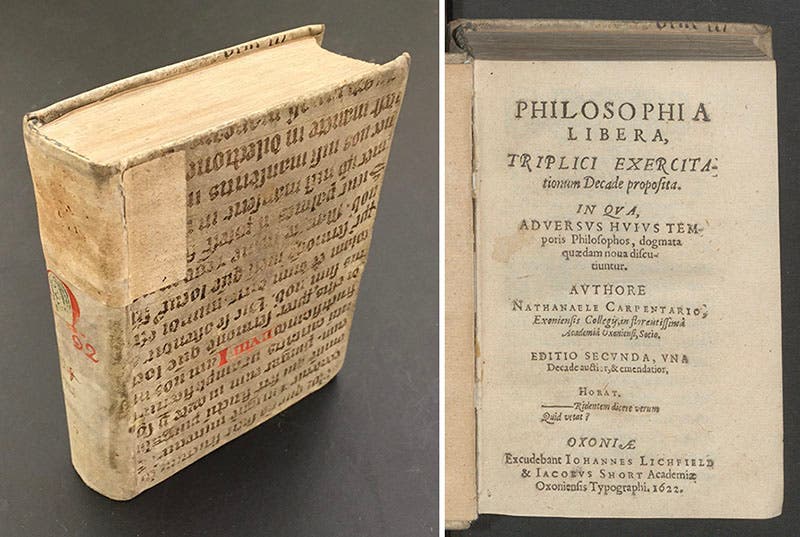

Carpenter wrote another short treatise in 1622, before he wrote his Geography, called Philosophia libera (fifth and sixth images). We have both of his books in our history of science collection. There is no portrait of Carpenter that we know of.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.