Scientist of the Day - Odoardo Beccari

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

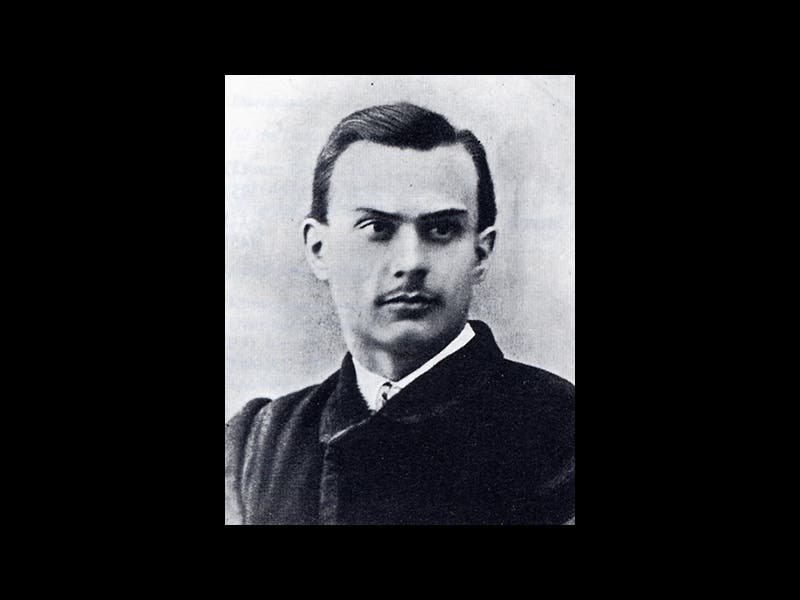

Odoardo Beccari, famous primarily for discovering the giant corpse flower (Amorphophallus titanum), was born on 16 November 1843 in Florence. After attending university in Pisa and Bologna, he left for London, where he studied natural history at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Finding refuge from the city’s smog in Kew’s botanic oasis, the naturalist met many of Britain’s foremost naturalists, from William Jackson Hooker and Joseph Dalton Hooker to Charles Darwin. Perhaps most significantly, Beccari became close friends with James Brooke, the “Rajah of Sarawak,” and accepted his support in launching an expedition to the Indonesian Archipelago. In 1865, Beccari left for Sarawak with fellow Italian naturalist Giacomo Doria (1840 – 1913), and the pair traveled through the region for the next three years collecting plants and animals.

Beccari left Sarawak in 1868 to further his colonial goals (second image). After briefly returning to Europe, he traveled to Ethipia, where he assisted the Italian government in its violent purchase of the Bay of Assab, effectively designating Eritrea as Italian property. Beccari returned to Indonesia in 1877, embarking on a much more ambitious expedition through the archipelago, as well as through India, Malaysia, and New Zealand, accompanied by the ornithologist Luigi D’Albertis. The naturalist published an account of these voyages in his 1902 Nelle Foreste di Borneo, Viaggi e Richerche di un Naturalista—translated into English in 1904 as Wanderings in the Great Forests of Borneo: Travels and Researches of a Naturalist in Sarawak. Interspersed throughout descriptions of plants and animals, Beccari published black and white ethnographic photographs of indigenous peoples. These photographs reek of scientific racism, categorizing humans as specimens for study, ordered largely by their physical appearance and by uninformed, paternalistic judgments of their customs and habits.

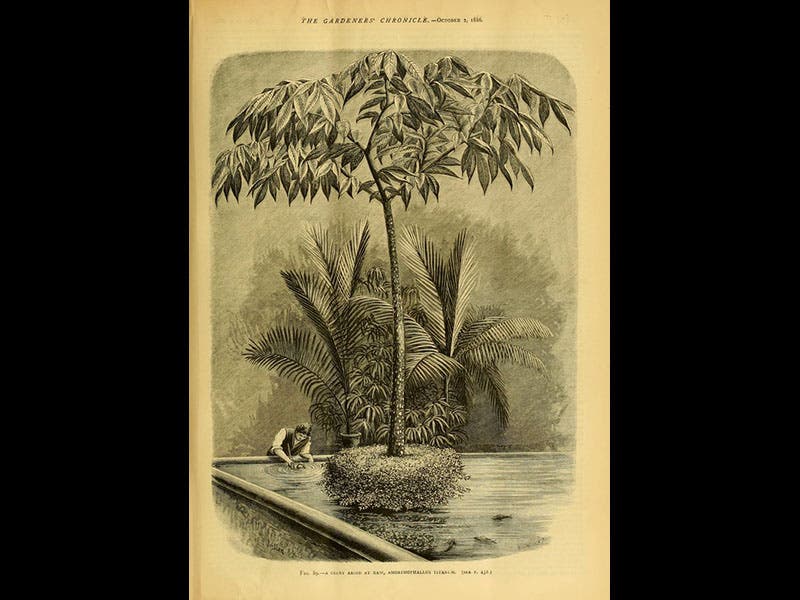

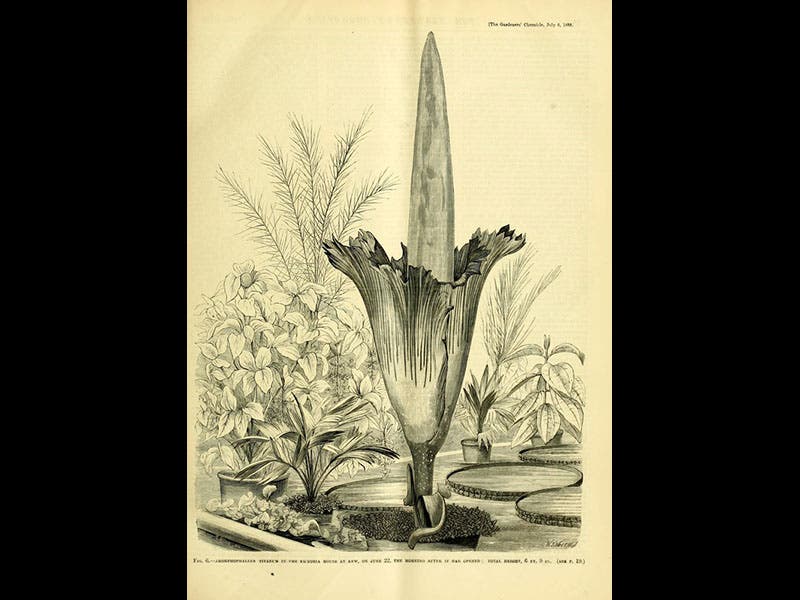

On a short trip to central Sumatra in 1878, Beccari discovered the largest flower in the world—the Amorphophallus titanum, which he originally named the Conophallus. Other naturalists, including Karl Ludwig Blume, had worked with other members of the Amorphophallus tribe decades earlier, but none approached this species in size, rarity, or smell. Although few details of his discovery are known, Beccari immediately sent reports and sketches back to European publications, and news of the stunningly animalistic flower was published in the weekly Gardeners’ Chronicle that year (third image). Beccari provided no acknowledgment of his Sumatran guides and made no reference to indigenous knowledge of the plant in his notes or publications. The first specimen of Amorphophallus titanum bloomed at Kew, where Beccari had started his journey, in 1885, sparking wonder and spectacle as thousands of patrons traveled to see the giant, phallic flower that smelled like rotting flesh (fourth and fifth images). Its bloom cycle lasted for only three days, conjuring up even more excitement about the plant’s extreme rarity.

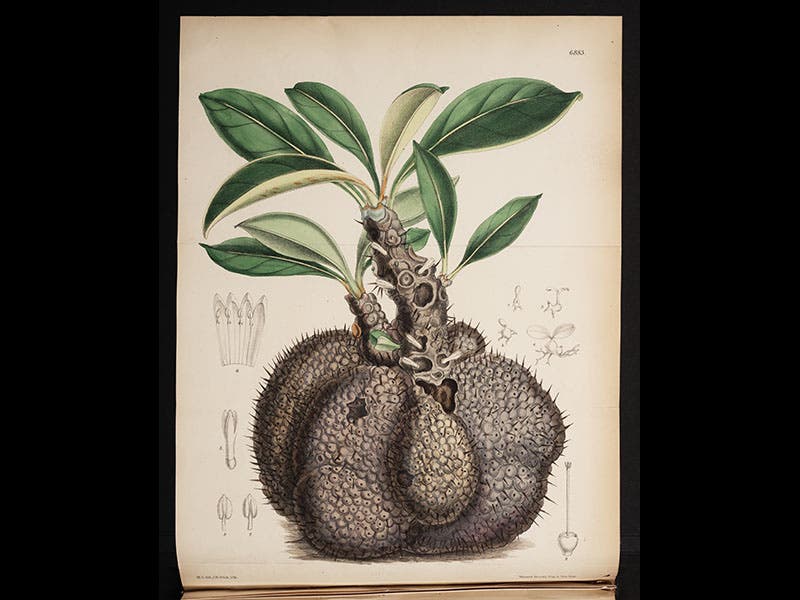

Odoardo Beccari returned to Florence after his 1878 discovery, where he briefly served as Director of the Florence Botanic Garden. The naturalist lived in Italy for the rest of his life, publishing a number of books and articles on Southeast Asian plants, and especially on palms. He died on 25 October 1920. His legacy extended beyond the infamous corpse flower; a number of plants and animals were named after him, including the Myrmecodia beccarii pictured here (sixth image), a plant notorious for its strange symbiotic relationship with ants. While Beccari’s name will forever be affixed to one of the most popular plants in the world—the Amorphophallus titanum continues to bring in thousands of visitors when it blooms in botanic gardens—his work should also be a reminder of natural history’s frequent connection to colonial expansion in the nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries.

Elaine Ayers is a doctoral candidate in the Program in the History of Science at Princeton University, and is the 2017 – 18 80/20 Fellow at the Linda Hall Library. She works on the history of natural history, collecting, and museums in the nineteenth century. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to: eayers@princeton.edu.