Scientist of the Day - Otto Nordenskjöld

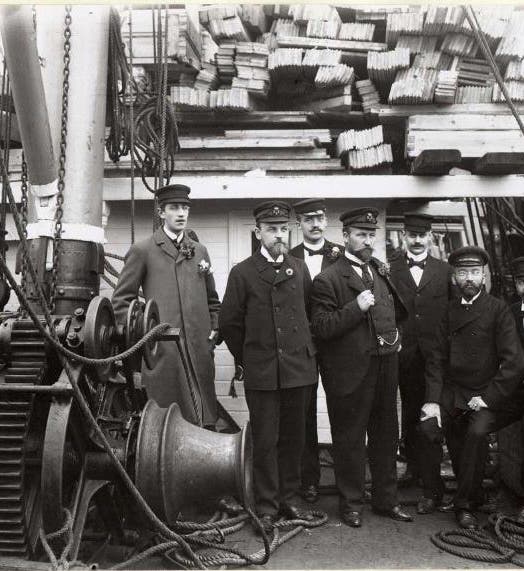

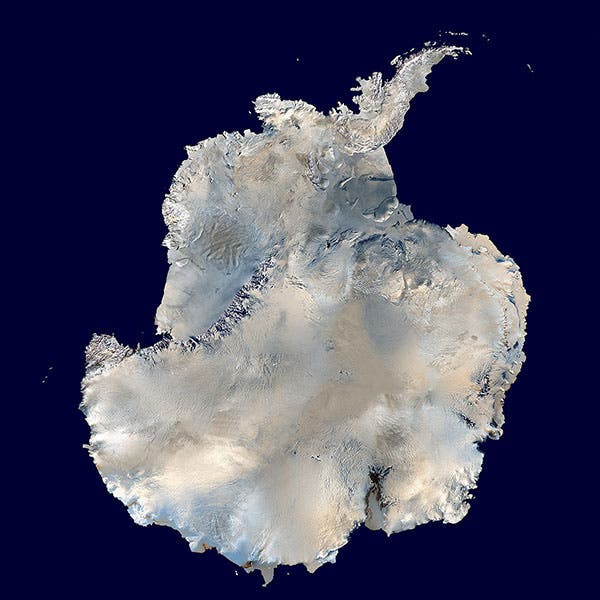

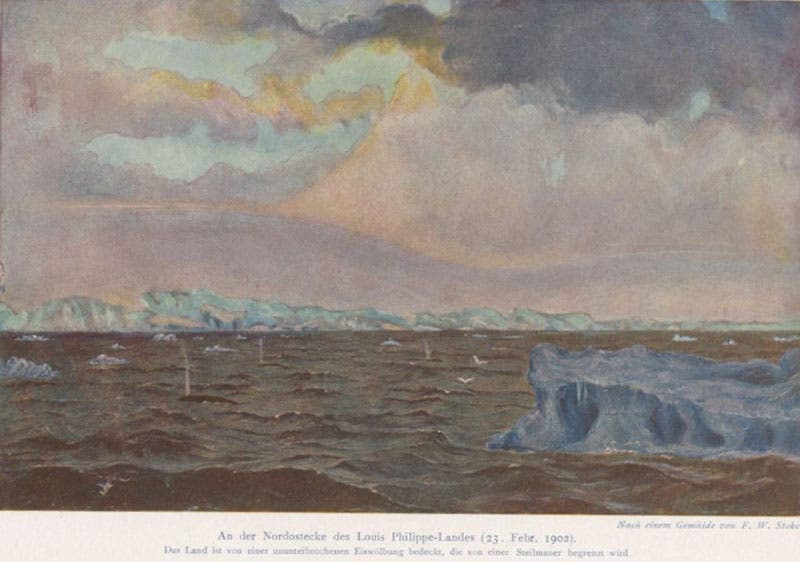

Nils Otto Gustaf Nordenskjöld, a Swedish geographer and polar explorer, was born Dec. 6, 1869. Nordenskjöld organized, led, and raised the funds for a generally unsung expedition to the Antarctic continent, during the early days of the so-called Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration. His expedition was called the Swedish Antarctic Expedition. The mission was to take a ship down into the Antarctic Peninsula, the long finger of land that extends up toward South America (second image, below); to over-winter on one of the islands along the peninsula, and to map the area and collect zoological and geological specimens. The ship was called the Antarctic and carried a crew of 27; Carl Larsen was the ship's captain.

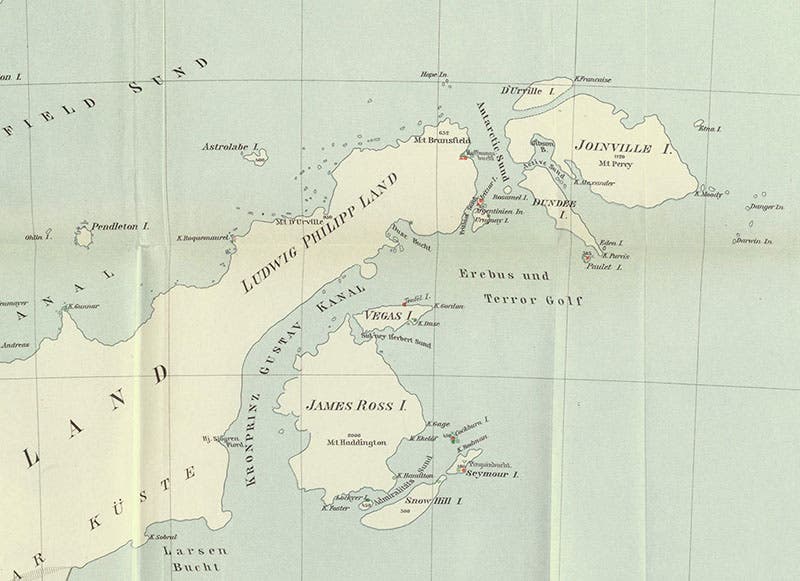

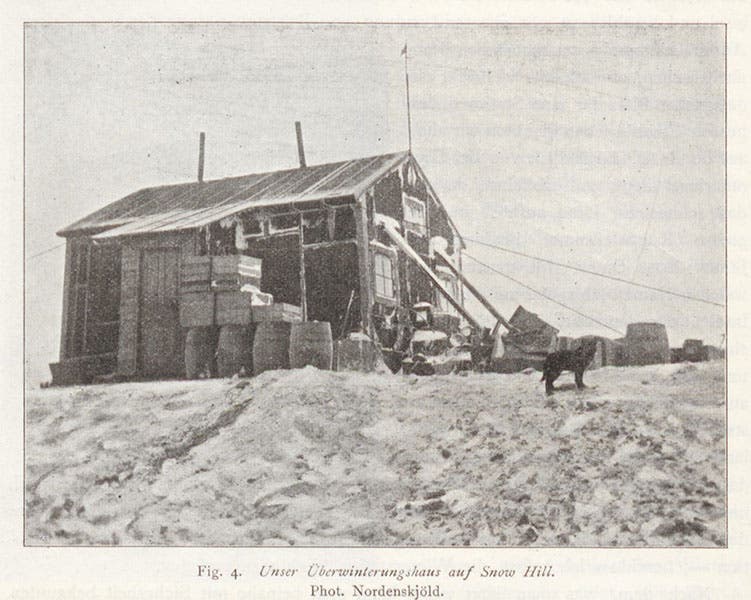

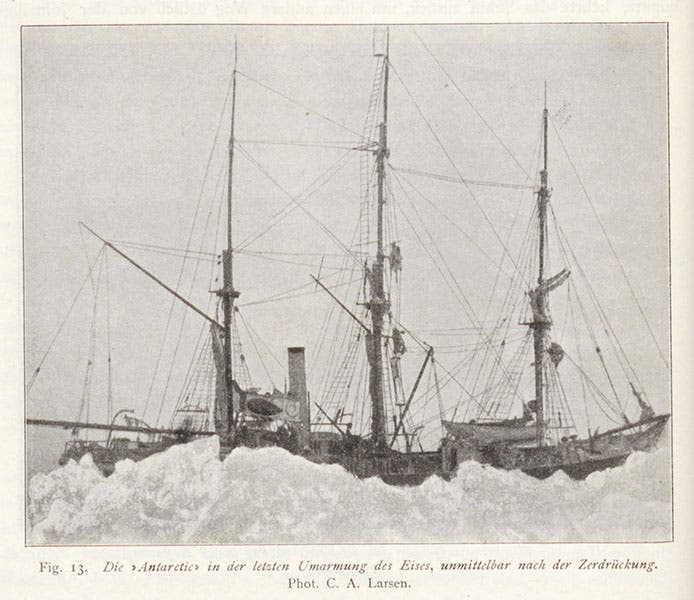

Everything went well at the beginning; six men, including Nordenskjöld, were disembarked on Snow Hill Island to build a winter camp (fourth image, below); the Antarctic then returned to the Falkland Islands and Tierra del Fuego, intending to come back the next summer (January) to pick up the over-wintering crew. However, on the return trip south, the ship ran into dangerous pack ice that had been absent the year before, and it was eventually frozen in (just like Shackleton’s Endurance 13 years later), crushed, and sunk (sixth image, below). The ship's crew escaped to tiny Paulet Island, where they built a stone hut for their own unexpected over-wintering. You can find Snow Hill Island, Paulet Island, and Antarctic Sound, which contained a fallback rendezvous point, Hope Bay, on a map detail we include as our third image, just above.

When the ship did not appear as scheduled in January of 1903, Nordenskjöld and his men battened down for a second winter, for which they were provisionally unprepared. They had to lay in a supply of penguins to provide both food and fuel, an enterprise that sickened Nordenskjöld to his core, since the penguins had no fear whatsoever of humans. Finally, in the fall of 1903, a search party from Hope Bay in Antarctic Sound, at the end of the Peninsula, reached Snow Hill, and not too long after that, two Argentinian officers showed up at the camp, having hiked over from a rescue vessel sent by the Argentinian Navy. And then, even more amazing, Capt. Larsen and five men from the Antarctic tramped into Snow Hill, having trekked first to Hope Bay and then followed directions south to Snow Hill. The Argentinian ship’s crew collected everyone on Snow Hill, sailed back to Paulet Island and picked up the rest of the crew of the Antarctic, and returned to Buenos Aires; the Swedes then headed home on a German vessel. Only one man was lost, a young crewman on the Antarctic who died from a heart ailment.

In spite of the unexpected hardships, the expedition was considered a success, and Nordenskjöld and the crew were hailed by the Swedish public upon their return. Nordenskjöld was offered the position of professor of geography at the University of Gothenburg in 1905, which he accepted, and he spent the next fifteen years writing up the scientific results of the voyage, and paying off the considerable financial debts that they had run up. We have the 8-volume set of the Wissenschaftliche Ergebnisse der Schwedischen Südpolar-Expedition (Scientific Results of the Swedish South-polar Expedition) in our Library (6 volumes bound in 8, to be precise, 1905-1920), as well as three supplemental volumes that were published in 1946. Six of the images that illustrate this post were taken from this work.

Having survived the worst that the south-polar regions could throw at him, Nordenskjöld died in in 1928, at age 58, when he was struck by a bus while crossing the street in Gothenburg.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.