Scientist of the Day - Percival Pott

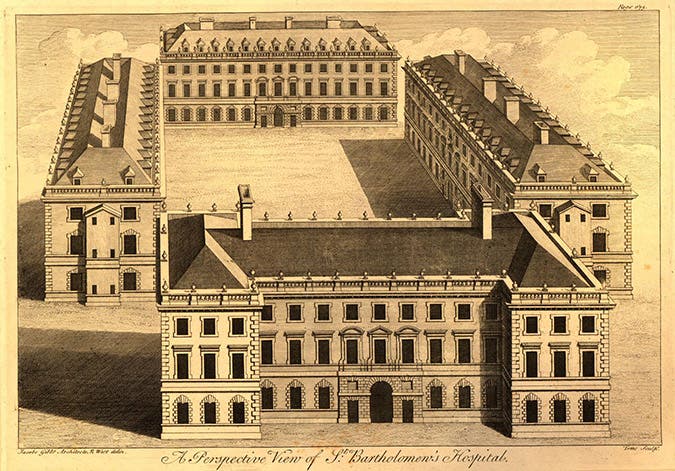

Percival Pott, an English surgeon, was born Jan. 6, 1714. Actually, his birth occurred on the second day of Christmas of 1713, but the English calendar reform of 1752, when England converted to the Gregorian calendar, pushed Pott's birthday up to just beyond the fading sound of drummers drumming and into the year 1714. Pott apprenticed to a barber-surgeon in London and eventually managed to secure a position as assistant surgeon at the venerable St. Bartholomew’s Hospital in London (usually called Barts) in 1745. That same year, the surgeons broke away from the barbers, after three centuries of partnership, and, in their own version of "Knives Out," formed their own guild, the Company of Surgeons. Surgery was beginning to emerge as a socially respectable profession as Pott began his career. We include an engraving of Barts, printed in 1739, as our second image.

Pott became one of the most highly regarded surgeons in mid-to-late-18th century London. We tend to think of John Hunter when we think of 18th-century surgery, and Hunter did eventually become more famous, but that was not true at the time, and Pott is generally regarded as the better practical surgeon. At Barts, he had apprentices and �“dressers,” who paid handsomely for the privilege of learning from Pott, and he gave lectures to students at the hospital. In addition, he had an extensive private practice in his home. Since many of his apprentices and dressers lived in Pott’s home, it must have been a bustling place.

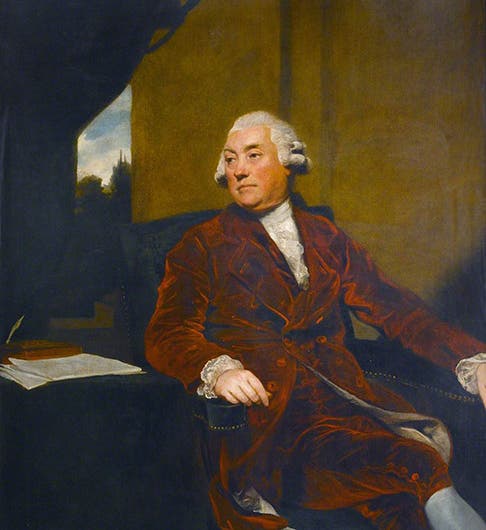

In 1756, Pott fell from his horse and broke his leg badly, and while recuperating, he began writing pamphlets on particular surgical subjects, such as treating hernias, setting broken limbs, and diagnosing wounds to the head. These treatises made extensive use of case studies. Pott kept extensive case records that still survive, which was unusual among surgeons, as he tried to evaluate the best ways to cut for the bladder stone, treat a cancerous breast, or decide whether and when to amputate an injured limb. He recognized that a surgeon walks a delicate wire – he must be an authority figure, forceful and unwavering, but he must be careful not to turn into a bully. One would think that surgery in the 18th-century could well have been a nightmare for both surgeon and patient, with no anesthetics, and infection and gangrene always threatening any open wound. Pott seems to have developed a perspective that was both sympathetic and slightly removed, which was probably essential for him to keep his sanity in a world of pain and death. He was a thoroughly admirable man, and well enough regarded that his portrait was painted by the two most eminent portraitists in 18th-century London: Joshua Reynolds (first image, now in St. Bartholomew's Hospital Museum), and George Romney (third image, that portrait is in the Hunterian Museum in London).

Nearly every modern account of Pott zooms in on one aspect of his career that we have not yet mentioned. Pott is said to have identified the first occupational cancer, when in 1775 he pointed out that a disease of chimney sweeps, known at the time as “sooty warts” but in fact a cancer of the scrotum, was caused by an accumulation of soot in the folds of the scrotum. Pott is thus said to have been the first medical man to trace the cause of a cancer to an external agent, making soot become the first known carcinogen, and sooty warts the first known occupational cancer.

Pott did indeed publish a pamphlet in 1775 called Chirurgical Observations Relative to the Cataract, the Polypus of the Nose, the Cancer of the Scrotum, the different Kinds of Rupture, etc. But as Lynda Payne points out in her recent biography of Pott, while he did indeed make the correlation between soot and scrotal cancer, his treatise was about surgical treatment. It was not a call for social reform and better working conditions for the misused young boys who worked as sweeps. Accounts of Pott written in the century and a half after his death do not even mention his identification of sooty warts as an occupational disease. Only in the 20th century, as we began to deal with a variety of environmental carcinogens, was Pott rediscovered and hailed as the founder of the field. I suppose there is nothing wrong with looking for a historical hero in the battle against carcinogenic agents. But it is a distortion of Pott’s 43 years as a surgeon and teacher to treat that as his primary contribution to the medical arts.

Lynda Payne’s book, The Best Surgeon in England: Percival Pott, 1714-1788 (2017) presents an excellent account of what life was like in 18th-century London for both surgeons and patients. Dr. Payne was a faculty colleague of mine for many years at UMKC, and no one has a better understanding of the social side of medicine and surgery in early modern England. Plus, you can learn in the book about Percival’s exasperating son Bob, who squandered away large chunks of his father’s fortune, and who consorted with and later married the foremost courtesan of 1770’s London, Emily Warren, who was also painted by Joshua Reynolds as Thaïs (see it here). I am surprised the BBC hasn’t dramatized the saga of Bob and Emily. Or perhaps they have.

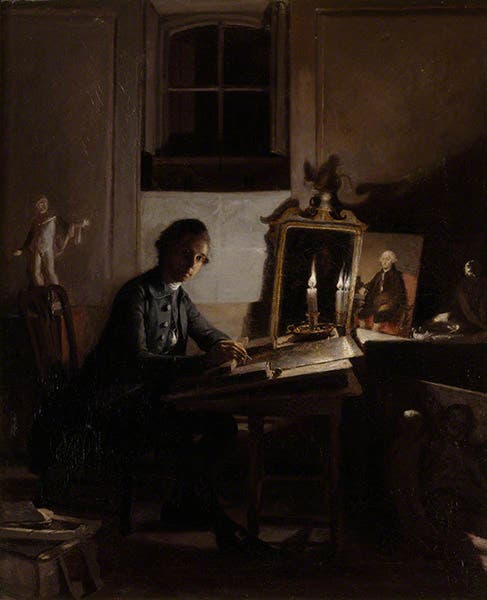

I thought I would leave you with one final painting, which intrigues me no end. It is not a portrait of Percival Pott, but a self-portrait of the artist, Richard Morton Paye; it was painted in 1783. Paye was a star-crossed artist of the late 18th-century, highly praised but ultimately unsuccessful in his career, for a variety of reasons. His painting of 1783 is called Self Portrait of the Artist Engraving a Portrait of Percival Pott (fourth image, above). You can see a small portrait of Pott (this one by Nathaniel Dance) on his desk. For some reason, Paye has taken a break from engraving Pott’s portrait, and is drawing himself. Many questions arise: why is he copying Pott’s portrait in the first place? Did Pott play some important role in his life? Why make it the occasion for a self-portrait? I have no answers for any of these. But I would love to be enlightened. And by the way, Paye wasn’t toying with us. He did complete an engraving of Percival Pott that same year, and you can see a print in the British Museum, which I link to here. It is a lackluster engraving. Perhaps that is why Paye turned to portraying himself.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![“Aurora Borealis,” hand-colored wood engraving by Josiah Wood Whymper, [Natural Phenomena], plate 2, 1846 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/0245ffcb-b70c-477c-8792-0a73ebd54eb2/Whymper%2011.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)