Scientist of the Day - Urbain Le Verrier

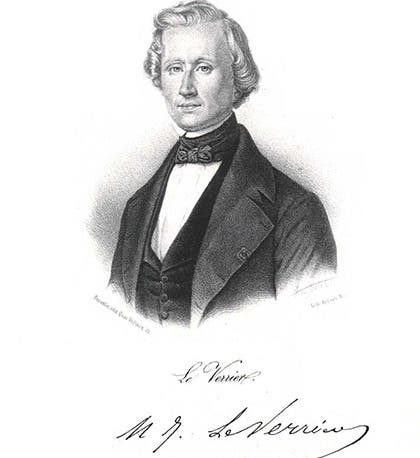

Urbain Le Verrier, a French astronomer, was born Mar. 11, 1811. His fame today rests primarily on his successful prediction of the location on an eighth solar planet, now called Neptune. The seventh planet, Uranus, had been discovered telescopically in 1781 by William Herschel. Over the next 50 years, as astronomers made new observations of Uranus and recovered some earlier unacknowledged sightings, they were able to work out its orbit with some precision, and it came to be realized that Uranus was not behaving as it should, if Newtonian mechanics were to be trusted. Up until 1830, Uranus moved a little faster than it should, and after that, it appeared to be moving too slow.

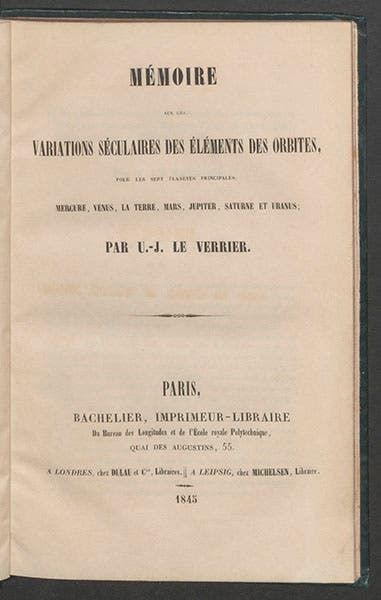

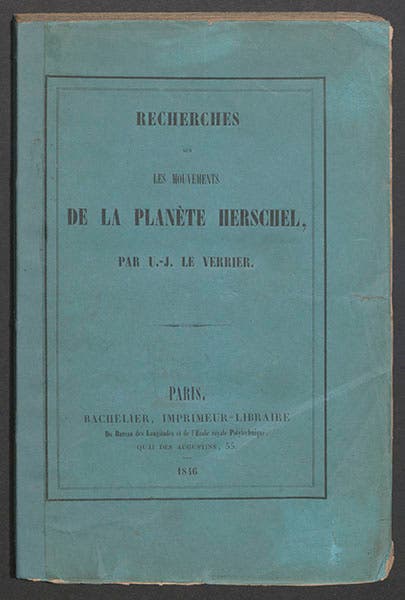

The Library’s two Le Verrier publications on planetary perturbations, 1845-46; see the captions to images three and four for the full titles (Linda Hall Library)

Several astronomers realized that the “perturbations” of Uranus, as the irregularities were called, might be the result of an unknown eighth planet, further out, that was exerting a force on Uranus. But hardly anyone thought that one could reverse-calculate the mass and location of a perturbing planet based just upon the wobbles of Uranus. The exception was Le Verrier, who thought it was possible, and proceeded to do so. He first published a small book on the perturbations of the seven known planets, to hone his mathematical skills (second and third images). By the summer of 1846, he had a prediction for an eighth planet – an area of sky to be scoured in search of a tiny disc that was not recorded on the stellar atlases used by astronomers.

Le Verrier, who was a 35-year-old assistant at the Paris Observatory at the time, could not generate much interest in a search from his superiors – no one apparently had much confidence in his predictions – so Le Verrier sent his prediction to Johann Galle at the Berlin Observatory. On Sept 23, 1846, the very day he received Le Verrier’s letter, Galle turned the Observatory’s Fraunhofer refractor on the designated area near the ecliptic in Gemini, and there it was, a tiny green disc that was not on the star chart. The new planet had been detected, close to where Le Verrier said it should be. The discovery of Neptune was a much more sensational event than that of Uranus, which was more or less accidental (Herschel took umbrage at this “accidental” label, since it slighted his skill as an observer, but the fact was, he was not looking for a new planet when he spotted Uranus). Neptune had been predicted, by someone wielding only mathematical skills and Newton’s and Laplace’s laws of celestial mechanics. Theory had guided observation, to the delight of therorists everywhere.

The British Astronomer Royal George Airy quickly pointed out that an Englishman, John Couch Adams, had made a similar kind of prediction of an eighth planet even before Le Verrier, and he took the blame for not acting on Adams’ prediction. For a century and a half, Adams was usually considered to be a co-discoverer of Neptune. Recent research, however, has shown that Adams’ predictions were not nearly as accurate Airy had indicated, and that Le Verrier probably deserves more than half-credit for the planet’s discovery.

The naming of Neptune was not straight-forward. Le Verrier wanted it named after himself and conspired with a colleague to put forward just such a proposal. Le Verrier even published a book in 1846 about Uranus, in which he renamed the planet, calling it Herschel right on the cover, as if to have a precedent for planet Le Verrier (fourth image). But German astronomers would have none of this, and before long, Neptune was the accepted name. Le Verrier went on to become director of the Paris Observatory in 1854, and by most accounts he was the most tyrannical, egotistical, ungracious observatory director the world has ever seen. He was eventually fired from the position in 1870, after a near mutiny by the senior astronomical staff. But when you have done something as magnificent as predict the existence of a distant object no one has ever seen, using mathematical tools that only you could wield, then they can never take that away from you, no matter how detestable your later life might have been. We pulled those two adjectives, magnificent and detestable, from the title of a recent biography of of Le Verrier. Not many scientists can acquire the second descriptor and retain the first.

Le Verrier eventually got his job back and died in office in 1877. He was buried in Montparnasse cemetery in Paris (fifth image), joining Gaspard-Gustav de Coriolis and Charles Joseph Minard. In 1889, a statue sculpted by Michel Antoine Chapu was placed in front of the Observatory, where it still stands (sixth image). It is rather amazing that it was erected at all, at least at that location. Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.