Scientist of the Day - Wyville Thomson

Wyville Thomson, a Scottish marine biologist, was born Mar. 5, 1830. Thomson is best known for coming up with the idea for the Challenger expedition (1872-76) and for participating on that epochal voyage as chief scientist. But since we featured the Challenger expedition not long ago, when we wrote a piece about Thomson's assistant, John Murray, we thought today we would feature the voyages of HMS Lightning in 1868 and HMS Porcupine in 1869, which Thomson led, and through which he probed the benthic regions of the North Atlantic and the Mediterranean.

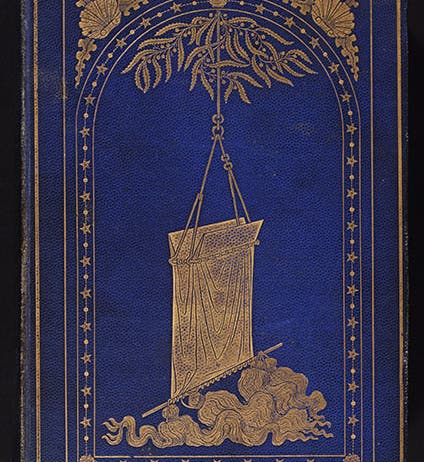

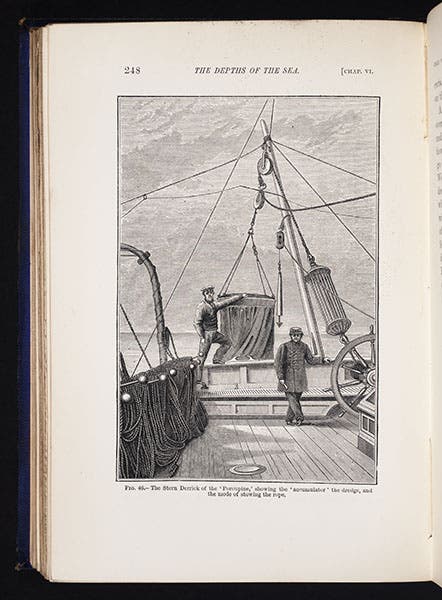

The prevailing opinion in the 1860s was that the deep sea, below about 500 feet, is bereft of life. Using a variety of dredges and winches, Thomson and the crews of the Lightning and Porcupine pulled up marine life from depths of several thousand feet. They also made hundreds of soundings and measured the ocean temperatures at a variety of depths. After he returned, and while organizing the Challenger expedition, Thomson published The Depths of the Sea (1873), which we have in our collections, and which is liberally illustrated, starting with the gold-embossed cover that shows a dredge being hauled on deck (first image). We get a better view of a dredge in one of the full page plates (second image), where we also see the store of rope that had to be carefully coiled so it could run out to 2500 feet, and on the right, an "accumulator," a shock absorber made of rubber cords that prevented the rope from snapping if the dredge got caught.

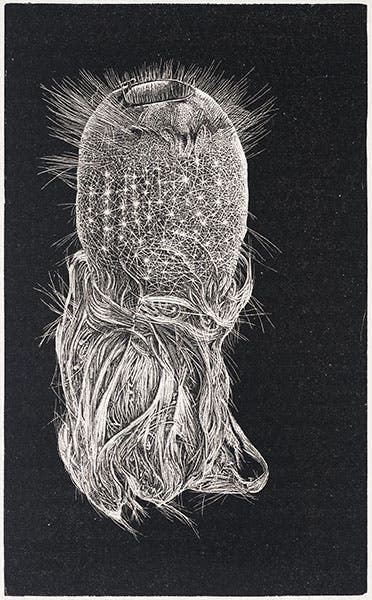

Thomas was especially interested in sponges and crinoids. One of the wood engravings in The Depths of the Sea shows a beautiful sponge, Histenia carpenteri, that Thomson discovered on the voyages and named after an assistant, W.B. Carpenter (third image).

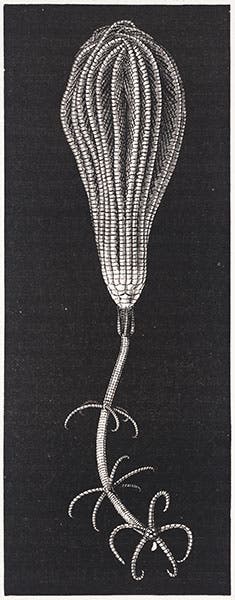

Another depicts a crinoid that was discovered by J. Gwyn Jeffreys, another assistant, who named his new find after his boss, Pentacrinus wyville-thomsoni (fourth image).

To the non-marine biologist, some of the more delightful features of Thomson’s book are the tailpieces that close each chapter, and which recall those of marine biologist Edward Forbes (who was also the one responsible for declaring the deep-ocean floor devoid of life). We show here a vignette depicting the “Giant and the Hag”, a rock formation in the Faroe Islands that was visited on the voyages of 1868-69 (fifth image).

After he returned from the Challenger expedition in 1876, Thomson found himself responsible for editing the voyage publications, and the enormity of the task (eventually 50 large volumes would be published) broke him down. He had to turn the editing responsibilities over to John Murray, found himself unable to teach again, and died in 1882. A bust in his honor still stands at the University of Edinburgh (sixth image).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.