Scientist of the Day - Adolphe Godin de Lépinay

Adolphe Godin de Lépinay, a French civil engineer, was born Oct. 10, 1821. He trained at the best engineering schools in France, and spent much of his career laying out railroads throughout Europe, including Algeria, designing some bridges, and he was apparently highly respected in his field. But today, we are going to focus on his role in the French Panama Canal project. This was organized by Ferdinand de Lesseps, who was fresh from the successful completion of the Suez Canal (1869) and looking for new worlds to conquer (and investors to attract). He settled on trying to bridge the Isthmus of Panama with an ocean-to-ocean canal. To that end, in 1879, he organized a conference, the Congrès international d'ètudes du canal interocéanique (International Congress for the Study of an Interoceanic Canal). Hundreds of engineers were invited, and just as many prospective financiers, and the stated purpose of the conference was to see if building a canal was feasible and if so, how best to build it. The big obstacle was the continental divide that runs right down through Central America, including Panama. A canal would have to cross it somehow, or cut through it.

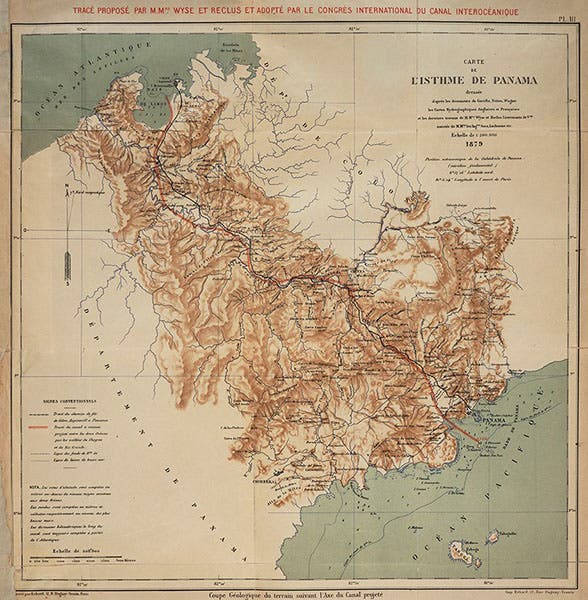

Building the Suez Canal had been simple in principle; since everything was more or less at sea level, you just had to dig a long ditch using heavy construction equipment. It was a lot of work, being 120 miles long, but straightforward and uncomplicated. But Panama was crossed from north to south by a mountainous ridge that reached some 300 feet above sea level. If you tried to build a sea-level canal, even though it would only be 50 miles long, there was an immense amount of earth to be moved, under tropical conditions far more dangerous than the situation at Suez. If you used locks on either end, that made things more complex, but you might raise the canal some 80-100 feet and save a lot of digging. We show a map, prepared in 1879 for the Congress (first image).

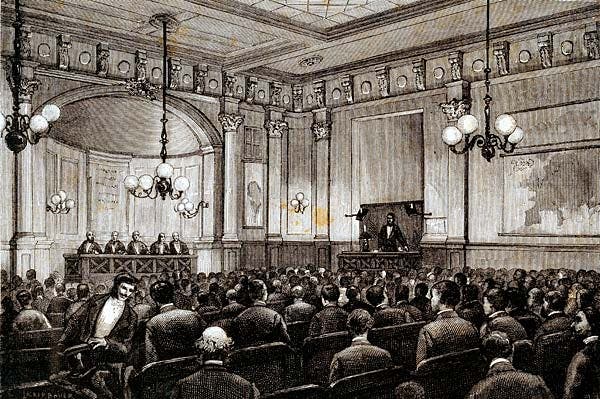

Enter Godin de Lépinay, who was invited to the Congress, which met in Paris in the great hall of the Geographical Society of France (third image). Godin de Lépinay gave considerable thought to the various possibilities, and he came to the conclusion that the only way to successfully build a canal in the designated time-frame (6 years), was to use locks to raise the canal some 80 feet, and then to build two dams to create two large lakes at the 80-foot level. These dams would control flooding of the Chagres and Rio Grande rivers, and the lakes would allow easy passage from one end to the other. Godin de Lépinay pointed out that the area was swampy and rife with tropical diseases, such as malaria and yellow fever, which would make working conditions nearly impossible, and that therefore speed was of the essence, for if the project dragged on too long, the impact on the work force might be catastrophic. Godin de Lépinay had worked in tropical countries – the only French engineer at the Congress who had – so he had first-hand experience with conditions like those in Panama. He submitted his proposal at the Congress.

Lesseps, however, was determined to have a sea-level canal, without the complication and expense of locks. It had worked at Suez, and it could be made to work in Panama. Godin de Lépinay's proposal was not so much rejected as ignored. The only purpose of the Congress, it turned out, was to get approval for the sea-level plan. Lesseps did not get it from the engineers, but he acted as if he had, and the project was underway, with construction begun by 1881.

The French Canal project was an utter debacle. Their machinery got mired in the muck, workers died right and left from disease, and after eight years, they had spent four times their budget and were not even a quarter of the way done. Investors pulled out, and the project ceased in 1889. The French retreated from the canal site, leaving millions of dollars’ worth of equipment behind (fourth image). Lesseps was arrested and hauled into court for misrepresenting the project to stockholders. He was sentenced to prison, but never served his sentence, for he died shortly thereafter, a broken man. Had he listened to Godin de Lépinay, who knows what might have happened. We are entitled to wonder, because the plan Godin de Lépinay proposed was almost identical to the one undertaken in 1904 by the American Panama Canal project, with a nearly identical system of locks, and dams just where Godin de Lépinay planned to build them.

Godin is something of a hero among American civil engineers, the man who cried wolf, but he has never achieved the reputation he deserves in France. You can find only one portrait on the internet, with an odd blue tint, but it’s all we have (second image). Godin lived long enough to see the French project fail, but not to see the American one even begin. But he apparently did well from his other engineering ventures, for he owned a huge estate in France, complete with castle, and on his death, he bequeathed it to the French Academy of Science. I don't know what they use it for, but they are happy to flaunt it on their website, and I re-flaunt it here (fifth image).

In 2014, on the centennial of the completion of the Panama Canal by the U.S., our Library opened an exhibition, The Land Divided, the World United: Building the Panama Canal, displaying many rare Canal-related items that came to us from the Engineering Societies of New York when we acquired their Library in 1995. You can see the two sections on the French project here and here. I did not find a portrait of Godin de Lépinay in the A.B. Nichols collection. But there are some splendid maps and photos, one of which we have used here.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.