Scientist of the Day - Andrea Cesalpino

Andrea Cesalpino, an Italian physician, philosopher, and botanist, was born June 6, 1519, in Arezzo, Tuscany. Cesalpino was a staunch Aristotelian philosopher; indeed, his first major book was titled Quaestionum peripateticarum, peripatetic being one name for Aristotelian. Given that Cesalpino played a major role in the scientific revolution of the late 17th century, this is a bit of a surprise, since much of the work of Galileo and others consisted of throwing off the yoke of Aristotle. But Galileo was a physical scientist, and Aristotle’s physics did indeed need replacing. In the natural sciences, it was different. Aristotle was the greatest biologist of the ancient world, and had provided a taxonomic system for animals that was better than anything that Europeans came up with until John Ray in the 1690s. Aristotle had definite ideas about how to classify the natural world, and it mostly involved discerning the essences of things, so that they could be sorted out. Some animals have bones, some do not, so you can sort them into two groups. Of those with bones, some have two-part hearts, some have one-part hearts, giving further groups. Some breathe with gills, some with lungs – more groups. In this way you can eventually sort everything into genera and species. Aristotle did so.

But with plants, it was not so easy. What are the essential features of plants? Do we sort them by size? By their flowers? By their locales? By their uses? Aristotle threw up his hands and said it couldn’t be done, and left it to his disciple Theophrastus to divide planets into trees, shrubs, undershrubs, and herbs, and then further sort them according to their uses. The later Greek botanist Dioscorides, who was a physician, took medical use as the primary criteria for classification, and this emphasis on medical utility in classifying plants continued down to Cesalpinos’s time, as the many 16th-century herbals in our collection well demonstrate.

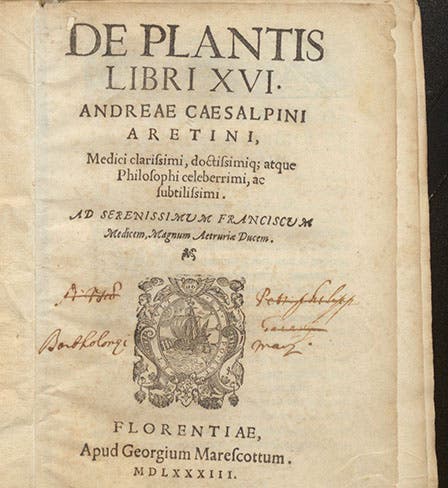

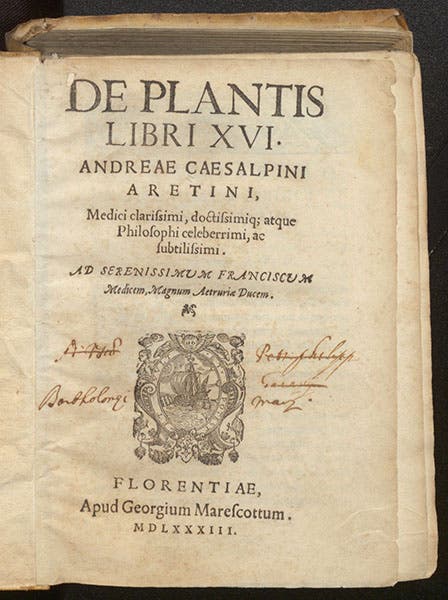

Cesalpino, in his De plantis of 1583, scrapped this entire approach and went back to Aristotle. Maybe we can figure out the essences of plants, he thought. After dividing them into two groups, woody and herbaceous, he then searched for the next set of taxonomic criteria, and settled on the “fructifying parts,” the structure of flowers, fruits, and seeds. This provided the basis for what Cesalpino called a “natural system,” one that organizes plants the same way nature has. It provided a completely different basis for plant taxonomy, with no attention whatsoever paid to use, medical or culinary. Cesalpino studied and classified hundreds of plants, showing a great eye for detail, in an era before microscopes. As if to emphasize the difference between his system and that of the herbals, De plantis has not one image in it. Which is perhaps why no one much looked at it for the next 80 years.

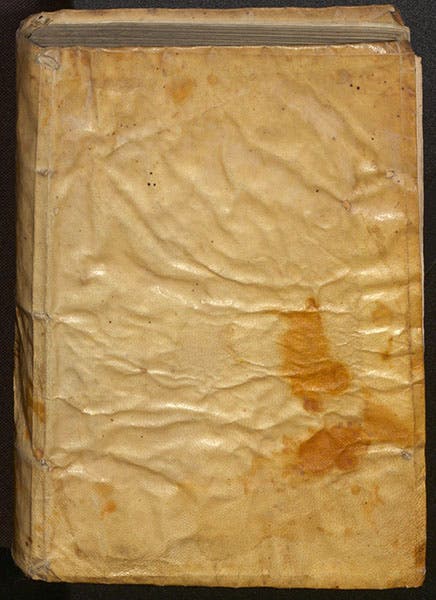

But in the 1660s, John Ray re-discovered Cesalpino and his natural system, and made it the basis for his own. Cesalpino in his book had defined a species as a collection of organisms that are mutually self-reproducing, and Ray adopted that as well. Carl von Linné (Linnaeus) in the 1730s also followed Cesalpino, calling him the father of botany, and agreed that the fructifying parts should be the basis for any system of plant taxonomy, including his own. De plantis ended up being one of the most important and influential natural history books of the late Renaissance. We have a lovely copy, in limp wrinkled vellum, in our History of Science Collection (third image).

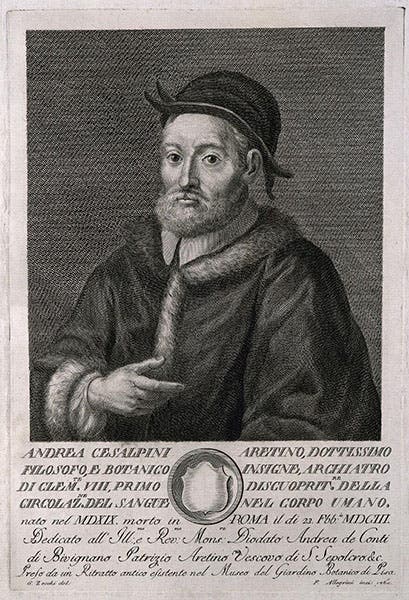

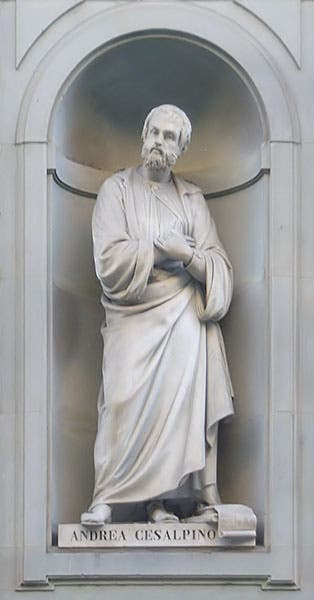

There is an oil portrait of Cesalpino at the Museo Galileo in Florence, but it looks suspiciously 19th century to me. The Wellcome Collecton in London has an engraving that appears to be more authentic, even if it is not contemporary, which we use for our portrait (second image). There is also a statue of Cesalpino in the loggia that underlies the Uffizi in Florence, where he properly joins Leonardo da Vinci, Galileo Galilei, and Francesco Redi as one of the most significant figures of early modern science (fourth image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.