Scientist of the Day - Andrew J. Russell

Andrew Joseph Russell, an American artist and photographer, was born Mar. 20, 1829, in Walpole, New Hampshire, and grew up in Nunda, New York, where he showed early talent as an artist. Russell learned photography in the Union Army in the early years of the Civil War, and took hundreds of photographs that are quite well thought of by those who study the imagery of the Civil War. But we are going to focus here on two post-war years, 1868-69, when Russell worked for the Union Pacific Railroad and helped document their progress across the plains and the Rockies to meet the Central Pacific coming east, in order to complete a transcontinental railroad.

Photographers in the 1860s used the wet collodion process, where a glass plate was coated with collodion, a syrupy emulsion, then with silver nitrate, and placed in a large-format camera and then exposed. The plate had to be developed within the hour. So a documentary photographer like Russell had to haul around a 30-pound camera, scores of glass plates, and a portable developing tent, usually mounted on a small horse-drawn wagon. Crossing the Rockies with such equipment is hard to imagine, but that is what Russell did, and he took memorable photographs all the way.

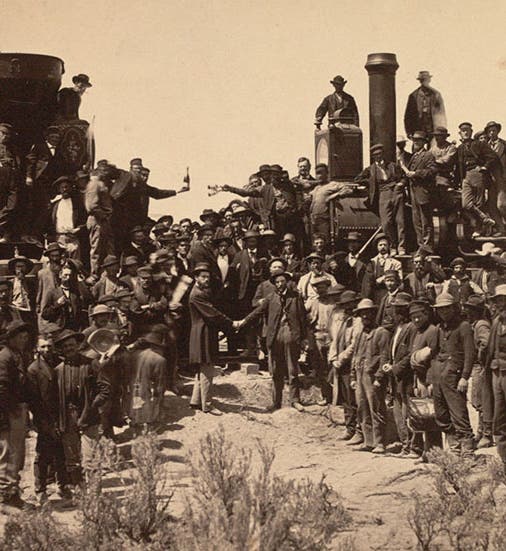

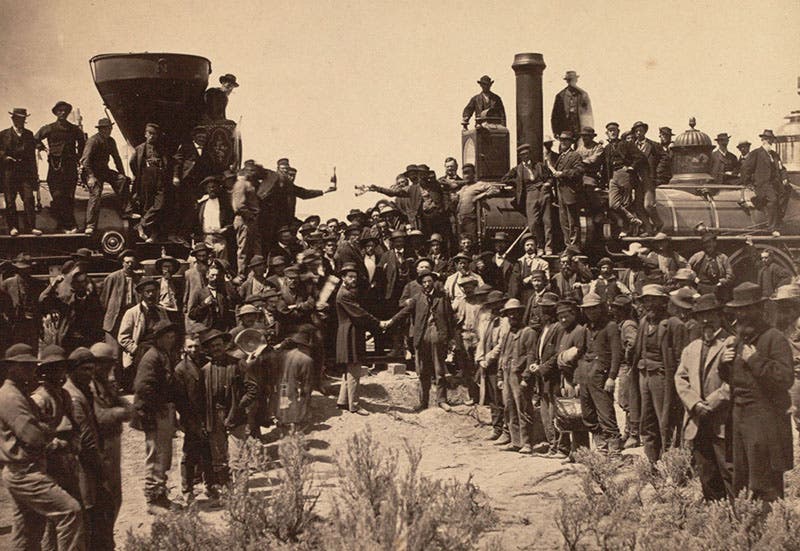

His most recognizable photograph is the one we placed first, because, well, it deserves to be first. It records the celebration on May 10, 1869, after the “Driving of the Golden Spike,” or the “Laying of the Last Rail,” as the event at Promontory Summitt, Utah, has been called, where the engines of the Union Pacific and Central Pacific came together, nose to nose.

There were three photographers present for the occasion, and many collodion plates were exposed, but this is the one that has become canonical. The presidents of the two respective railroads shake hands in the foreground, and a champagne toast is offered in the background. But Russell took many other photographs in his two years with the Union Pacific (two years broken up by frequent returns to New York City and his home in Nunda). These photographs are wonderfully composed, and they record not only the building of the Union Pacific, but the landscape of the American West, as it became populated with workers and settlers.

There are quite a few museums that have sizeable Andrew J. Russell photograph collections, such as the Library of Congress, the Beinecke Library at Yale, and the Oakland Museum of California. The Oakland Collection was the easiest to access online, and so I went through all 650 of their thumbnails and chose my favorites, skipping those that were from the Civil-War era. The ones I selected show a famous trestle bridge at Dale Creek, Wyoming (third image); another completed bridge at Green River, Wyoming (fourth image); and still another bridge, this one under construction, also spanning the Green River (fifth image). You will note that this last one is a stereophotograph, two photos taken simultaneously with a single camera, the print from which can be viewed in a stereo viewer, to produce a three-dimensional effect. Stereocards were very popular in the last half of the 19th century, and Russell took hundreds of them.

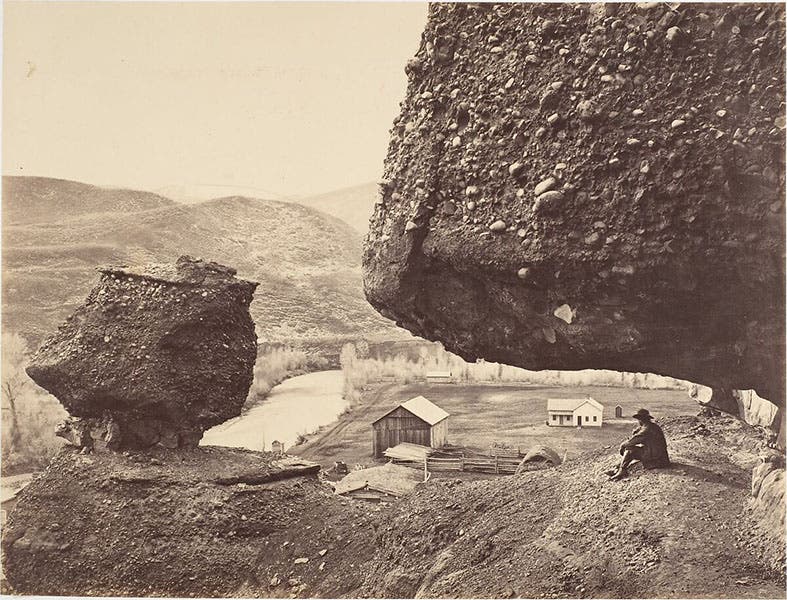

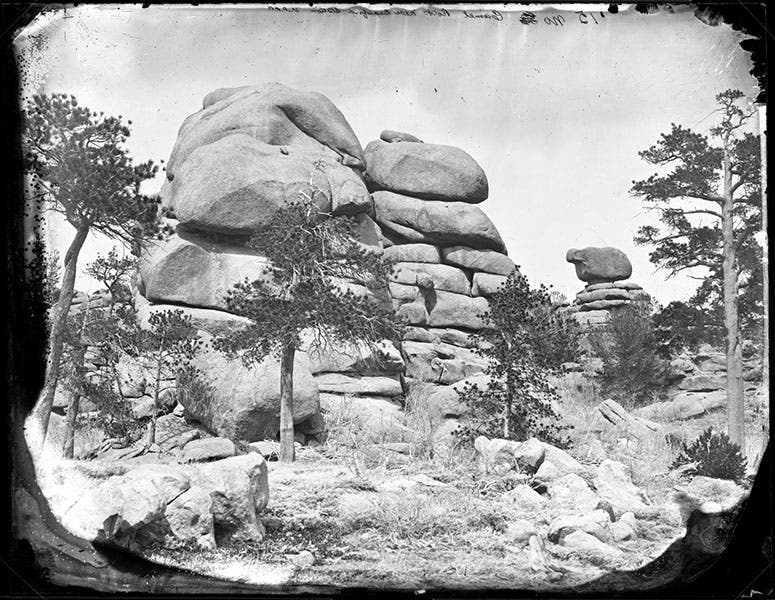

Many of Russell’s photographs capture the glorious landscape of the West, usually with people included to provide a sense of scale. “Hanging Rock at the Foot of Echo Canyon, Utah,” is one of Russell’s most often reproduced landscape photos, and it is easy to see why (sixth image). “Smith’s Rock, Green River, Wyoming” is also popular (seventh image). However, I have never seen our last image reproduced anywhere. Scratched on the plate is the label: “Camel Rock near Beauford Station,” and it records some unknown location, perhaps in Wyoming. I really like it, perhaps because it functions as a compact essay on Western geology.

Russell’s days with the Union Pacific ended abruptly on May 10, 1869, and he then travelled west, exposing plates all the way to California. To earn a living, he sold his photographs, individually and in collections, and they were fairly popular and earned him a decent income. In 1870, a book was published with the cumbersome title: Sun Pictures of Rocky Mountain Scenery, with a Description of the Geographical and Geological Features, and Some Account of the Resources of the Great West; Containing Thirty Photographic Views along the Line of the Pacific Rail Road, from Omaha to Sacramento. The book is attributed to Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden, but in fact, the 30 photos were all taken by Russell. We have this book in our collections, but for some reason, Russell’s role as photographer is not recorded in the catalog record of the book (which we acquired from the Engineering Societies Libraries). As soon as we get this straightened out, and can scan the book, we might write a second post on the one Russell book in our collections.

I was greatly aided in writing this post by the well-written and richly illustrated book, Across the Continent: The Union Pacific Photographs of Andrew J. Russell, by David Davis (University of Utah Press, 2018), which our library has in its collections. The book (p. 31) reproduces a better and larger version of the tintype portrait of Russell that we show as our second image, which is supposed to be in the Oakland Museum, but I could not find it there. If I ever do run it down, I will replace our portrait with the better one, and remove these last few sentences.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.