Scientist of the Day - Arthur Koestler

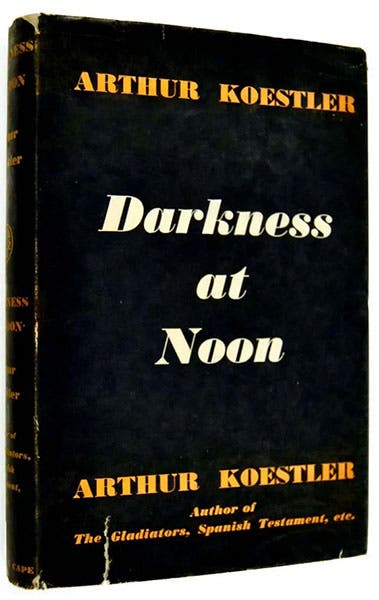

Arthur Koestler, a Hungarian-British writer, died Mar. 1, 1983, at the age of 77. Born in Budapest, Koestler had an extraordinarily turbulent life, at least until after the Second World War. He spent several impoverished years in Palestine in the late 1920s, until his freelance reports attracted attention, and he was picked up as a journalist by a Berlin newspaper consortium. In the mid-1930s, he was in Spain as a correspondent, when he was arrested by Franco's troops, imprisoned, and almost executed. In 1938, while in France, he wrote Darkness at Noon, in German; it was smuggled to England by his current lover, who translated the novel and arranged for its English publication. Koestler escaped France before the German occupation and eventually just showed up in England, with no permits, and was imprisoned. When Darkness at Noon was published in 1941 to great acclaim, he was released, and then served as a propaganda writer for the duration of the war. He lived primarily in England, with some time in France and the United States, for the duration of his life.

Koestler gets a nod as a Scientist of the Day because, in 1955, he began to write a biography of Johannes Kepler. Koestler had some training in science, and had served in the early 1930s as science editor to his Berlin newspaper. I don’t know when or how he first became interested in Kepler – I suppose I could read his multi-volume autobiography, but I have no interest in doing that, as there is a lot about Koestler that is not especially likable. But what drew Koestler to Kepler is obvious from the book he wrote. Kepler was this brilliant mathematician who discovered the three laws of planetary motion. But he had all sorts of physical problems – skin lesions, boils, piles – as well as a mother who was tried for witchcraft. He had this great desire to find harmony in the arrangement of the universe, but it always eluded him. He was half mystic and half empiricist, so his quest for harmony was continually dashed by facts that didn’t fit and which he refused to fudge. He spent years trying to remove tiny errors from his model for the orbit of Mars, errors that others would have ignored, and when he did finally succeed with an elliptical orbit, he did not realize what he had done, but tried to reproduce the ellipse with circles moving on circles. Every step Kepler took was, according to Koestler, blind and confused, and yet he managed to stumble his way to success after success. Koestler came to believe that this is how science progresses, like a drunkard’s walk, which eventually might succeed in getting somewhere, but hardly through a rational process.

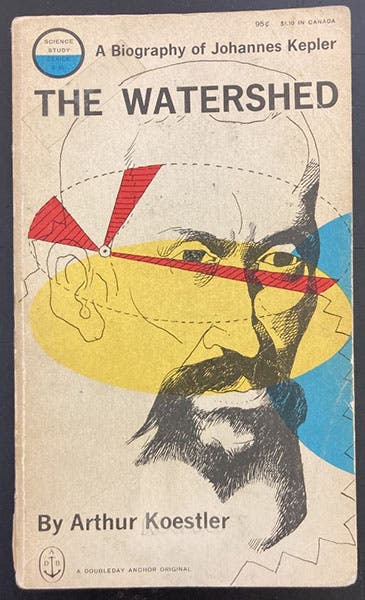

Front cover, The Watershed, by Arthur Koestler, first edition thus, Garden City, N.Y., Doubleday Anchor, 1960 (author’s copy)

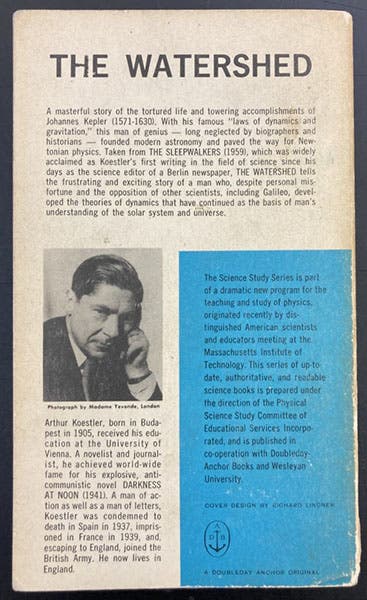

Somewhere along the line, Koestler decided to expand his biography of Keper into a triple-biography, bringing in Nicolaus Copernicus and Galileo Galilei. The completed book, written in English, was published in 1959 as The Sleepwalkers, the title reflecting Koestler’s belief that scientists just stumble along, not really knowing most of the time what they are doing. The section on Copernicus was harsh, as Koestler portrayed him as a fool, barely competent in astronomy, and Galileo emerged as a conniving and disingenuous manipulator. Historians of science, reviewing The Sleepwalkers, were not kind to Koestler and his take on the scientific revolution, even if Darkness at Noon was one of the great novels of the 20th century. But it was apparent to many that the section on Kepler was much more compelling than the rest of the book, and that part was reprinted separately, in 1960, as The Watershed, so titled because Kepler was portrayed as the bridge between Renaissance magic and 17th-century rationalism. The book was published in the new Science Study Series that was launched to bolster science education in the U.S. after the Soviets had beaten us into space in 1957 with Sputnik.

Back cover of The Watershed, by Arthur Koestler, 1960 with a description of the Science Study Series, (author’s copy)

I have a soft spot in my heart for The Watershed, with all its flaws. I had majored in physics in college but did not want to be a practicing scientist; flirted with law school for a year but remained unsmitten; and ended up in the U.S. Air Force as a flight line officer during the Vietnam war, when I chanced, on a midnight shift when nothing was happening, to read The Watershed, pretty much cover to cover in one sitting. I was enthralled. This was science made exciting, in a way that physics classes never had been. I still remember one sentence, describing the first encounter of Kepler with Tycho Brahe, who had lost his nose in a duel: “they met, face to face, silver nose to scabby cheek.” Wow! This was my first introduction to the history of science. I did not know that it was an inaccurate and biased book, and I wouldn’t have cared. I soon discovered that there were graduate programs in the history of science, applied to and was accepted by the University of Wisconsin in Madison, and, upon discharge from the service, I was off and running.

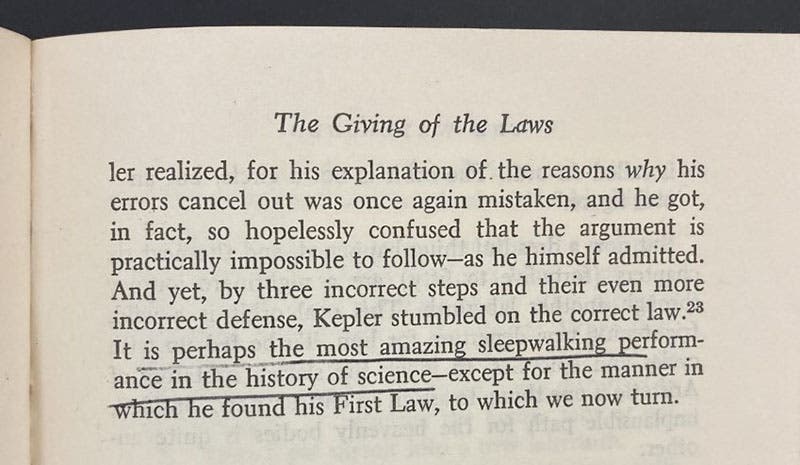

A page from The Watershed, by Arthur Koestler, 1960, describing Kepler as a sleepwalker (author’s copy)

I remember this experience because it made me realize, much later, that there is a place in our field for books by novelists and journalists who are not trained in our discipline. If a biography of a scientist is a gripping page-turner and gets people interested in the history of science, then it is doing something worthwhile, even it if is not always, or even sometimes, accurate. So when, after a public lecture, someone would come up to me, gushing that they have just read Daniel Boorstin’s The Discoverers (1983), or Bill Bryson’s A Short History of Nearly Everything (2003), two of the most error-filled history of science books ever written, and enthusing, “Wasn’t it wonderful!”, I would try to respond positively, with something like: “Yes. That is some book, I must say. Isn’t the history of science exciting?” And I owe this tolerance, foreign to my nature, entirely to Arthur Koestler’s The Watershed.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.