Scientist of the Day - Athanasius Kircher

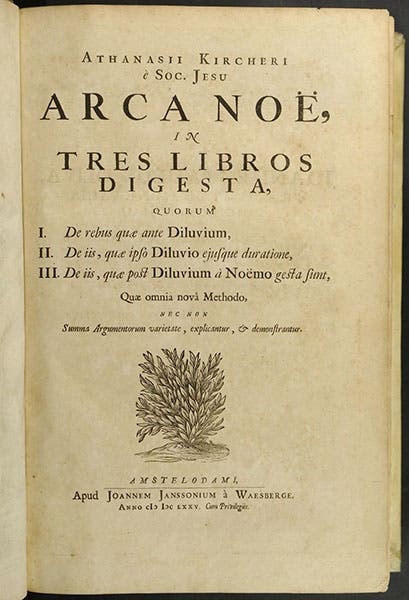

Athanasius Kircher, a German Jesuit natural philosopher working in Rome, was born May 2, 1601 (or 1602), in Fulda, Germany. Kircher was as prolific a scientist as could be found in the 17th century, writing some 40 compendia, most of them thick folios, on cosmology, optics, magnetism, geology, music, obelisks, and museums. We have published two posts on Kircher, in 2016 and in 2023, and we have many more to write. There is a portrait in both earlier posts, so we do not include one here. Today we present one of Kircher’s stranger works, his Arca Noë (The Ark of Noah, 1675), which tells us a great deal about Kircher's approach to the natural world, and to Scripture.

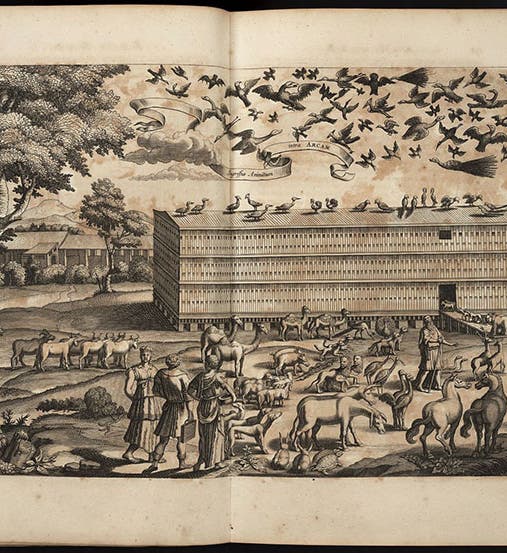

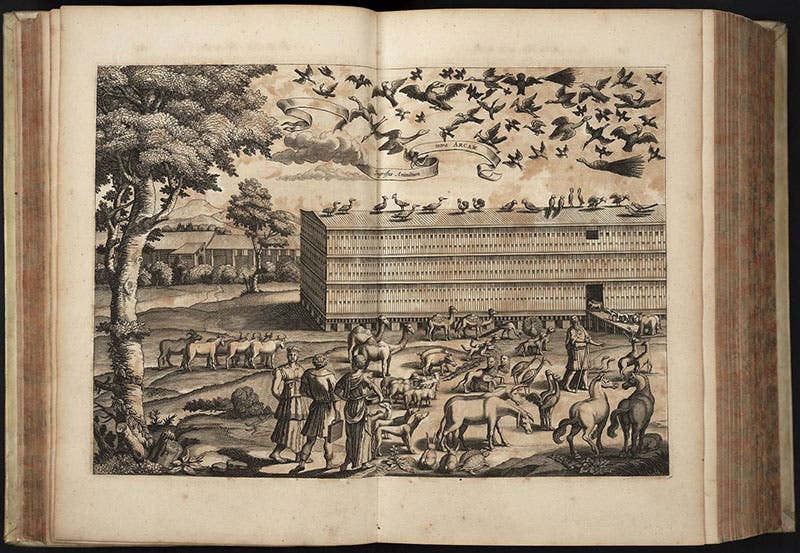

The Arca Noë is a thorough examination of Noah's Ark, its probable size and layout, how it must have been built, and provides a description of events before, during, and after the Great Flood. Before you smile too much, remember that nearly everyone living in the 17th century, including Isaac Newton, Francis Bacon, and Johannes Kepler, believed that the Old Testament was written by Moses, guided directly by God, and was literally true. Consequently, Noah was considered to be a real historical figure who lived to the age of 950 years, and who, in his 650th year, supervised the construction of an Ark, to save the part of the animal kingdom that needed saving, and a few humans (Noah's family), from a cataclysmic Flood, which was a real historical event. Genesis tells us a little about the Flood and Noah's role in it, but there is much omitted from the scriptural account. A smart fellow could figure out such things as what animals would have to have berths on the Ark, how big the Ark would have to be, how the compartments were probably laid out, what kind of provisions would have to be laded, and what actually happened as the waters began to rise. And if you were a member of a well-to-do order (such as the Society of Jesus) and had wealthy patrons, you could afford to illustrate your account of Noah's Ark with large copperplate engravings.

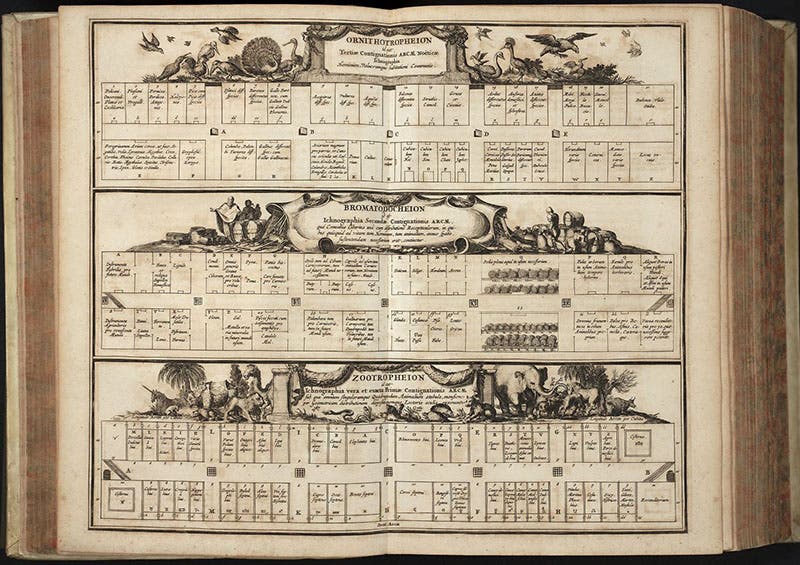

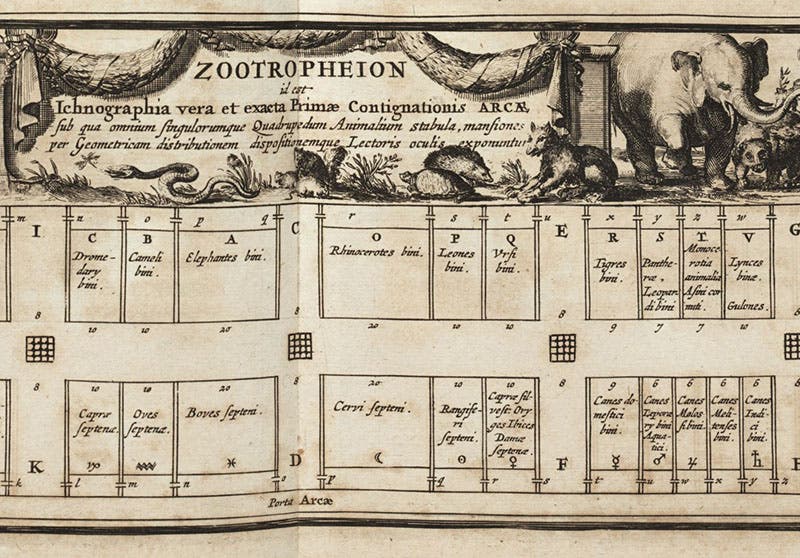

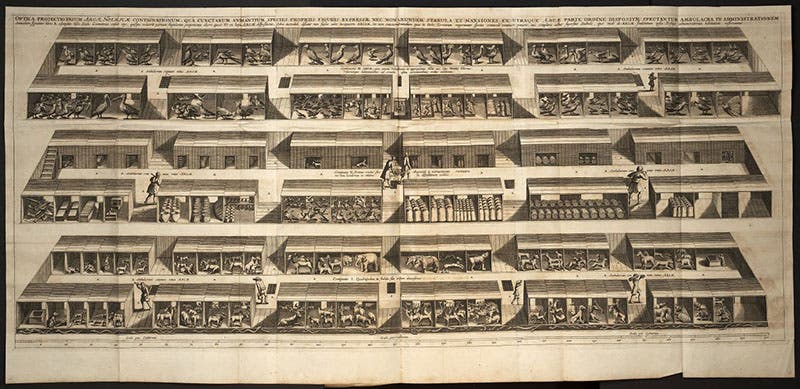

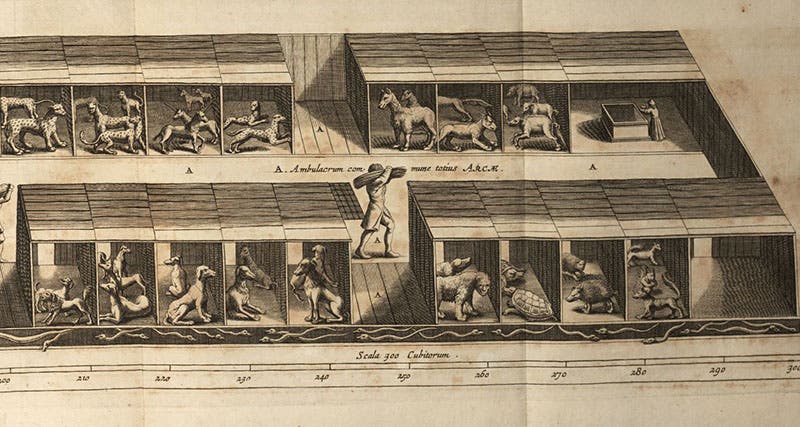

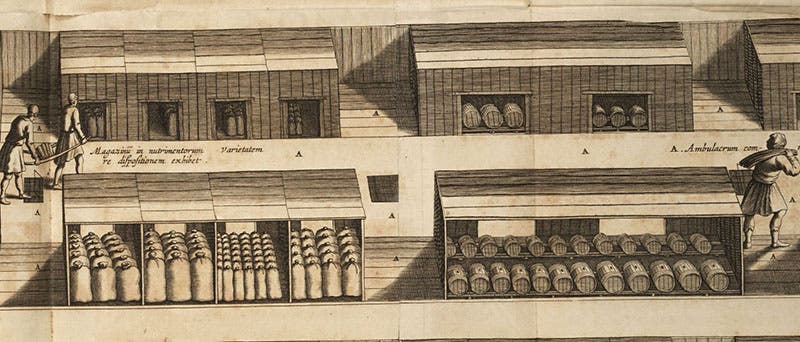

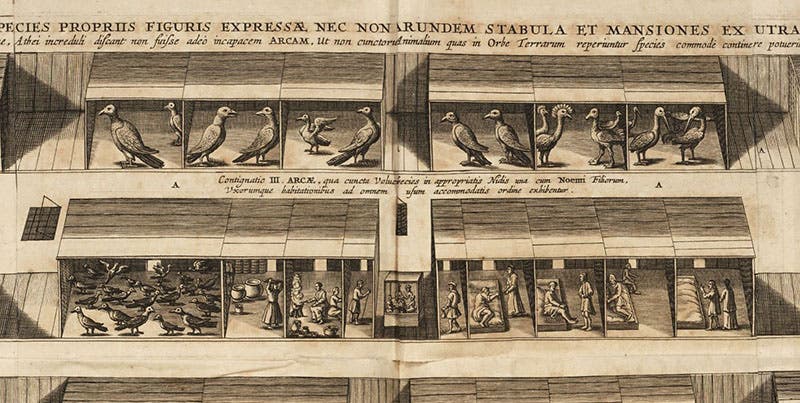

Kircher reasoned that, since the Ark was called a "chest" rather than a ship by Moses, it probably did not look like a boat, but was rectangular in shape, with multiple levels, most likely three - a bottom tier for animals, a middle level for stores and provisions, and a top tier for birds and the few humans on board. Turtles might need a ride, but all of the fish and most of the reptiles, amphibians, and water birds, could survive a few months in the water. Insects, it was thought, generated from mud and putrefaction, and there would be plenty of that around when the waters subsided. So there were no insects on board , except for those like fleas who hitched a ride.

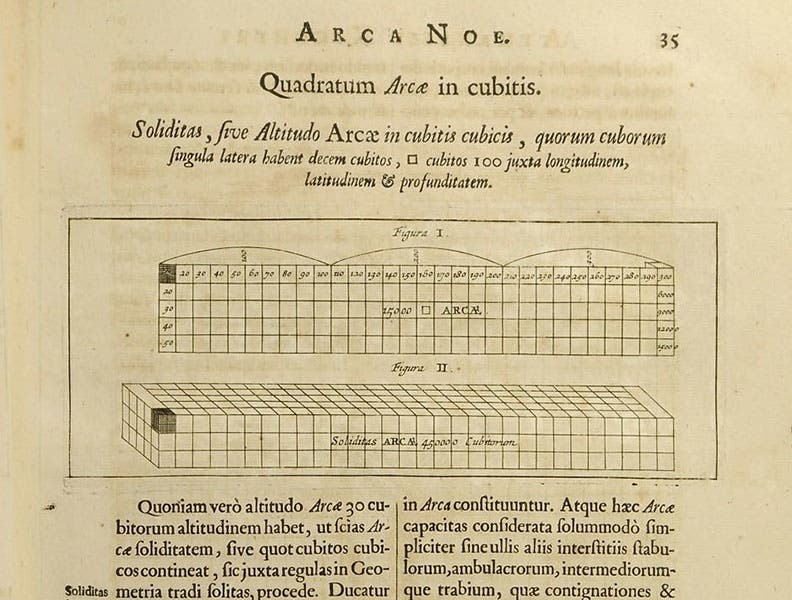

There were not that many species known in the 17th century – a few hundred mammals and a few hundred birds – and while a pair of elephants or rhinos required large compartments, most of the smaller animals did not need much space. Kircher calculated that 450,000 cubic cubits (a cubit was 18 inches) would do the trick, 150,000 for each of the three levels. The crucial cargo was not the animals, but the supplies, for Moses and his three sons would need to restart the world after the Flood, which would require tools, ploughs, grain and seeds for planting, and much more. The entire middle tier of The Ark would have to be devoted to such stores.

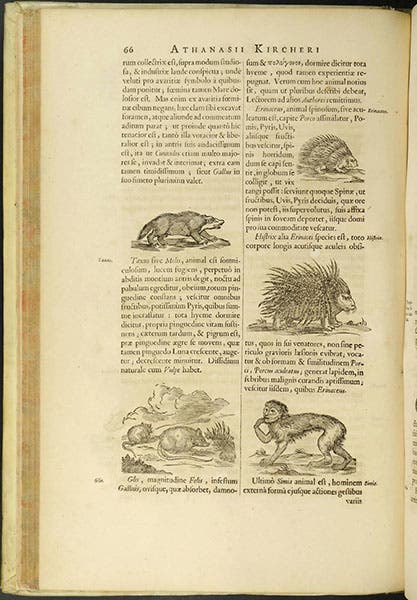

The most charming part of Arca Noë are the double-page engravings, which show the building of the Ark (third image), the loading of the animals (first image), an "ichnographic" plan that shows who went where (fifth and sixth images), and an "optical projection" that presents all three levels, filled with animals, birds, and supplies (seventh - tenth images). The detail is so rich that an in-person reader of the book can hardly make out the details, so I have provided several zoomed-in views. I wish I had room for more.

The Arca Noë is essentially a book on naval architecture and engineering, which I suppose qualifies it for a science library. But its real merit for inclusion is contained in a long section on the occupants, with discussions and woodcuts of lions and bee-eaters, hippos and hoopoes, which makes it a legitimate work of natural history. I show only one of these pages (the engravings are much more interesting), one that includes our library mascot, the hedgehog. Thank you, Noah; our hedgehog is a direct descendant of yours.

There is much more in the book that can enthrall the modern reader. Kircher calculated how much water it would take to cover the Earth to the level of the highest mountains, and concluded that so much water could never have been supplied by rain or subterranean seas, so the event was truly miraculous. He deduced that Noah and his sons must have lived for decades, after the Flood, near the top of Mount Ararat, where the Ark came to rest, because the valleys below would have been filled with death and decay. He even provided a lovely engraving of the Tree of Adam, a literal tree, with Adam and “Eva” at the base of the trunk, and Noah about halfway up (and Abram at the top-most twig). I wish I had room to show it and several more, but I am already way over my limit.

Finally, I would like to tip my hat to an old-fashioned intellectual historian, Don Cameron Allen, whose book, The Legend of Noah (1949), could never be written today, because it paid no heed to social context. It was a contribution to the history of ideas, a genre now out of fashion. But Allen included an appendix solely devoted to Kircher's Arca Noë, where he analyzed the book in great detail, indicating that Allen was one of the few historians of the last hundred years who actually read the entire book, and did so sympathetically. He paid no attention to the illustrations, which no one did back then, but he really dove into the Latin text, as no one had before (or since). I could not have written this post without Allen's wonderful book. And I am glad he left the images alone. It gives me something of my own to contribute.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.