Scientist of the Day - Augustus Earle

Augustus Earle, an itinerant English artist, died Dec. 10, 1838, at the approximate age of 45. Earle was the first of a new breed of painters – travel artists – who transported themselves incessantly by ship to the remote corners of the globe and made sketches as they went, collecting raw material for finished paintings that they might sell to a commercial market. Earle sailed to North and South America, Australia, Tristan da Cunha, Tasmania, Australia, and New Zealand, all before he was thirty. What made Earle different from previous ship's artists, such as Sydney Parkinson, who accompanied Captain Cook on his first voyage in 1769, is that ship's artists worked for the captain and were bound to the ship, while Earle simply used a ship as a means for getting from one place to another. Parkinson, for example, visited New Zealand with Cook and made some valuable drawings of the Maori, but when Cook left after a few weeks, Parkinson left too. Earle, on the other hand, lived in New Zealand for 9 months and got to know his subjects (the Maori) remarkably well.

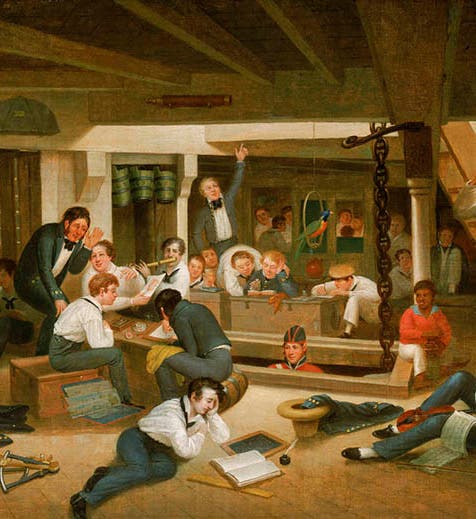

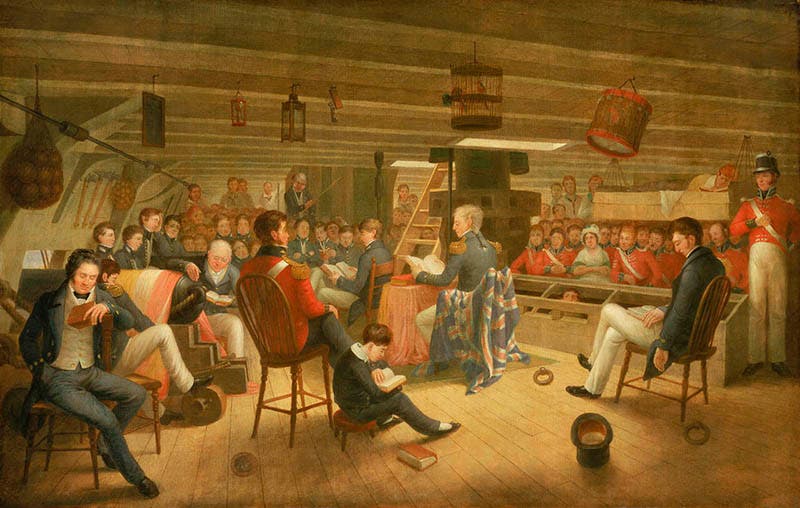

Earle also created a new kind of maritime art. The traditional maritime painting either showed ships at sea or in port, or depicted them engaged in fiery battles. Maritime art was heroic art. Earle made two oil paintings that he displayed at the Royal Academy of Art in 1837 and the activities they depict are far from heroic. The first painting is usually called Life on the Ocean (although I prefer Leisure Time) and depicts a group of midshipmen below deck of an admiralty vessel, engaged in a variety of quiet activities such as reading, writing, drawing, playing with pets, or making music. The other is traditionally called Divine Service at Sea, and shows a captain conducting a religious service aboard the same or a similar ship. It is thought that both paintings were based on sketches made while on board HMS Hyperion on a voyage to South America in 1820. Both works of art are in the National Maritime Museum at Greenwich.

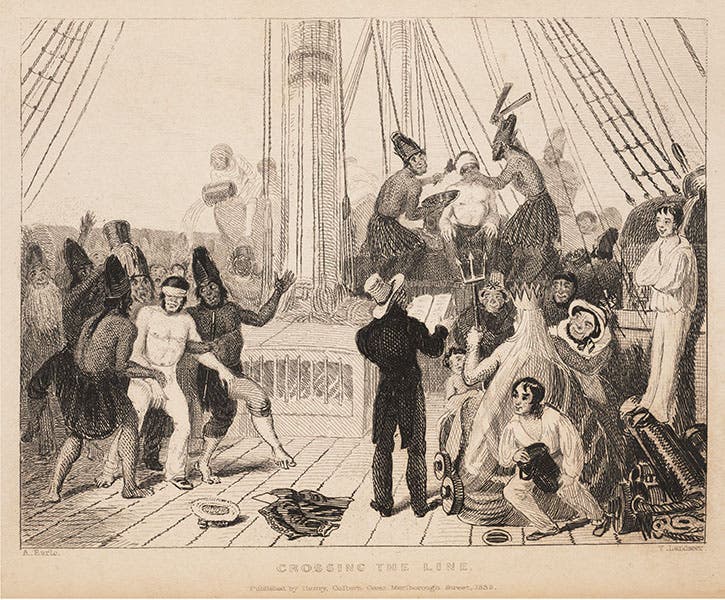

It is interesting that the one time that Earle accepted a position as ship's artist, he lasted less than 9 months. In hindsight, resigning his position might have been a big mistake, because the ship was HMS Beagle, the year was 1831, and a supernumerary passenger on board was Charles Darwin. It is usually said that Earle became sick and had to be put ashore in South America, and this may be true, but it is also possible that an artist who has gone his own way and sketched what he wanted for 15 years, might not have taken kindly to pictorial orders from Capt. Fitzroy. Nevertheless, at least six of Earle's Beagle sketches were made into prints for Fitzroy's Narrative of the Voyage of the Beagle (1839), which we have in our collections. We show here Earle’s version of "Crossing the Line," depicting the indignities that newbies (including Darwin) had to endure when crossing the equator for the first time, and link to another that shows the port of San Salvador, Bahia, where the Beagle docked.

The voyage of the Beagle was 11 years after the voyage of the Hyperion, but since the two maritime oils were not displayed until 1837, some scholars have speculated that perhaps Life on the Ocean and Divine Service might contain elements drawn from the Beagle and her crew. In particular, it has been suggested several times that the studious gentleman in the left foreground of Divine Service, engrossed in his own book while the captain reads from the Bible, might be Charles Darwin himself. It is a tantalizing proposal.

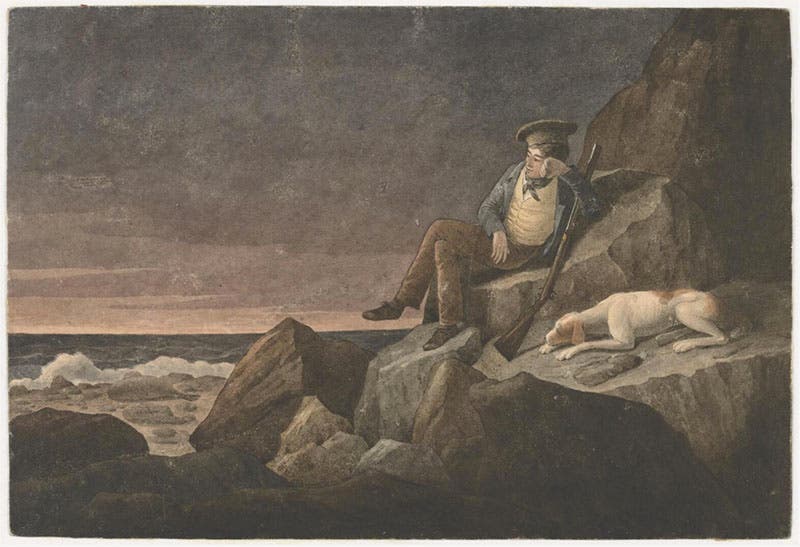

There is one known self-portrait by and of Earle, made at Tristan da Cunha in 1824; it is in the National Library of Australia. Earle’s ship had stopped at the remote island in the middle of the South Atlantic and then inexplicably sailed off without Earle, leaving him to wait 8 months for another ship to come calling. Earle should have realized, then and there, that there are some advantages to having an official position as ship’s artist, for a vessel seldom leaves behind a member of its own crew. Perhaps that experience is what prompted him to sign on with HMS Beagle in 1831.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.