Scientist of the Day - Barthélemy Faujas-de-Saint-Fond

Barthélemy Faujas-de-Saint-Fond, a French geologist, paleontologist, and scientific traveler, was born May 17, 1741. We wrote a post on Faujas one year ago, and another three years before that, and we are not close to exhausting the extent of his scientific achievements. Our first post discussed his involvement with the first launches of hot-air balloons by the Montgolfier brothers in 1783. Our second post looked at Faujas' book on the "monster of Maastricht," a large fossil skull dug out of Mount Saint Peter in Maastricht that would later be named a mosasaur by Georges Cuvie

Today, we look at the first book of Faujas-de-Saint-Fond, quite a show-stopper for a debut publication. It was called: Recherches sur les volcans éteints du Vivarais et du Velay, published in 1778, which translates to: Research on the extinct volcanoes of the Vivarais and the Velay. In 1771, Nicolas Desmarest had surprised the geologists of France when he pointed out that the mountains of south-central France, in the region known as the Auvergne, are actually extinct volcanoes, and that the prismatic basalt that overlies much of the surface had emerged long ago as molten rock from those volcanoes. The consensus before Desmarest was that basalt is a sedimentary rock, deposited under water. The realization that basalt is an igneous rock, and that (since basalt is a common rock world-wide) volcanoes were once much more prevalent and may have played an important role in shaping the Earth's surface, would cause quite an upheaval in geological thought over the next fifty years.

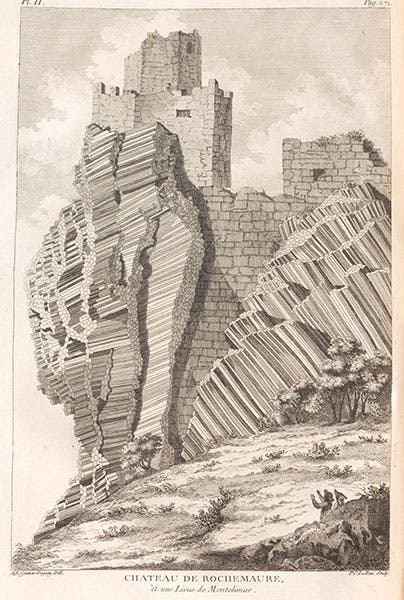

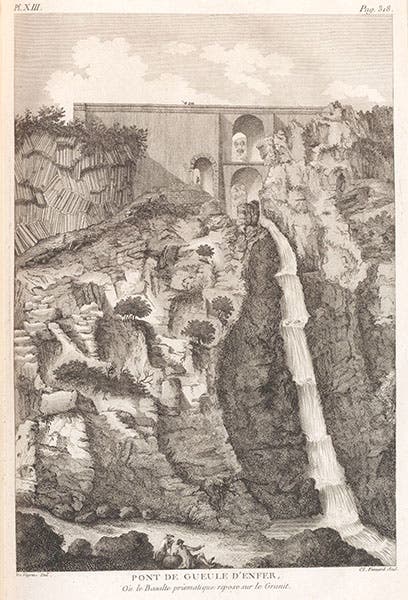

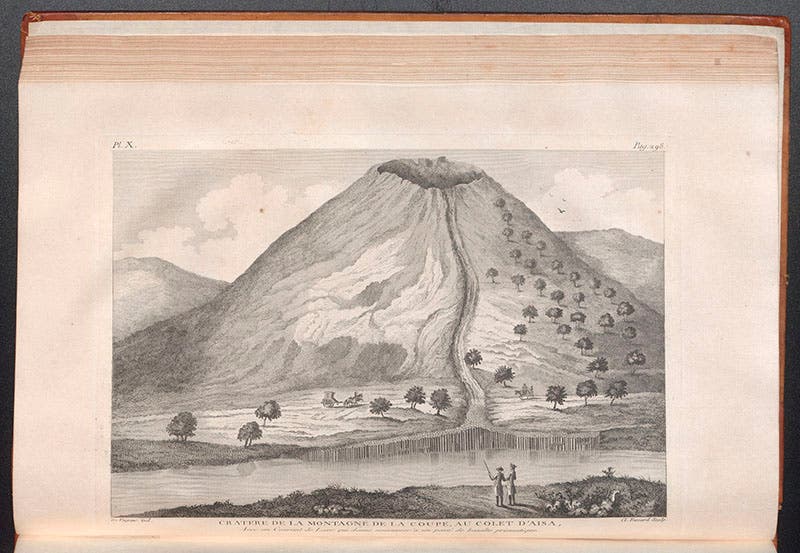

Faujas' 1778 book was an attempt to extend Desmarest's conclusions to other areas, in particular, to the Vivarais and the Velay, in southeastern France. Both are mountainous (and picturesque), and strewn with basalt. Faujas depicted many of these basalt-rich areas with full-page engravings that are just magnificent. We show you here the baby giant’s causeway at the Bridge of Bridon (first image), the wonderful Chateau de Montélimar (third image, above), and the Bridge of Gueule d'Enfer (fourth image, just above), where basalt sits directly atop granite bedrock, as Faujas points out in his caption. He even found a mountain with a crater for a summit, in which there was a cut, and a lava trail that leads directly to prismatic basalt at the base (fifth image, below). It is hard to find better evidence than this for the volcanic origin of basalt.

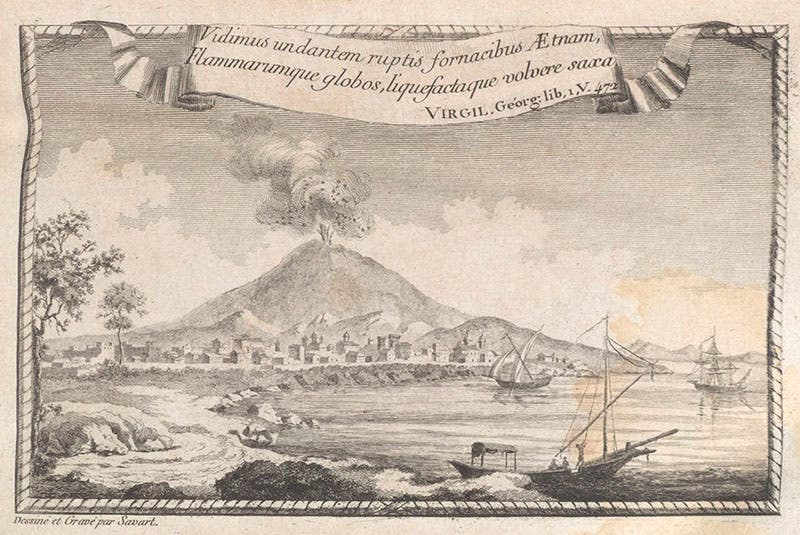

We have talked on several occasions in these posts about headpieces, the engraved vignettes that often introduced text segments in 17th- and 18th-century books (most recently in our post on Pierre Varignon). I am not sure how much we have discussed title-page vignettes, which were equally popular, especially in large folios like this one, where there was plenty of room on the title page for an engraving. Not only do these engravings make the title page more attractive, but they allow for a little classical learning to show through. In this case, the vignette portrays an active volcano, with a quotation from Virgil: "How often have we seen the furnaces of Mount Etna rupture and throw up flaming globes and molten rock." We show here both the full title page (sixth image, above) and a detail of the vignette (seventh image, below).

At some undetermined future date, we will offer one most post on Faujas-de-Saint-Fond, where we will discuss his trip to the Hebrides and Scotland in the 1780s, when he introduced young James Smithson (of future Smithsonian Institution fame) to the rewards of field geology, and also dropped in on William and Caroline Herschel, to provide us with our only account of how brother and sister went about the nightly practice of observational astronomy.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.