Scientist of the Day - Barthélemy Faujas-de-Saint-Fond

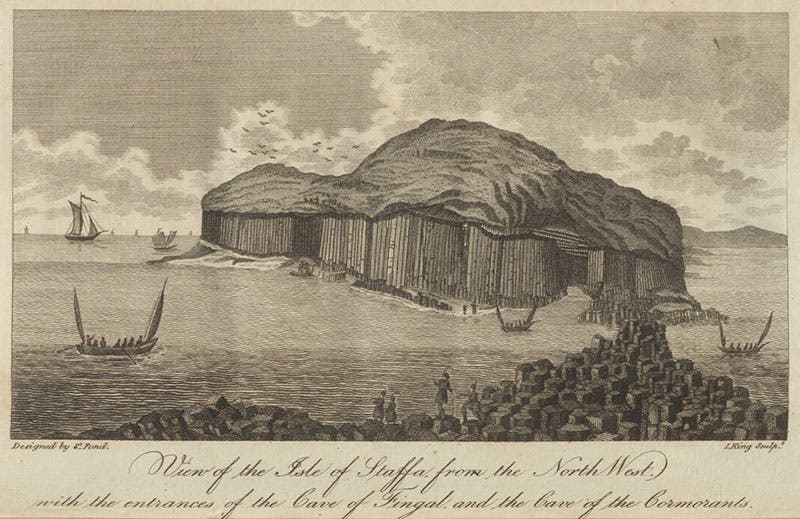

Barthélemy Faujas-de-Saint-Fond, a French geologist and scientific traveler, was born May 17, 1741. We have published three other posts on Faujas, which is highly unusual, but he was a multi-talented fellow; he participated in and chronicled the first balloon flights of the Montgolfier brothers (our first post), described a very large prehistoric reptile (a mosasaur) that was unearthed in Maastricht in the Netherlands (second post), and published a large folio on the formerly volcanic regions of central France (third post). (Our first two posts have gone missing; the links will become live when we have found or reinstalled them)

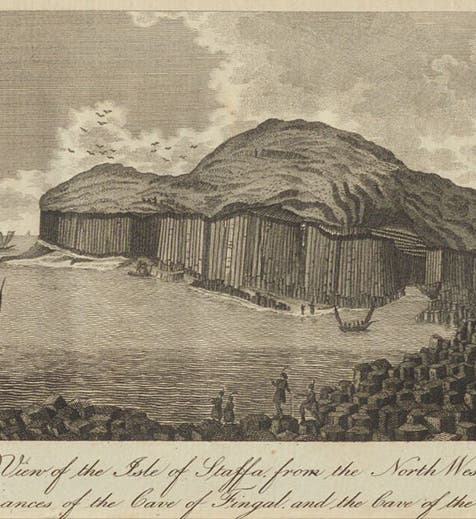

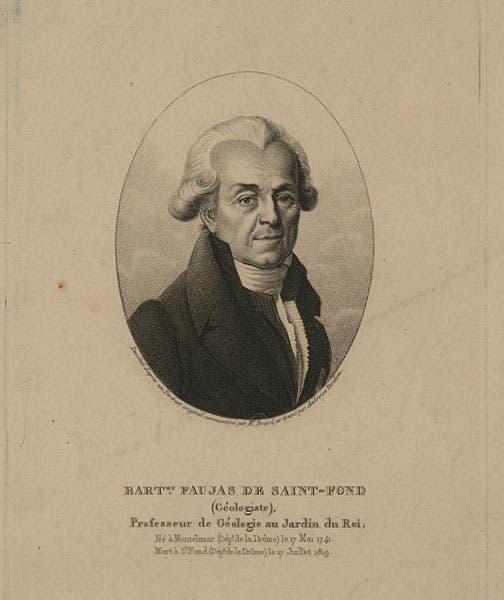

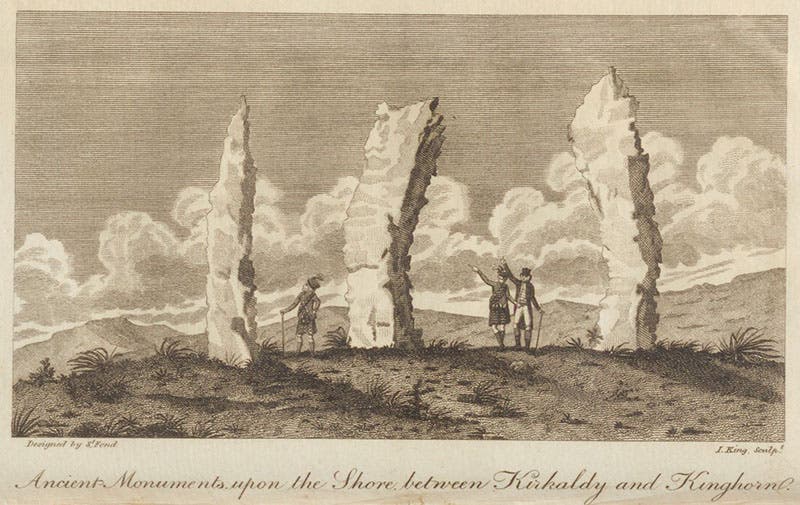

He merits a fourth post because in 1784-85, he undertook a geological tour of England, Scotland, and the Hebrides, and published a two-volume travel narrative in 1797, Voyage en Angleterre, en Écosse et aux îles Hébrides (the French Revolution came at an inconvenient time for the publication of the book). The account is well known for its illustrations of the Isle of Staffa and Fingal’s Cave (first and third images), which in fact were based on drawings commissioned by Sir Joseph Banks when he visited the area in the early 1770s. It also contains an engraving of some standing stones identified as “between Kirkcaldy and Kinghorn” in Fife, just above the Firth of Forth on Scotland’s east coast (fourth image); the area is not known for stone circles now, so I am not sure what the image represents, but it is a handsome one. Faujas thought they were probably erected by the Druids, rather than the Romans

Faujas also described meeting quite a few notable English scientists, such as Banks (who showed him around Kew Gardens), and Joseph Priestley and James Watt in Birmingham, and such descriptions are always of interest as providing contemporary color to figures that we usually encounter primarily in textbooks.

But Faujaus’s most interesting encounter was one that had not been noticed by historians of science until recently. Faujas stopped by the home of William Herschel and his sister Caroline in Dachet, near Windsor. Herschel built his own reflecting telescopes, and with one of them he had recently (1781) discovered a new seventh planet, which he called “Georgium sidus” (“George’s star”) after his king and patron, and which would soon be named Uranus. He then built a larger 20-foot telescope that he installed outside his house in Dachet. You can see several of his telescopes, including the 20-footer, at our post on William.

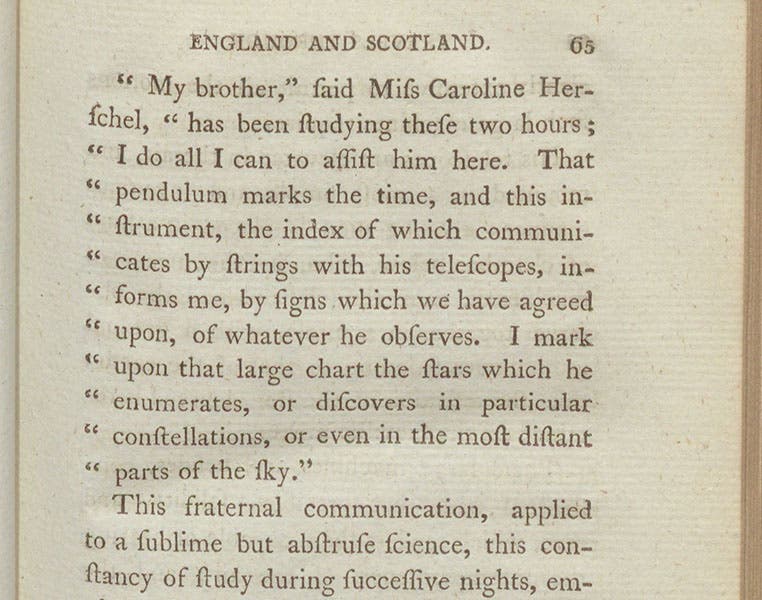

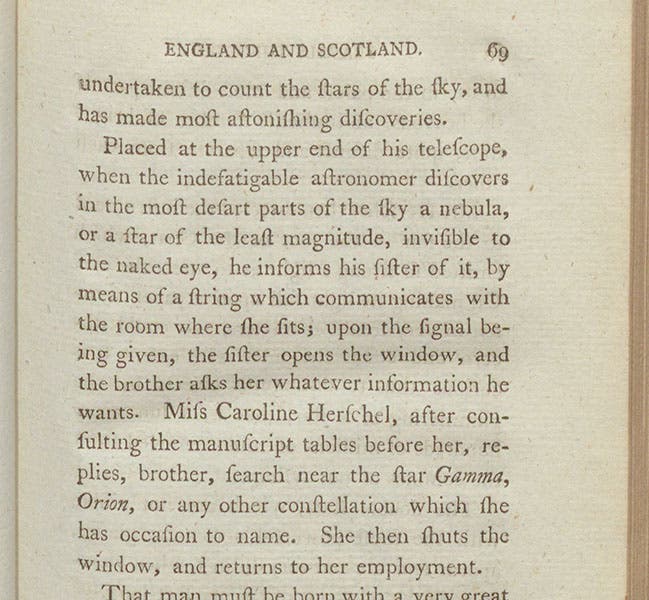

We have long known that William, in his observation program, worked closely with sister Caroline. To use his 20-foot reflector, he had to ride in a saddle high up on the front end of the telescope. So Caroline did all the record keeping – writing down the positions of observed objects (mostly stars or nebulae), looking up formerly observed objects in large celestial atlases and catalogues, and keeping continual track of the time with large clocks. But Caroline was inside, at a desk, and what we did not know was how they communicated with each other.

Faujas provided us with a unique eye-witness account of how William and Caroline collaborated. There was a cord that ran from the telescope to an index on Caroline's desk which provided the polar distance of the telescope, or the direction in which it was pointed. When William had made an observation, he plucked the string, using a code they had devised to indicate the kind of object he was observing. Caroline would then plot the polar distance, glance at the clock to determine the sidereal time, and pinpoint the object on a large celestial map (in fact, a copy of John Flamsteed's Atlas). If William needed information, he used a different code on the string, and Caroline would then open the window and answer William’s question. She then closed the window, and William moved on to his next celestial object. We show you several passages in Faujas’s Travels where he describes how they worked together, the first one quoting Caroline when he had just arrived (fifth image), the second recording his own observations of their collaboration (sixth image).

Faujas was at Dachet for only one night, but William and Caroline worked together for over 40 years. It was one of the most productive and extensive collaborations in the history of astronomical observing. We are fortunate that Faujas provided us with a first-hand glimpse of the team at work.

We have the first French edition of Faujas's Voyage en Angleterre (1797), as well as its near-immediate English translation, Travels in England, Scotland, and the Hebrides (1799) in the History of Science Collection. We chose to reproduce the text from the English translation, to provide access to all our readers, so it made sense to use the engravings from the same edition. However, they differ slightly from those in the 1797 edition, which are larger.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![Andromeda and Perseus, constellations figured by James Thornhill, with star positions determined by John Flamsteed, in Atlas coelestis, plate [15], 1729 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/1b30cfec-5be6-4297-a7fb-97255ba992e5/thornhill1.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)