Scientist of the Day - Barton Stone Alexander

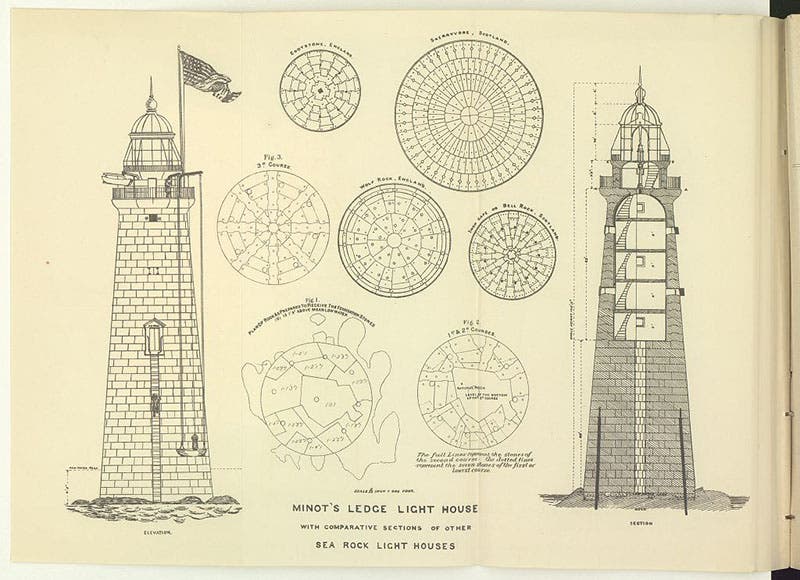

Barton Stone Alexander, an American engineer, was born Sep. 4, 1819. In 1853, Alexander took over construction of the Smithsonian Institution building,, after some dissatisfaction arose with the original architect, and saw it through to completion in 1855. But today we are going to discuss his role in the rebuilding of Minot's Ledge Lighthouse, near the south entrance to Boston harbor. The ledge, which lies just under water, was a real threat to ships, but it was difficult to erect a beacon there, because of the fact that there is no dry land to build it on. An iron structure was put there in 1850, but it was no match for storms and tides, and it washed away within a year, along with two keepers. The task of designing a replacement was given to Joseph Gilbert Totten, chief engineer for the U.S. Army. For a model, Totten turned to the Eddystone Lighthouse, another structure built on a difficult, near-underwater site. John Smeaton, who designed and built the Eddystone light, had used granite stones dovetailed into the bedrock and then to each other, with iron rods and stone keys for further strengthening, and the lighthouse was still in place a hundred years later. The Minot's Ledge Light was designed with a similar plan, using interlocked stone blocks (second image). We wrote a post on Totten once, as well as one on Smeaton. But Alexander was the one who actually built Minot's Ledge Light, and we thought we would give him his due today.

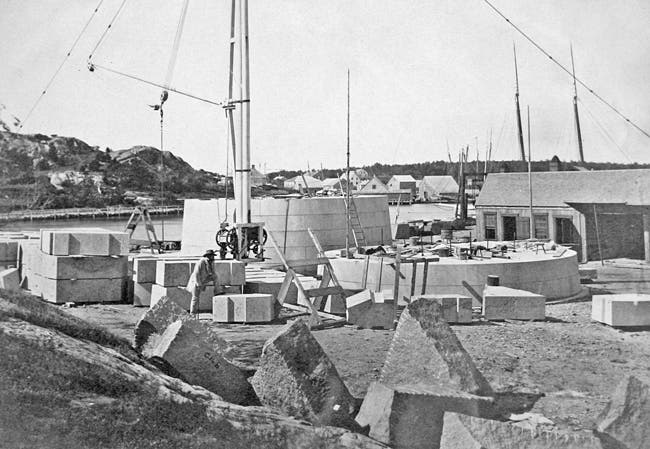

Construction on the lighthouse began in 1855, and the initial work was very difficult, because it had to be done from a moving ship at low tide. The stone chosen was granite from Quincy, Mass., on the south shore of Boston Harbor, which was ferried to Government Island, part of Cohasset, the closest town to Minot's Ledge, and then cut to shape and test-assembled (third image). The blocks, about 3 tons each, were then shipped, one by one, to the offshore ledge.

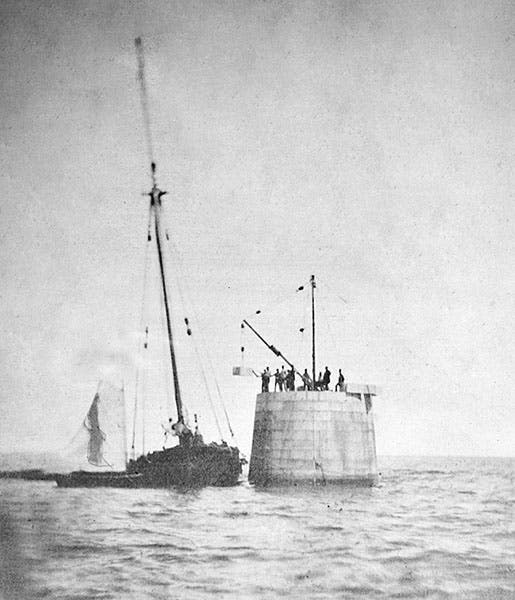

Very slowly, the interlocked blocks of Quincy granite rose from the sea. There was so much concern for the stability of the lighthouse that the lower forty feet was built completely solid, with no openings at all. So to enter the lighthouse, you have to climb a forty-foot exterior ladder to get to the door, a ladder that you have to grab onto from a heaving boat. Once out of water (fourth image), the lighthouse rose more quickly, to its eventual height of 114 feet. The final stone was laid June 29, 1860. The lighthouse was equipped with a second-order Fresnel lens, and the lamp was first lit on Nov. 15, 1860. The lenses have been replaced, twice, but the lighthouse still stands, a testament to Totten's design and Alexander's engineering skills.

The stories of the building of the Eddystone light, and the Bell Rock lighthouse by Robert Stevenson, are both well known, because each builder published an elaborate account of the process, with ample illustrations of the complicated designs and difficult conditions. Alexander intended to write such a book, and assembled material for it, but it was never put together and published – no doubt the intervention of the Civil War did not help. In the absence of such a work, Alexander's achievement, which is certainly the equal of Smeaton's and Stevenson's, has remained under-appreciated.

Although it is still there, the Minot's Ledge Lighthouse is no longer owned by the U.S. Coast Guard. In 2014, declaring it no longer necessary, the Coast Guard sold it to the highest bidder, who happened to be Bobby Sager, a "lighthouse philanthropist" who had earlier purchased a lighthouse in Maine and has since bought one in Michigan. We realize it is expensive to maintain a lighthouse that is not being used, but we are not so sure the government should have been selling off what certainly ought to be a National Historic Landmark. After all, the purchaser could have been someone who had his eyes on six million pounds of polished Quincy granite.

Until recently, we had no good portrait of Barton Alexander, but earlier this year there was an auction of some Civil War material, from which we borrowed this photograph of our intrepid engineer (fifth image).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![Andromeda and Perseus, constellations figured by James Thornhill, with star positions determined by John Flamsteed, in Atlas coelestis, plate [15], 1729 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/1b30cfec-5be6-4297-a7fb-97255ba992e5/thornhill1.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)