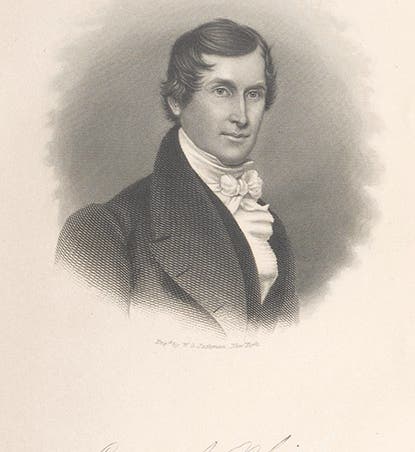

Scientist of the Day - Canvass White

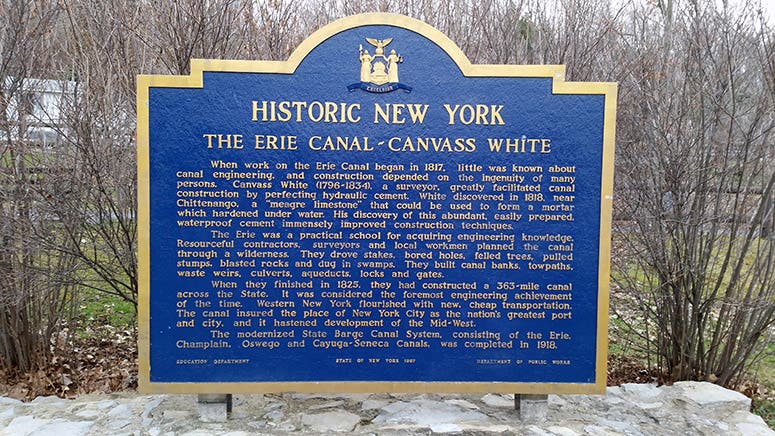

Canvass White, an America civil engineer, was born Sep. 8, 1790, in upstate New York. White was a member of the first generation of civil engineers who were so vital in building first the canals, then the railroads, that made possible both eastern prosperity and western expansion. The father of American engineers was Benjamin Wright, who was trained by an English engineer. Wright was put in charge of building the Erie Canal in 1816, and he brought in White as one of his first engineers, although White had zero experience, his only qualifications being that he was bright, good at math and physics, and knew some chemistry. None of the five engineers on that initial panel had any training, except for Wright, and that was minimal. Wright and New York Governor DeWitt Clinton decided they needed to tap into English engineering practices, and so in the fall of 1817, they sent White overseas, to see what he could learn, and in six months, he learned a lot. He walked the entire canal system in Wales, and also in the midlands, some 2000 miles on foot, talking to engineers whenever he could. One feature that particularly impressed him was the Pontcysyllte Aqueduct, built to carry the Ellsemere canal over the River Dee in Wales. It was 1000 feet long and 120 feet tall, supported on cast iron piers, and was designed and built by the father of all civil engineers, Thomas Telford. We showed the Pontcysyllte Aqueduct as the second image in our April Fool’s post on Eleazar Root last year (you can also see it in the background of the portrait in Telford’s post). White also learned about hydraulic cement – cement that will set under water – which English engineers such as John Smeaton and Telford had learned how to make, recovering the practices of the ancient Romans. White absorbed all this like a sponge and returned in the spring of 1818 to put this knowledge into practice on the canal. He also brought back, as part of his assignment, many levelling and surveying instruments from England, since the ones the Americans were using were crude and would have been ill-suited to the requirements of laying out the Erie Canal, as they were already discovering.

White quickly became Wright’s most trusted associate on the Erie Canal project. He helped re-survey much of the route and suggested changes that were usually adopted; when they were not, difficulties often ensued. White also immediately went looking for local sources of hydraulic cement, and found them, first in Madison County, and then at other locations along the canal route. Hydraulic cement has to be manufactured; once a source is found, the limestone is heated in a kiln and then crushed to just the right-sized powder and mixed with sand. White patented his cement in 1820, but he was never able to sustain his patent rights, as the canal commissioners ignored them when they took bids. But it is certain that White with his cement saved the entire canal project. They had planned to use ordinary cement to line the canal, facing it with a thin layer of expensive imported hydraulic cement, but we now know that would have broken down in just a few years. Having local hydraulic cement meant they could build the entire canal with the waterproof cement, and it would not deteriorate. And it did not.

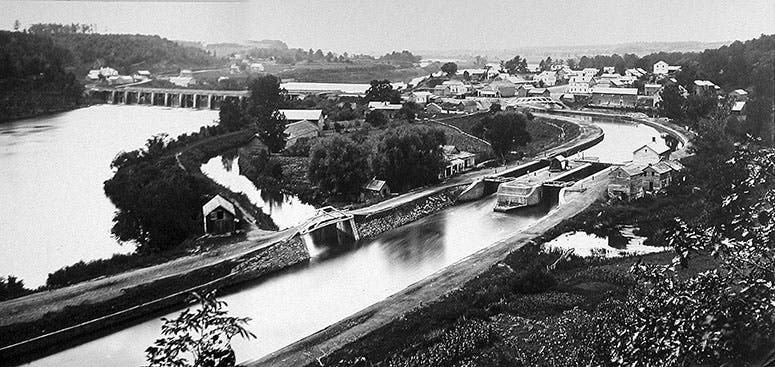

White also had a go at building a river-crossing aqueduct, constructing a pair to carry the Erie Canal over the Mohawk River and back at what is now Rexford, New York, not far from the Canal’s eastern terminus, at the Hudson River. White’s aqueducts were 750 and 1200 feet long and carried the canal 25 feet above the river. It wasn’t quite the Pontcysyllte Aqueduct, but his timber and stone aqueducts were, along with the 5-step locks at Lockport, the engineering wonder of the Erie Canal. They were replaced when the canal was widened, so we don't know that the original aqueducts looked like, but we have a turn-of-the 20th-century photo of the replacements, which were in the same locations as White's constructions (third image, above).

By 1823, White was the most respected young engineer in the country, and he received offers from the states of Ohio and Pennsylvania to engineer their canal systems, and from New York City to increase their water supply. He passed on the offer from Ohio, and he did help initiate the Croton Aqueduct project for New York City, but we have room here to mention only White's involvement in the building of the Union Canal in Pennsylvania. This was part of a navigation project intended to connect the Susquehanna River system to the Schuylkill River, so that commerce (especially coal) could be brought directly to Philadelphia, instead of having to go first to Baltimore. White came to the Union Canal project in 1824, bringing with him three other young engineers from the Erie Canal enterprise. In four years, they completed the 80-mile canal, from Middletown to Reading, and four years later had added a feeder canal that provided access to anthracite coal. The engineering highlight of the canal was the Union Canal Tunnel, 730 feet long, drilled through hard rock from both ends (fourth image, above). There had been no tunnel like it anywhere in North America. It is still there, now a National Historic Landmark, just east of Lebanon, Pennsylvania.

White was soon involved in many more canal projects than he could comfortably handle: the Farmington Canal in Connecticut, the Delaware and Raritan Canal in New Jersey, and quite a few others. His canal projects also began to run into competition from railroads, which started to extend tentacles in 1830. But before that confrontation built to a head, White simply ran out of life, as his health deteriorated rapidly. He moved to St. Augustine in Florida to recover, but he did not, dying shortly after he arrived, on Dec. 19, 1834. He was 44 years old. His body was returned to New Jersey and was interred in the Princeton Cemetery. We show here photos of his above-ground sarcophagus, and a bronze portrait relief at the grave (fifth and sixth images, above).

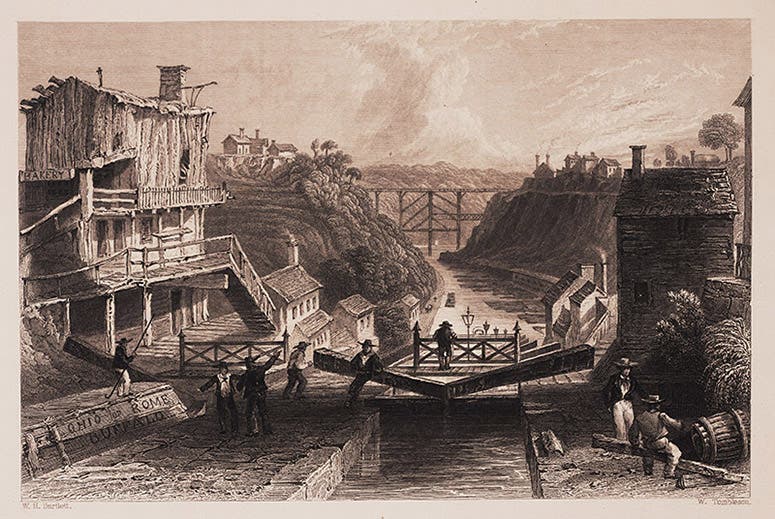

The Erie Canal provided the opportunity for American civil engineering to establish itself, really from nothing, like a technological Big Bang. No one took better advantage of it than White. One of my favorite images of the young Erie Canal is one I used in the post on Benjamin Wright, and which I reproduce again here (seventh image, above). It shows a threshold being crossed, that leading from building to engineering, and engineering on a large scale. It is sobering to realize that when it was published, on the 15th anniversary of the completion of the canal, White, a principal architect of the Erie Canal, had been dead for 6 years.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.