Scientist of the Day - Charles Darwin

On June 18, 1858, Charles Darwin got the shock of his life. We have written a number of posts about Darwin, discussing his portrait history, his prolonged study of barnacles, the publication of the Origin of Species, and his funeral in Westminster Abbey, but we have never written a Darwin post about this traumatic day in his life. He was 49 years old, had been chewing the cud of his theory of evolution by natural selection for nearly 20 years, had completed a monumental four-volume work on barnacles, and was slowly churning out what would surely be a massive and meticulous tome on "transmutation," as Darwin called the idea that species are not fixed, but change slowly, due to natural variation, the fecundity of life, and the pressure of the struggle for existence. He had been working for over two years on what is sometimes called the "Big Book" and was still on the topic of variation under domestication, a subject he would later cover in the very first chapter of The Origin of Species.

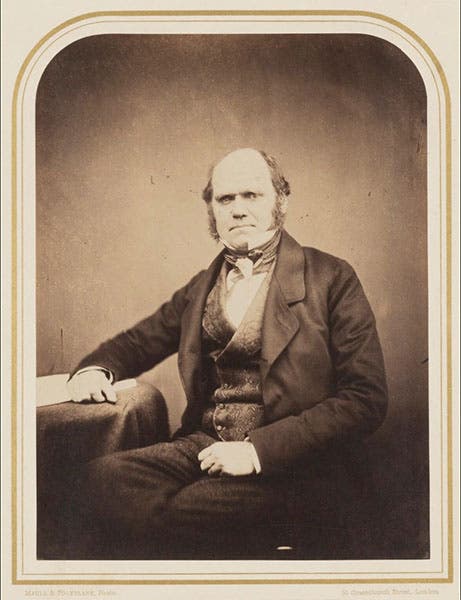

Darwin was moderately healthy, although he continued to suffer from an unknown and lifelong ailment that continually upset his stomach and sapped his energy, but he was not much worse than usual. At the moment, none of his children were ill (although that situation would change shortly), and his wife Emma was doing well, tending the new baby; life at Down House, away from “dirty smoky London,” was good. And then the post arrived, bearing a thin package from the far-away island of Ternate in the Malay Archipelago. Darwin recognized the hand-writing – it was that of Alfred Russel Wallace, a younger Welsh naturalist whom he knew by correspondence but had never met, to his recall, and who was now exploring the Spice Islands.

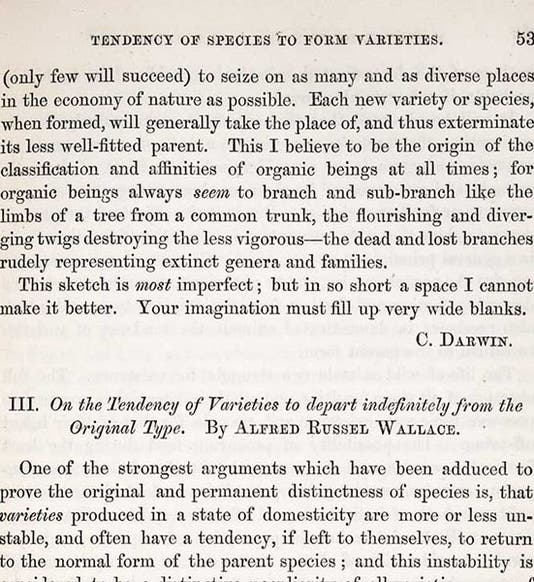

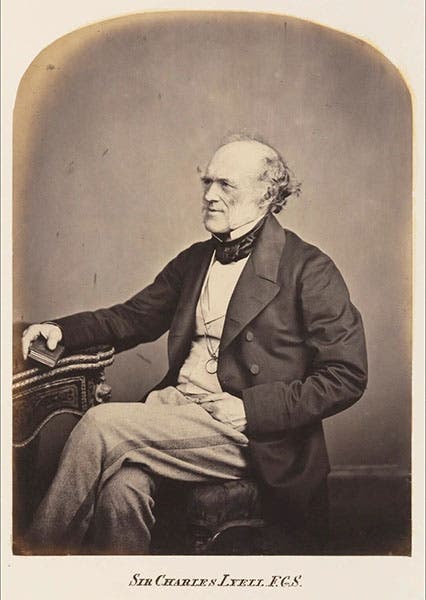

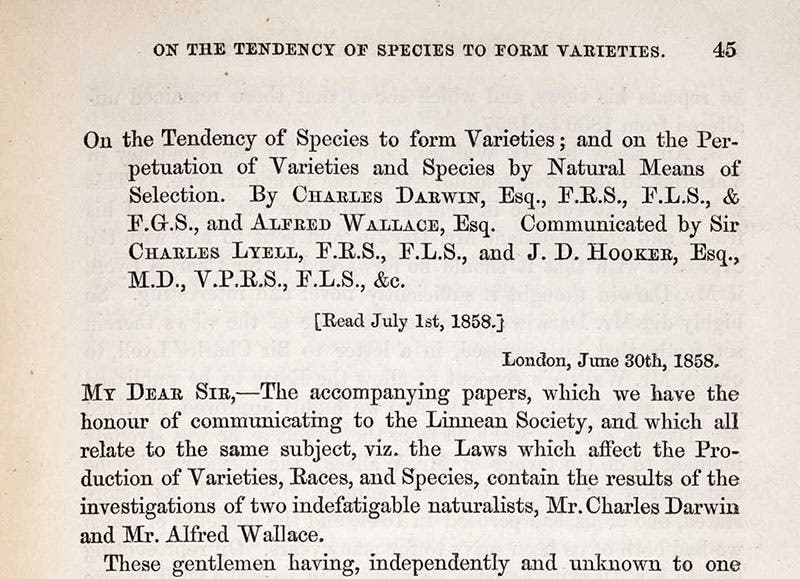

Inside the packet was a letter, and a short, hand-written manuscript. The letter invited Darwin to read the manuscript, titled “On the Tendency of Varieties to depart indefinitely from the Original Type,” and then send it on to Charles Lyell (fourth image) for possible publication. Darwin, intrigued, read the manuscript, and his heart must have sunk to the floor. For Wallace had set down in outline the idea of evolution by natural selection, the very theory that Darwin had been working out for 20 years. As Darwin commented, Wallace could not have done a better job if he had been looking at Darwin’s own outline that he had written back in 1842. It was all there, and Darwin was greatly distressed. Charles Lyell had told Darwin that if he put off publication too long, someone else would beat him to the finish, and that is exactly what had happened.

Darwin was an honorable man – he could have destroyed the manuscript and no one would have been wiser – but he did as he was asked, sending the manuscript on to Lyell that very day, with a cover letter, which you can read at this link on the Darwin Correspondence website (the original letter from Wallace to Darwin does not survive).

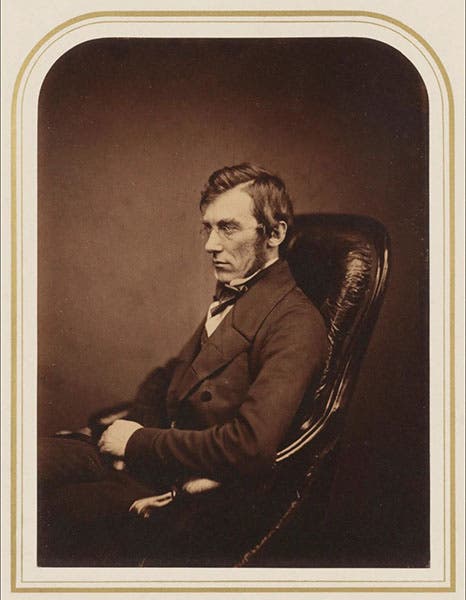

Then, to his credit, Dawin pulled out of his funk and set to the task of figuring out what to do next. With the advice of Lyell and Darwin’s best friend, Joseph Hooker (fifth image), it was decided that it would be no breach of scientific etiquette if Darwin should cobble together a short paper from material he had already written and circulated, and have it published along with Wallace’s paper. And that is what transpired. The two papers were read to the Linnean Society of London on July 1, 1858, and published in the Society’s Journal (sixth image; first image). Darwin took little part in most of this – his daughter Henrietta came down with a fever, possibly diphtheria, the very day Darwin got his fateful letter, and several days later, baby Charles Waring Darwin fell ill, an illness from which he would not recover. The baby died on June 28, and a grieving Darwin paid scant attention to the events in London of July 1.

But it all turned out for the best. Darwin abandoned his “Big Book” in favor of a shorter work that would eschew footnotes and concentrate on explaining the idea of evolution by natural selection and showing that it had more explanatory power than special creation. He wrote that book in just over a year, and when it was published as On the Origin of Species in November of 1859, Darwin’s priority was reestablished. Wallace, as it turned out, had done Darwin a great favor by awakening him from his slumber with a punch in the gut on that momentous day of June 18, 1858.

I have always liked Jacob Bronowski’s description, in The Ascent of Man (1973), of Alfred Russel Wallace as “the man from Porlock in reverse,” when referring to the encounter of June 18. I wrote a post about this once, called /Kublai Khan, where you may glean the details.

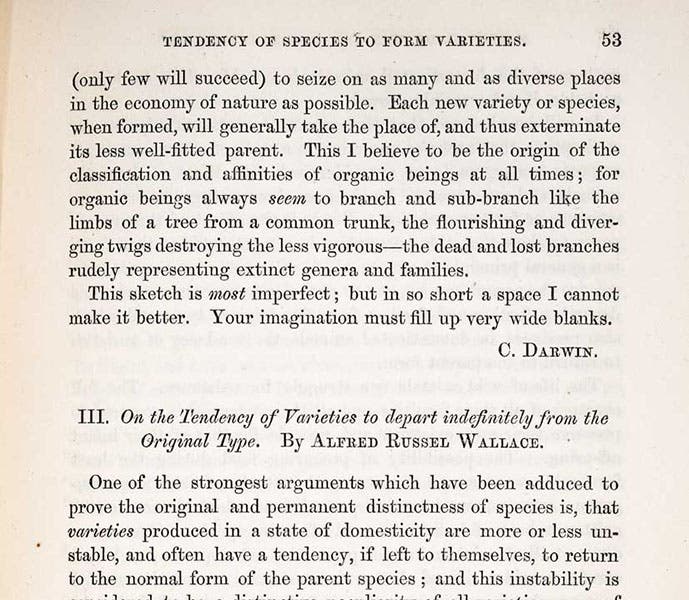

In our post on Darwin’s portraits, we did not show any from the 1850s, because none of the four I know about is a great likeness. The one we show here, a photo taken by the London photographers Maull & Polyblank around 1855, was Darwin’s least favorite portrait, and he urged Hooker, who had a print hanging on his wall, to burn it. He thought it made him look “atrociously wicked.” He does have a gleam in his eyes.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![Agama colonorum (Spiny agama), hand-colored lithograph, cropped, Neue Wirbelthiere zu der Fauna von Abyssinien, by Eduard Rüppell, [v. 3] Amphibien, plate 4, 1835 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/42f3e8a2-b691-4d33-abd7-55d0d07fc1be/Ruppel%201.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)