Scientist of the Day - Charles-Marie de La Condamine

Charles-Marie de La Condamine, a French mathematician and astronomer, was born Jan. 27, 1701. In 1734, the Royal Academy of Sciences in Paris decided to send out two geodetic expeditions to Lapland and to Ecuador to measure the length of a degree of latitude at these two locations, one right on the equator, the other near the Arctic Circle. The purpose was to settle a long-simmering controversy over the "figure of the Earth. Isaac Newton had argued that a spinning Earth must flatten out at the poles, acquiring an oblate shape, resembling a grapefruit (the analogy is ours – Newton had never seen a grapefruit). Many French scientists believed that the Earth is prolate, looking rather like a lemon. One way to determine the Earth's shape was to measure the length of a degree at the equator; at some middling latitude (like Paris); and then at a high latitude. If the Earth is shaped like a grapefruit, then a degree will be longer at high latitudes than at the equator. If it is lemon shaped, then the reverse is true. The French had already measured the length of a degree at the latitude of Paris, determining it to be a little over 69 miles in length. It only remained to compare that figure with the ones to be obtained in Lapland and Ecuador.

La Condamine was one of three Academy members chosen to travel to Ecuador; the other two were Pierre Bouguer and Louis Godin. This would be a much more arduous task than the Lapland expedition, because it would take nearly two years just to get there and back, and then you would have work at an average altitude of nearly two miles, smack in the middle of the two ranges that make up the Andes. The task would be further complicated by the fact that the academicians would have to get permission every step of the way from the authorities of the Spanish Viceroyalty of Peru, and the French and Spanish were not getting along all that well. They hoped to finish their measurements in a single year, which with travel time would add up to about 3 years. As it happened, it took over nine years to do the job.

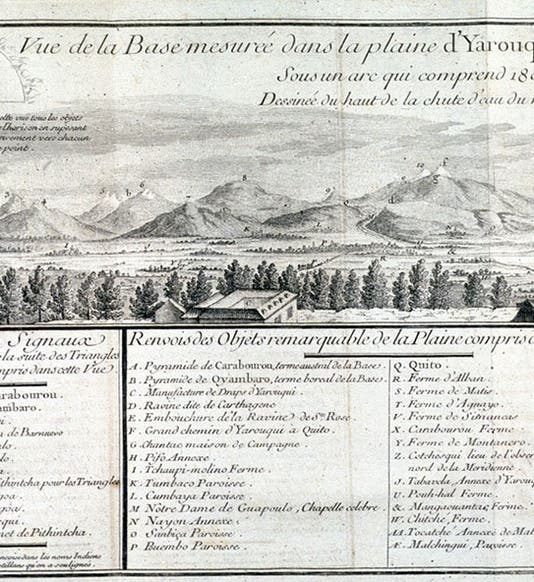

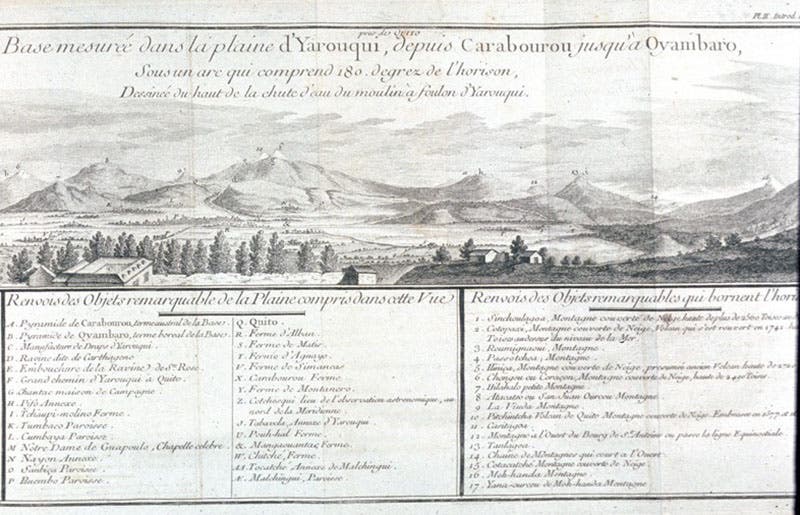

It started relatively smoothly. All attempts to measure a degree of latitude proceeded the same way. First, you had to lay out a baseline, the longer the better, which had to be on fairly level ground where you could see from one end to the other. La Condamine found such a place on the Yaruquí plain, just east of Quito. They had 7 miles of flat terrain on which they could lay out their line. Then, this baseline had to be measured. This was accomplished with 20-foot-long measuring rods that were precision-made with copper ends, so that they could be laid end to end with great accuracy. Each team (there were two teams, going in opposite directions, making duplicate measurements that could then be cross-checked) had three measuring rods, and a six-foot iron toise brought from Paris that provided a standard length to calibrate the rods. For much of 1736, La Condamine and his team put down a rod, abutting a rod laid down earlier, shimmed it until it was level, made notes, and then put the third rod in place, slowly leap-frogging across the Yaruquí plain. The 7-mile baseline as measured was accurate to a fraction of an inch.

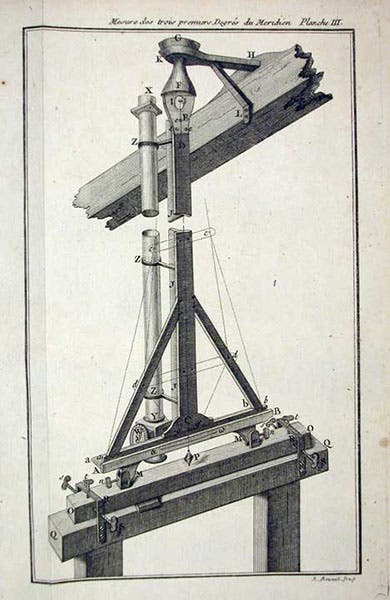

Then the surveyors took over. From each endpoint of the baseline, they used theodolites to sight on a distant point, in this case a marker erected on one of the mountains tops, of which there were many to choose from. With the two angles measured and the length of the baseline known, they were able to lay out on a map a triangle, with the lengths of the two new sides known with great accuracy. From one of these new sides, another triangle was laid out and measured, and they proceeded to triangulate their way south, for over two hundred miles, far enough to measure a full three degrees of latitudes. Finally, by sighting on a star (epsilon Orionis) from the two endpoints and determining the latitude of each, they could calculate the length of one degree.

All this should have been straightforward. The enterprise was complicated by wars that broke out; by instruments that proved to be inaccurate, requiring all measurements to be retaken; and by a growing enmity between La Condamine and the two Spanish officers that accompanied and, at least initially, assisted the French.

But after nine years of work, they were able to calculate the length of a degree at the equator. It was some 68.7 miles, less than that of Paris, which in turn was less than that of Lapland. The Earth is flattened at the poles, just as Newton predicted.

La Condamine took the hard way home, floating down the Amazon from the Andes to the Atlantic Coast. He eventually wrote two books about the geodetic expedition to Ecuador, both of which we have in our collections, Journal du voyage fait par ordre du roi, a l’équateur, and Mesure des trois premiers degrés du méridien dans l'hémisphere austral, both published in 1751 (fifth and sixth images). We show here some of the engravings from those two works. The most striking is a fold-out plate in the Journal, which shows the baseline on the Yaruquí plain, with a 180° panorama of Andean mountains and volcanos in the background. Since I was unable to shoot the entire plate with my camera, I shot first the left and then the right (first and third images). The volcano Pichincha that lies just outside Quito is the letter “f” in both images; Quito is Q, and the active volcano Cotopaxi is number 2 at the far left of the first image. The other plate (fourth image) shows one of the expedition’s zenith sectors, which were used to determine astronomically the latitude of the two endpoints of the triangulated line.

For more on the expedition to Ecuador, see our posts on Pierre Bouguer and Jorge Juan y Santacilia, one of the Spanish members of the enterprise, For the Lapland expedition, which lasted barely two years, see the posts on Alexis Clairaut and abbé Réginald Outhier.

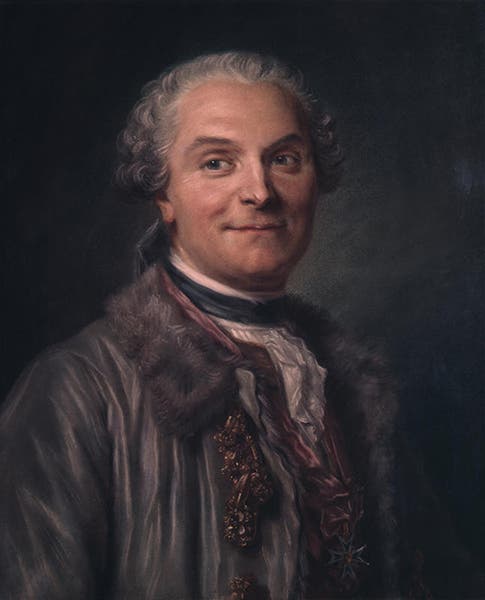

The portrait of La Condamine that we include here is a pastel, painted by Maurice La Tour in 1753, and now in The Frick Pittsburgh.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![Andromeda and Perseus, constellations figured by James Thornhill, with star positions determined by John Flamsteed, in Atlas coelestis, plate [15], 1729 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/1b30cfec-5be6-4297-a7fb-97255ba992e5/thornhill1.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)