Scientist of the Day - Charlie Taylor

Charles Edward Taylor, an American mechanic and machinist, was born May 24, 1868. We had hoped to write a notice on his birthday, but it didn’t work out. However, since Wilbur Wright was our Scientist of the Day yesterday, today seems the perfect occasion to celebrate Charlie, for he was the man who provided the Wright brothers with an engine for their famous flights in the Flyer in 1903, when no one else could do so.

Charlie went to work for the Wright brothers in 1901, building and repairing bicycles in their shop in Dayton, Ohio. He essentially ran the store while Wilbur and Orville were constructing gliders and running off to Kitty Hawk, North Carolina to learn how to fly them. Once they mastered the difficult art of flying their gliders, the Wright brothers decided in 1902 that it was time to attempt powered flight. They wrote to engine manufactures all over the country, asking if anyone could make a gasoline engine that supplied 8 horsepower and weighed less than 180 pounds. No one could provide such an engine at an affordable price. Charlie had often told his employers that he could make anything out of metal, and his performances in the shop, fabricating bicycles, did not belie his claim. So Wilbur and Orville in December of 1902 asked Charlie to build them an engine.

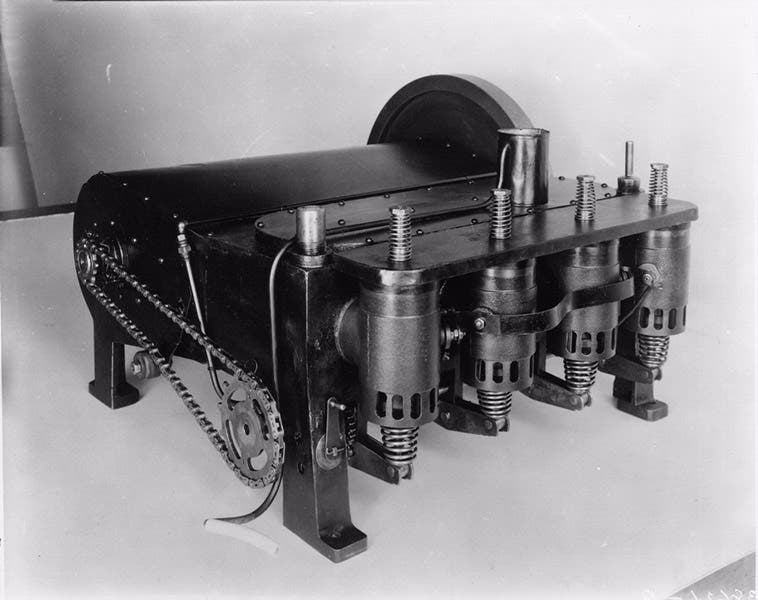

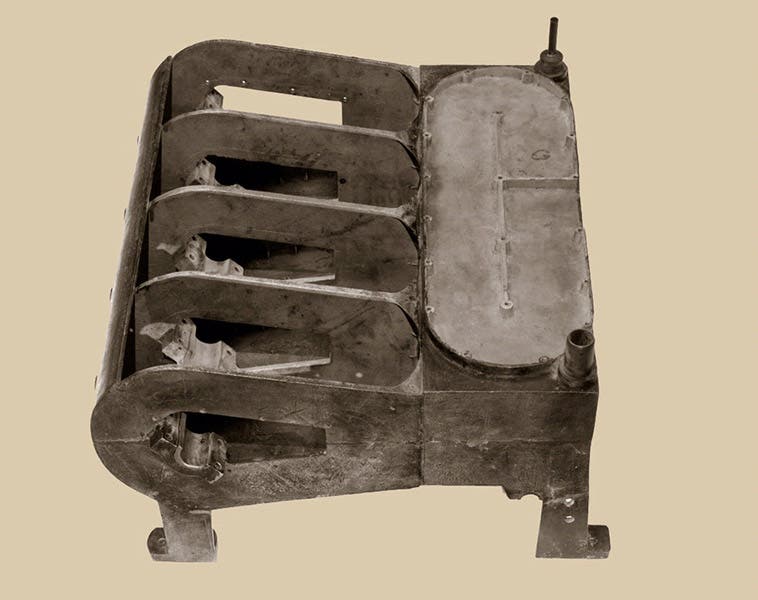

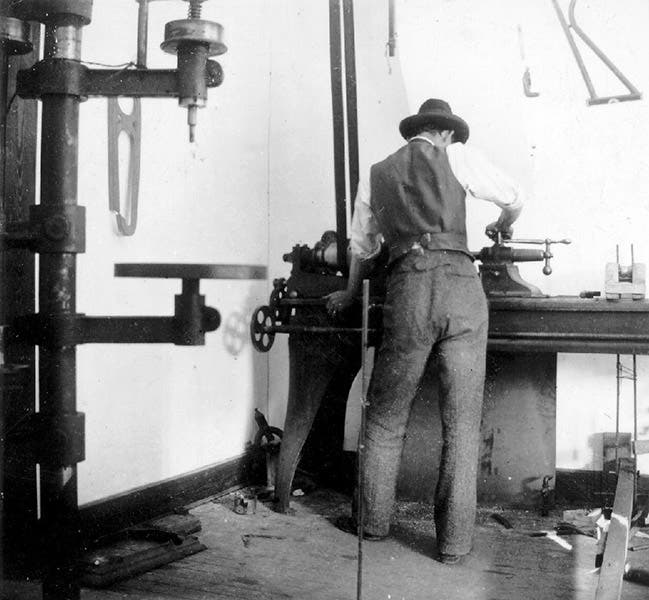

Charlie ordered some aluminum from Pittsburgh and had a local foundry cast the engine block, and he amassed the needed machine steel and set to work. In six weeks, he fashioned a complete working gas engine from bar stock, using only a drill press and a lathe in the back of the Wright brothers' shop. We can see his actual working tools in a photo of Wilbur in the shop, where both lathe and drill press are visible (fourth image).

Taylor cut the crank shaft out of a solid steel bar – a 30-inch-long 2x6, using the drill press as a saw and removing the rough edges with a hammer and chisel, finishing up on the lathe. He drilled the block to accommodate the four cast-iron pistons, turned the pistons, cut grooves for the piston rings, and fashioned bearings, all in a shop set up to produce bicycle frames. And he had no written plans except for a few sketches on scrap paper, provided by Wilbur and Orville.

His first engine worked well, and supplied 12 horsepower, a welcome surplus, while coming in at less than 180 pounds. The first engine failed when the block cracked, a result of a gasoline leak that froze the bearings, so Charlie ordered another block and did it all over again. The second engine was shipped to Kitty Hawk and was the power source for the famous first day of powered flight, Dec. 17, 1903. The National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C., has this engine, and we include several views of it here – intact, opened up, and sitting on the wing of the Flyer. You could also view yesterday’s post on Wilbur, where the last image is a fine view of the Flyer on display, with the engine just visible on the wing next to the Wright mannikin.

Wilbur Wright famously said once that the key to powered human flight was not the engine, but rather the acquired knowledge of how to control an inherently unstable vehicle. Nevertheless, without a light engine generating sufficient horsepower to turn the propellers at the necessary speed, the Flyer would have gone nowhere. And the Wright brothers knew they had a jewel in Taylor. He built all the engines for the various Wright aircraft for the next 8 years, and continued to serve them as chief mechanic until 1920.

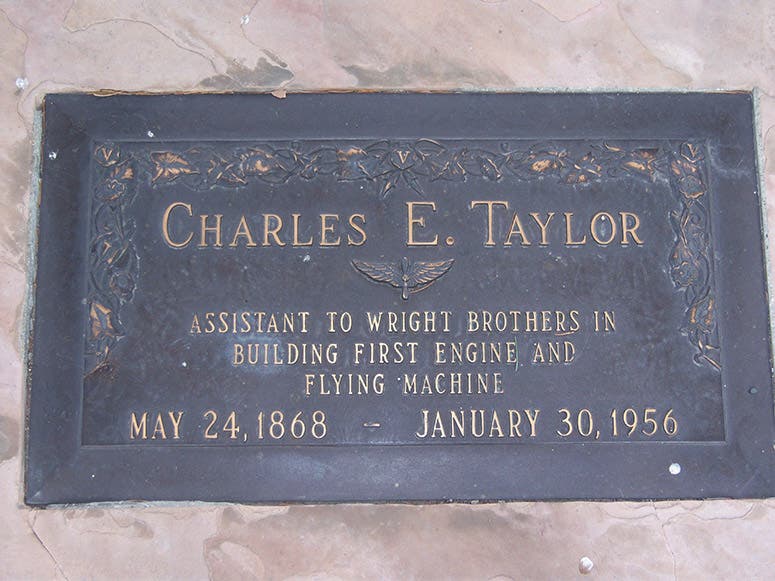

Charlie lived a long life, reaching the age of 87, and the last half of his life did not contribute nearly as much to his self-esteem as the first half, since his seat-of-the-pants skills became less essential to a maturing aircraft industry. But things brightened in his last few years, as historians of technology came to realize how essential Charlie had been to the Wright brothers’ success, and during the Golden Anniversary celebrations of 1953, Charlie finally received the attention he had deserved all along. When he died in 1956, he was buried in the Portal of the Folded Wings Shrine to Aviation in Burbank. This rotunda had once been the entrance to an adjacent cemetery, but it was bought by a wealthy aviation fan and in 1953 was transformed into a memorial for deserving but unsung aviators. As an architectural specimen, it leaves me shaking my head (here is a view of the exterior), but if the rotunda provides a resting place for aviation heroes who would otherwise lie in unmarked graves across the country, I am all for it. The ashes of fourteen early aviators are entombed here beneath memorial plaques (sixth image); they are joined by the remains of one aircraft mechanic, Charlie Taylor. His plaque comes to us courtesy of a visitor who uploaded it to Flickr (seventh image).

In 2014, the U.S. Air Force added a bronze bust of Charles Taylor to their National Museum in Dayton (second image). Charlie was the first aircraft technician ever so honored. He is now a hero to all living aircraft mechanics, and the namesake of an annual award that honors the best aircraft technician in the country.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.