Scientist of the Day - Christian Doppler

Christian Andreas Doppler, an Austrian physicist, was born Nov. 29, 1805, in Salzburg. Doppler was educated at various schools in Vienna and Salzburg, and began publishing papers in his twenties, but he had difficulty breaking into the Austrian academic system, and was on the verge of moving to America when he finally landed a position at a technical school in Prague in1840, and with that an associate membership in the Königliche Böhmische Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften (Royal Bohemian Academy of Science) in Prague.

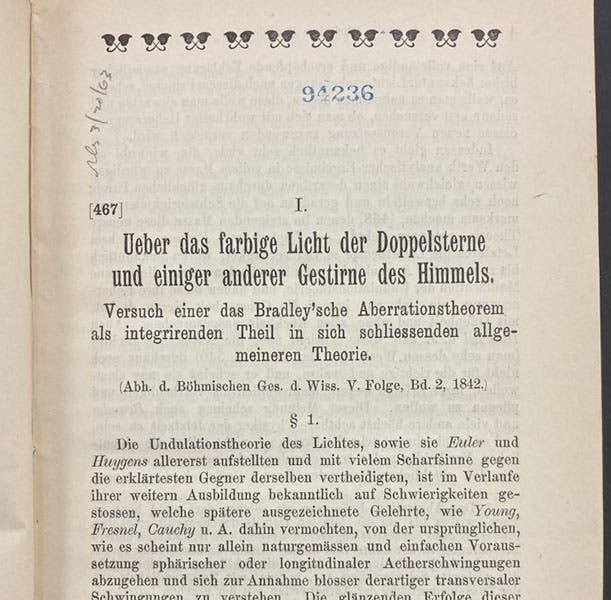

In 1842, Doppler presented a paper to the Academy which would become his best-known contribution to mathematical physics. It was called "Ueber das farbige Licht der Doppelsterne und einiger anderer Gestirne des Himmels” (“On the colored light of double stars and some other heavenly bodies”). In this paper, Doppler announced a new kind of optical and acoustical effect. He predicted that if light were emitted from a source moving toward the observer, the wavelength of the light would shorten and become bluer, and if the source were moving away from the observer, then the waves would get longer and redder. He provided equations that would allow one to calculate the shift in wavelength exactly. He thought (incorrectly) that this “Doppler effect” (our term, not his) would explain why two stars orbiting each other often differed in color.

Doppler reasoned that the same shift in wavelengths would occur with sound waves, so that if a sound source were coming towards us, the pitch of the sound would be higher than expected, while the pitch would drop if the source moved away. We now call such a change in frequency a "Doppler Shift", and it is a very real effect.

One might wonder why no one had noticed this before Doppler predicted it mathematically. With respect to light, we can understand why, because you cannot tell if a light wave has shifted frequency without a marker, and those markers, called spectral lines, were not understood until 1859 (see our post on Gustav Kirchhoff). But a change in the pitch of a sound – how hard is that to detect? The fact is, things didn't move very fast in those days, so shifts in pitch were very small, and you would have to be looking for such a shift to detect it. Such was the case with the Dutch physicist Buys Ballot, who, in 1845, loaded a bevy of horn players onto a railroad flat car and pulled them through a station, trumpeting all the while. The pitch did indeed drop as the flat car passed by, the first experimental confirmation of the Doppler effect (third image). Nowadays, the Doppler shift of light is used to detect invisible planets, measure the distance to far-away galaxies (a galaxy’s redshift is proportional to its distance from us), unravel the nature of quasars, and, most recently, to detect that the expansion of the universe is speeding up.

Doppler's classic paper of 1842 is one of the very few milestone journal articles that is not to be found in the Linda Hall Library; we have most of the volumes of the Abhandlungen of the Bohemian Academy, but there is a short run that was missing from the American Academy of Arts and Sciences Library long before we acquired that collection, and Doppler's paper just happens to fall in the middle of that missing run.

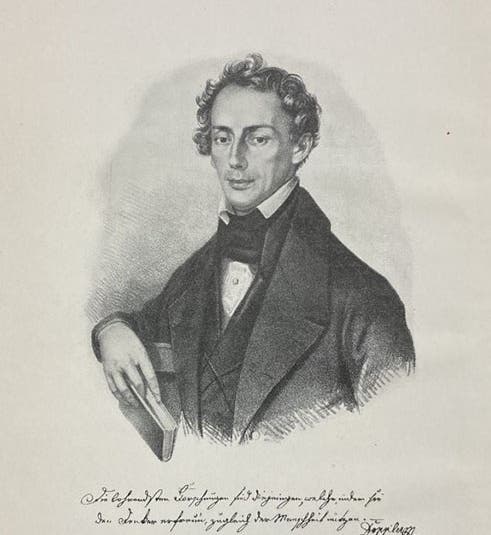

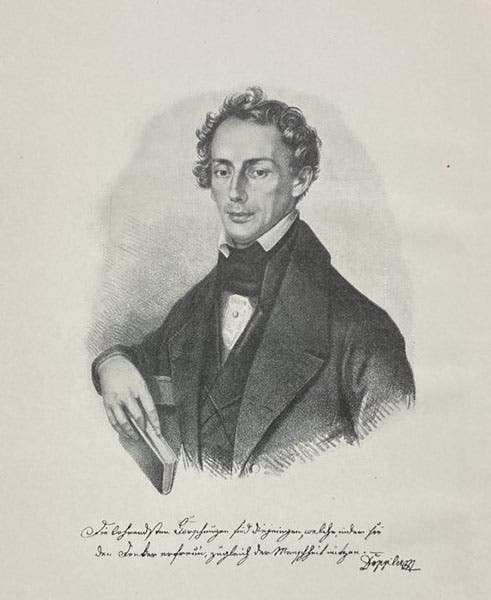

Fortunately, Doppler’s paper of 1842 and ten other Doppler papers were reprinted in 1907 as one volume in a series knows as Ostwald’s Klassiker der exacten Wissenschaften, with notes by none other than Hendrik A. Lorentz, who provided the equations for Einstein’s theory of special relativity, and who won the 1902 Nobel Prize for Physics. We do have this work in our collections, and we show the first page of the reprint of Doppler’s famous article (second image), as well as the frontispiece portrait of Doppler (first image).

Doppler’s reputation rose rapidly, and in 1850, he was appointed director of the Physical Institute in Vienna and professor of physics at the University of Vienna. But his remaining years were few. He had long suffered from a debilitating lung disease, and he moved to Venice in 1852, hoping the change in climate would help. But it did not, and he died there on Mar. 17, 1853, just 47 years old. He was buried in San Michele cemetery in Venice, where there is a plaque in his honor in a cloister (fourth image).

There is a lovely color portrait of Doppler that appears in several online sources, and it does look like him, but it is undocumented in all its appearances, so we only link to it here. If it is a valid portrait, I hope someone will let me know where it is to be found.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.