Scientist of the Day - Claude Mellan

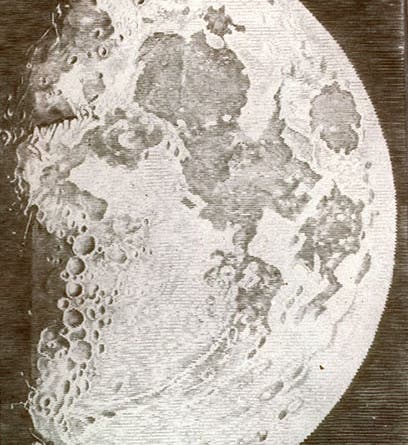

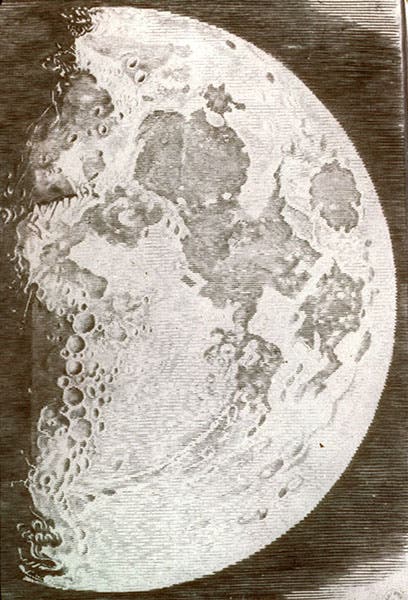

Eight-day old Moon, engraving by Claude Mellan, 1637, Musée Boucher de Perthes, Abbeville, France (Musée Boucher de Perthes, Abbeville)

Claude Mellan, a French artist and engraver, died in Paris on Mar. 9, 1688, at the age of 90! Mellan was a native of Abbeville, in northwestern France, and had studied in Paris for a time before heading for Rome in 1624. He immediately attached himself to the workshop of Francesco Villamena, one of the best artist/engravers of the period, who, incidentally, engraved one of the earliest portraits of Galileo. Villamena had begun to use an engraving style that emphasized long, flowing lines, rather than busy cross-hatching, and Mellan took to it immediately. When Villamena died, Mellan studied with Simon Vouet, another gifted artist, who pursued the same kind of linear style.

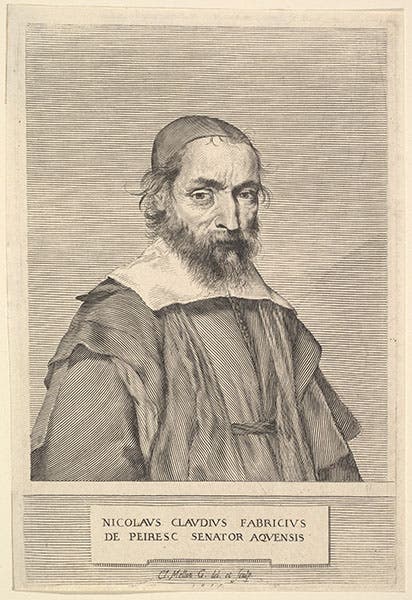

When Mellan set out on his own, around 1630, he pursued this flowing style to its limits, and his virtuosity is well on display in a portrait he did of Nicolas Claude Fabri de Peiresc, the French polymath who has already been the subject of a post in this series. In that post, we showed a later impression of the Peiresc portrait by Mellan that is in our collections; here we show an earlier impression, in better condition, that is in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (third image). Notice how Peiresc’s robe is engraved without cross-hatching.

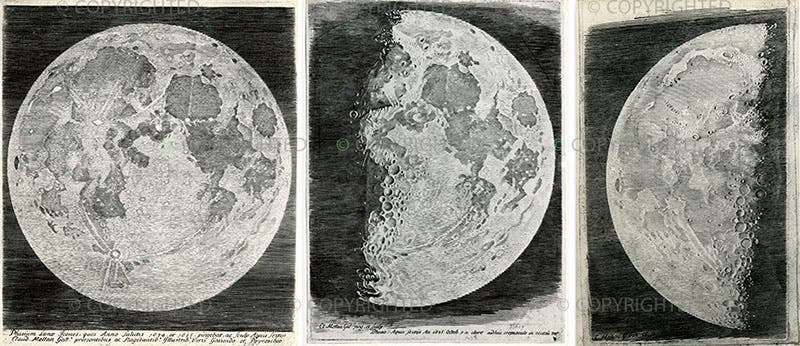

The Peiresc portrait was the outcome of a trip that Mellan made in 1635 to Aix-en-Provence, in southern France, where he visited the home of Peiresc, who happened to be entertaining Pierre Gassendi as a house guest at the time. The two men had just acquired a new telescope (remember, the telescope was still a novelty at the time – it had been only 25 years since Galileo first looked at the Moon with his telescope), and Gassendi and Peiresc were trying to record their impressions of the Moon in drawings, but neither had much artistic ability. When Mellan happened on the scene, they seized Fortune by the forelock and persuaded Mellan to make some lunar drawings using their instrument. This Mellan did, and the engravings that resulted from his drawings are the most vivid impressions of the lunar surface that the world would see for the next two centuries. Unfortunately, most of the world did not see them, since they were never included in a printed book, and only a few sets survive, all of them in France. The Musée Boucher de Perthes in Abbeville has all three engravings, and you can see them here courtesy of the Museo Galileo website (fourth image). Our first image, the engraving of the eight-day-old Moon, was provided directly by the Musée Boucher de Perthes.

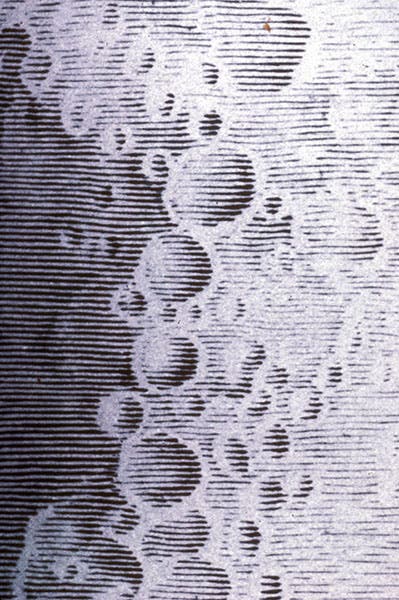

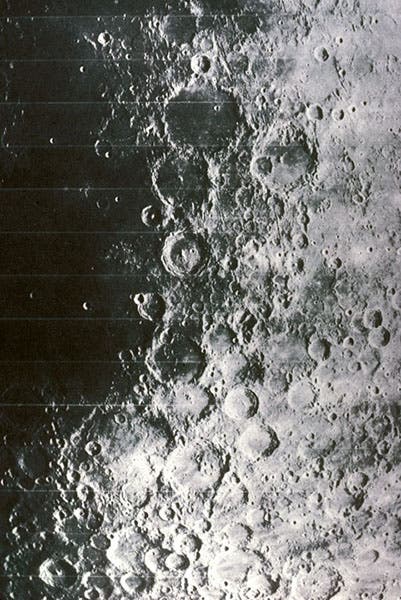

The most amazing feature of these lunar engravings is that all the shading was produced by thickening or thinning the engraved lines; there is no cross-hatching in evidence anywhere. Not only that, all the lines are horizontal. You may think you see outlines of craters and seas, but the outlines are not there. Since there are no details of any of Mellan’s maps available on the web of which I am aware, I include one, which I made from the photograph supplied by the Musée Boucher de Perthes (fifth image). For comparison, I also include a photograph made of the same portion of the lunar surface by Lunar Orbiter IV in 1967, taken from a hundred miles away (sixth image). The similarity is stunning.

The lunar highlands, photograph by Lunar Orbiter IV, 1967, for comparison with Mellan’s engraving of the same area (nasa.gov)

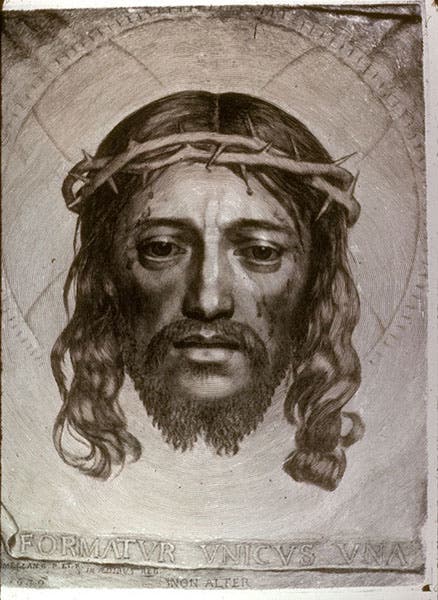

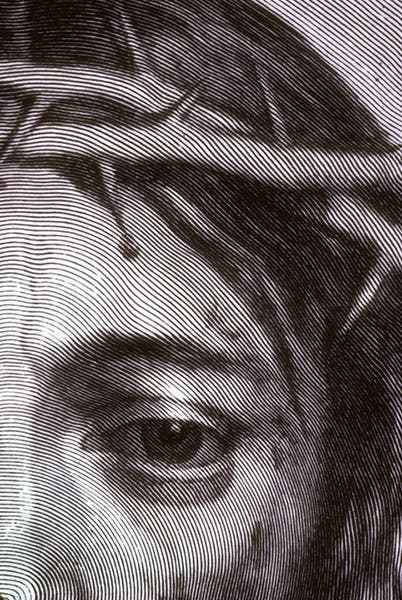

Mellan’s engraving technique was one that that few could master, and some years later, he decided to flaunt his skill. In 1649, he engraved the "Veil of Veronica" or the “Sudarium,” a depiction of the face of Christ, and the entire image is produced by a single engraved line, which starts at the center, and spirals out, swelling and thinning as it goes. This engraving is relatively easy to find, as many copies survive – one of them is in the print collection at the nearby Spencer Museum of Art in Lawrence (seventh image). It is indeed an amazing tour-de-force. So that you can better appreciate the skill of Mellan, I also provide a detail from a photograph of the Spencer Museum print (eighth image).

Sudarium, engraving by Claude Mellan, 1649, Spencer Museum of Art, Lawrence, Kansas (spencerart.ku.edu)

Detail of Sudarium, engraving by Claude Mellan, 1649, showing Mellan’s swelling-line technique of shading, Spencer Museum of Art, Lawrence, Kansas (spencerart.ku.edu)

I had the good fortune to see all three Mellan lunar engravings many years ago, when I attended a Gassendi conference in Digne, and the organizers had borrowed the Mellan maps from Abbeville for the occasion. They are not very large, but they are truly stunning. I have also seen the “Veil of Veronica” print firsthand in Lawrence, and it is impressive and unforgettable, but it is still just Mellan showing off. His lunar maps, however, use his novel technique for a demonstrable purpose, to recreate the impression of looking at the Moon through a telescope, and he succeeded beyond all expectations. His engravings are the best depictions of the Moon made before 1834, and hardly anyone even knows they exist.

There are several engraved portraits of Mellan, but sadly, no self-portrait engraved in his unique style. The portrait we show here (second image) is one in our collections, included in Charles Perrault, Les hommes illustres (1696-1700).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.