Scientist of the Day - Cornelius Vanderbilt and the Lexington

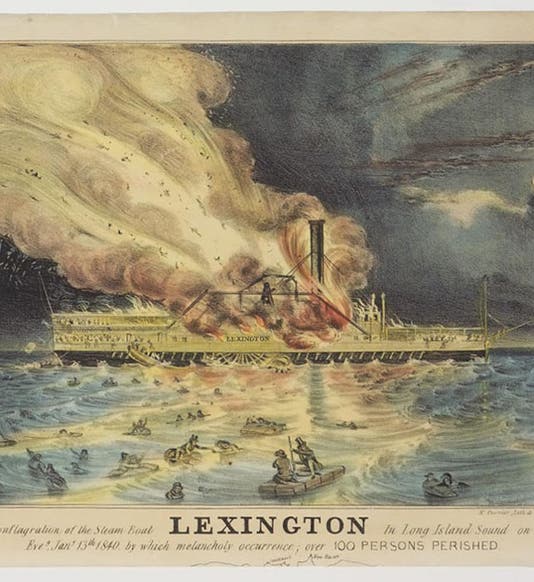

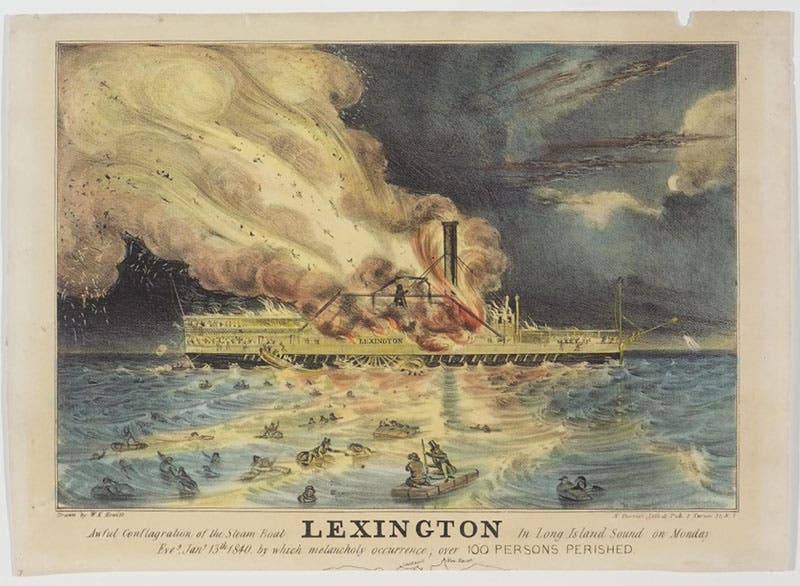

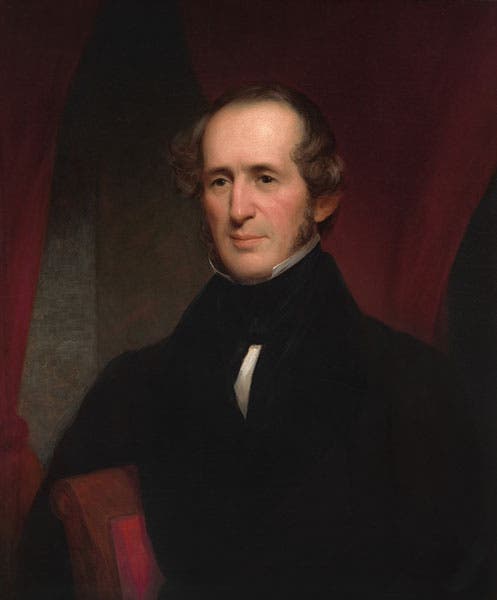

The Lexington was a paddlewheel steamboat, commissioned in 1834 by Cornelius Vanderbilt, at that time an American steamboat magnate. On Jan. 13, 1840, the Lexington caught fire off Long Island, burned and sank, resulting in the death of 139 passengers and crew in one of the early tragic steamboat disasters in the United States. Its demise was captured in one of the first best-selling hand-colored lithographs issued by Nathaniel Currier (first image).

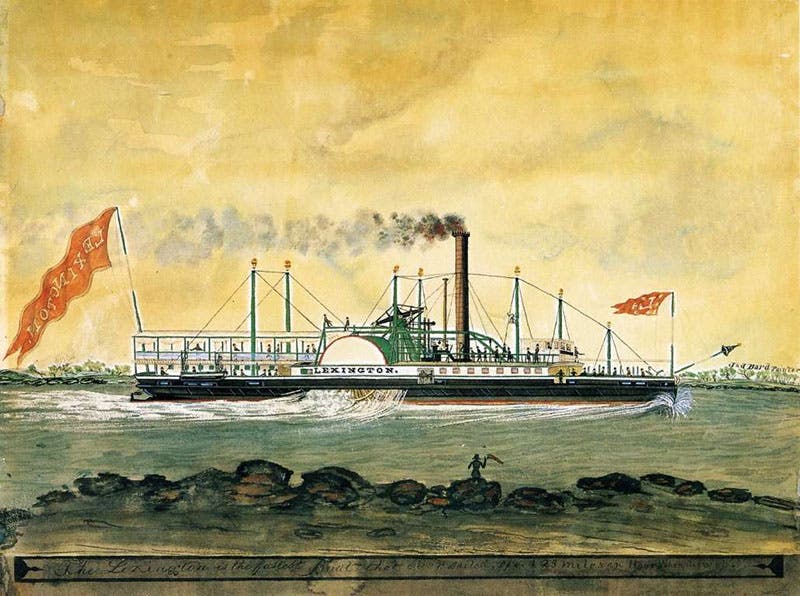

Vanderbilt intended the Lexington for luxurious passenger travel between New York and Providence. It had beautiful teak and brass fittings on its deck and a sumptuous lounge to accommodate wealthy passengers. You can see it in all its pre-disaster finery in an undocumented watercolor below (third image). But in the late 1830s, Vanderbilt’s interests switched to, or rather expanded to include, railroads, and he acquired the Boston Providence railroad, which at the time had its western terminus in Stonington, Connecticut, on Long Island Sound. So Vanderbilt changed the destination of the Lexington from Providence to Stonington, so that travelers from New York to Boston could catch the train in Stonington. And then he sold the Lexington to private operators, who upgraded the engine from wood-burning to coal-burning, but did not otherwise allow for the fact that coal burns hotter than wood.

In the early evening of Jan. 13, 1840, the Lexington was about 4 miles off the northern coast of Long Island, headed to Stonington, when the disaster began. The seas were rough, the engine was under stress, and the wooden casing around the smokestack began to smolder. The crew made no immediate attempt to wet down the casing, and instead went to check on the engine. There was a cargo of about 150 cotton bales piled up near the smokestack (not what one would expect to see on a luxury passenger boat), the cotton caught fire, and the flames spread to the rest of the boat. The Lexington carried three lifeboats, but the crew apparently did not know now to deploy them. The first lifeboat was carried into the paddlewheel and destroyed, killing everyone on board, including the captain (why the captain was in the first lifeboat launched is a good question that no one seems to have asked). The other two lifeboats were dropped stern-first into the water and sank immediately. So passengers and crew were forced by the growing inferno into the frigid sound, where most of them perished. The only 4 survivors rode cotton bales or flotsam to eventual rescue.

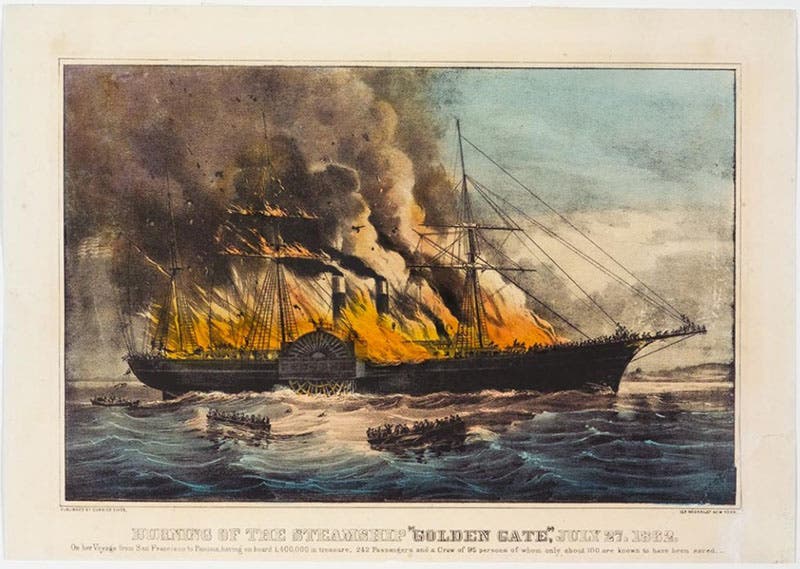

Steamboat disasters were not infrequent in the decades of the 1840s and 1850s. Sometimes steamboats ran afoul of snags, especially on the Mississippi River; sometimes they caught fire; and more than occasionally, their boilers exploded. Boiler explosions were the most dramatic, since often the steamboat would be violently blown apart, along with the passengers. But maritime disasters were just what Nathaniel Currier needed to generate lithographs that would appeal to a paying audience. Awful Conflagration of the Steam Boat Lexington in Long Island Sound, on Monday eveg, Jany. 13th 1840, by which melancholy occurrence; over 100 persons perished, as the print was titled (first image), was published by Nathaniel Currier (not yet allied with James Ives) in 1840, and no doubt sold thousands of copies (although to my knowledge there are no records of imprints sold). It proved to be a formula for publishing success, as later prints attest: The Burning of the Steamship Austria, 1858, and The Burning of the Steamship Golden Gate, 1862. We show the latter print here (fourth image), since the Lexington and Golden Gate were similar-looking side-wheelers. Not all of the Currier and Ives prints depicted disasters, as you will see if you look at our most recent post on Currier, and at a post before that. But even there, you will see another ship sinking, and a building burning. Then, as now, disasters sell!

I should note that a book was published just last fall about the Lexington disaster, called Death by Fire and Ice: The Steamboat Lexington Calamity, written by Brian E. O'Connor and published by the U.S. Naval Institute Press. I have not seen a copy and the library does not own it. But it might well have answers to some of the questions we raised, and I will check it out once the book makes its way to my desk.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.