Scientist of the Day - Daniel Kirkwood

Daniel Kirkwood, an American astronomer, was born Sep. 27, 1814. He joined the faculty at Indiana University in 1856 as professor of mathematics, and he spent most of the next thirty-five years there, until he moved on to Stanford University in 1891, when he was 77 years old. Kirkwood's claim to fame came about as a result of his study of asteroid orbits. The first asteroid was discovered in 1801; three more turned up in the next 6 years, and then no more were discovered until nearly 40 years later, when a fifth was sighted in 1845.

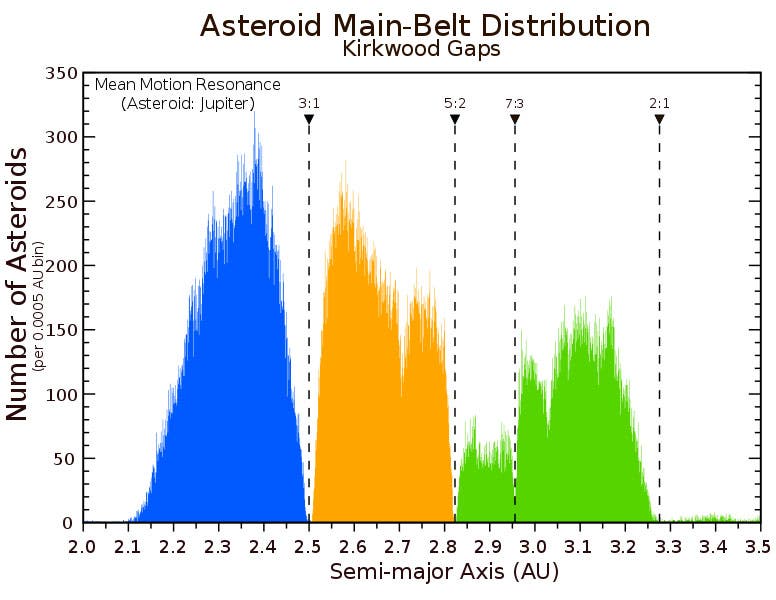

All of the discovered asteroids lay in the broad space between Mars and Jupiter, in what is now called the asteroid belt. They all lie near the ecliptic, which is to say, the plane that passes through the Earth's orbit and the Sun, but they move quite independently, so their distances from Earth vary, as do the eccentricities of their orbits, and their speeds, so it would be quite a mess out there if the space they occupy were not so huge. Most of the orbits of the known asteroids were worked out within a few years after their discovery, once they were recovered after passing behind the Sun, and these orbits were what intrigued Kirkwood. He found that there were gaps in the distances of asteroids from the Sun.

For example, there are no asteroids 2.5 astronomical units from the Sun (an astronomical unit, or au, is about 93 million miles, the average distance of the Earth from the Sun). Nor are there any at 2.1, or 2.8, or 3.25 au. Kirkwood not only noticed this, he figured out why these gaps exist. An asteroid at 2.5 au would orbit the Sun in just under 4 years, or exactly 1/3 the time it takes massive Jupiter to orbit the sun. We would say that such an asteroid would be in 3:1 resonance with Jupiter, which means it would feel a strong gravitational tug from Jupiter three times in its annual orbit, and would be displaced. The other gaps (we call them Kirkwood gaps) would be in orbital resonances of 4:1, 5:2, and 2:1. Jupiter clears out these gaps with its enormous gravitational pull.

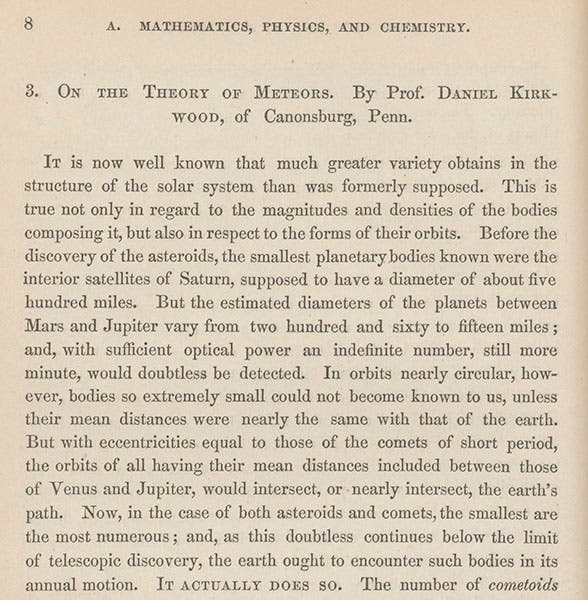

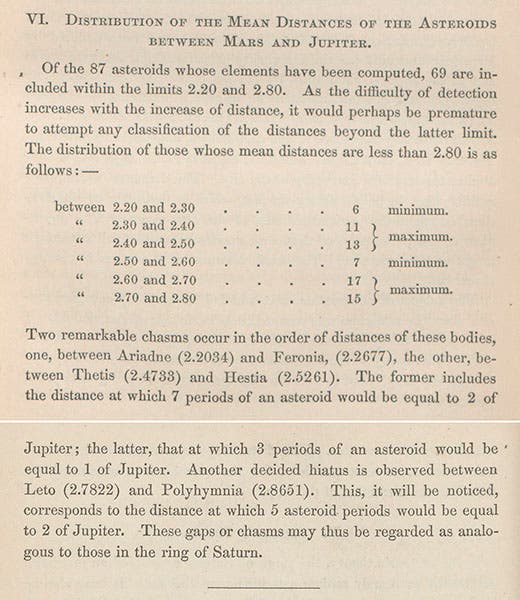

Kirkwood announced the existence of Kirkwood gaps and his explanation in an article in the Proceedings of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in 1866; we show here the first page of the article and an extract from the text. In the same paper, he suggested (correctly) that the gaps in the rings of Saturn might be caused by resonance with some of the satellites of Saturn.

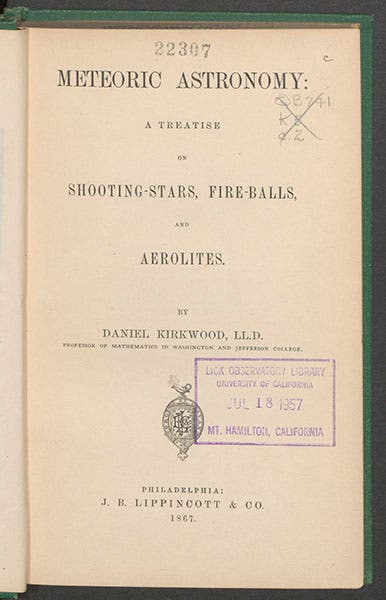

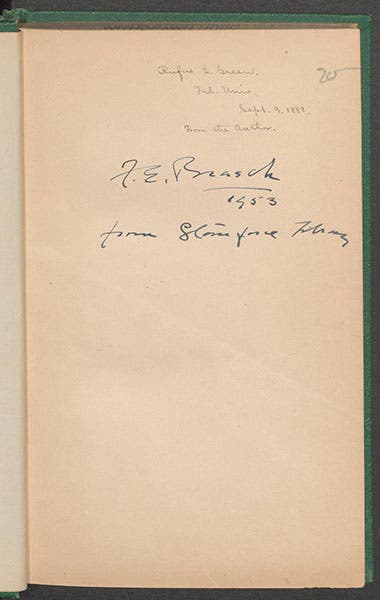

Kirkwood published three books in his lifetime; we have one, Meteoric Astronomy (1867; fifth image). Our copy is interesting for its contents but even more so for its provenance. It was given by Kirkwood to Rufus L. Green, professor of mathematics at Indiana, and the book is so inscribed on an endpaper (sixth image). Green moved on to Stanford University when it was founded, and taught Herbert Hoover. We might guess that Green lured Kirkwood to Stanford as well. After Green's death, the book came into the possession of Frederick E. Brasch, a famous collector of Newtoniana, a collection that he later gave to Stanford. His signature is right below Green's, dated 1953. Then the book was acquired by the Lick Observatory Library, and its stamp is on the title page. The book then somehow escaped Lick Observatory and entered the library of the University of California, Santa Cruz, and was withdrawn by them; their stamp is on another endpaper. The book was subsequently acquired by a private collector and later given to us. We intend to keep it.

Most of Kirkwood’s papers and effects are in the archives of Indiana University, who also own one of the few portraits of our astronomer of the day (first image).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.