Scientist of the Day - Davidson Black

Davidson Black, a Canadian physician and anatomist, was born July 25, 1884, in Toronto. After getting his medical degree, he workd for a year with Grafton Elliot Smith in Manchester, who was actively studying the newly discovered Piltdown fragments, and Black soon developed an interest in human fossils. In 1919, Black took up a faculty position at the Peking Union Medical College in China, where he taught embryology, physiology, and anatomy. Around 1925, he decided he wanted to look for human fossils in China, and he learned that several investigators had discovered what they claimed were ancient human teeth at a site called Dragon Bone Hill at Chou Kou Tien (now Zhoukoudian), in southwestern Peking (now Beijing). Black identified the teeth as prehuman, and he used them to secure a grant to excavate further from the Rockefeller Foundation in the United States. One of the people working at Zhoukoudian in those days was, incidentally, Teilhard du Chardin, the French Jesuit priest, who appears in the group photograph taken in 1929 (second image)

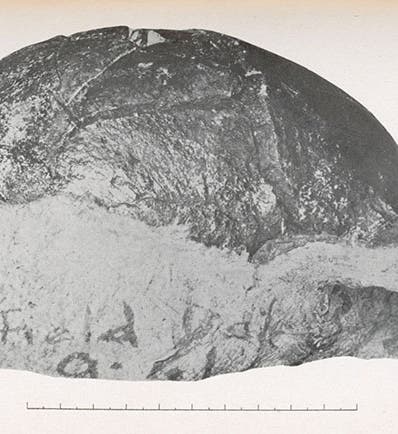

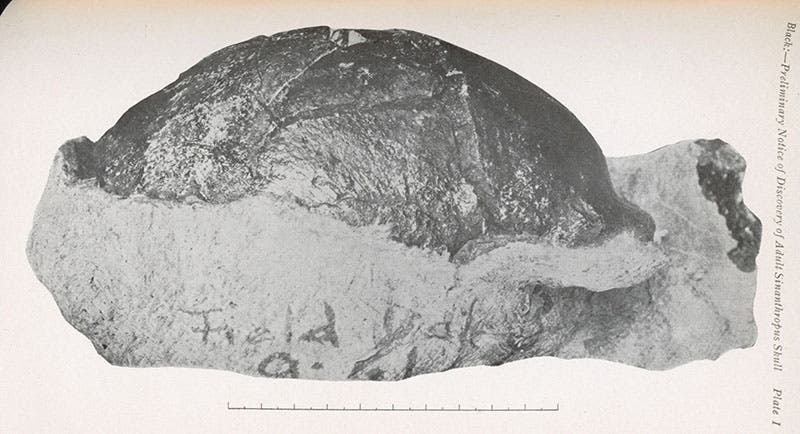

By 1927, Black was convinced that the teeth, now numbering five, belonged to an extinct human genus, which he named Sinanthropus. His claim was met with considerable skepticism, and he knew that he need to find some additional cranial remains to establish his new genus. He was also having problems with the Medical College, whose administrators were not sure what business their professor of anatomy had looking for prehistoric human remains. Fortunately for the fate of Sinanthropus, a part of a was found in 1928. And then, on Dec. 2, 1929, Black’s most promising young Chinese investigator, Pei Wenzhong (often referred to as W.C. Pei in English publications), uncovered a skullcap in one of the caves at Dragon Bone Hill. He managed to remove it, still in its matrix, without having it fall to pieces, and when he presented it to Black three days later, Black knew that Sinanthropus was here to stay. He published a description and a picture of the skull in the Bulletin of the Geological Society of China in 1929, a journal that we have in our Library (first and third images). He gave full credit to Pei, then and always, for finding the skull, but Black is still often referred to as the discoverer of Peking Man, as the genus came to be called. In fact, Pei discovered it; Black identified, described, and named it.

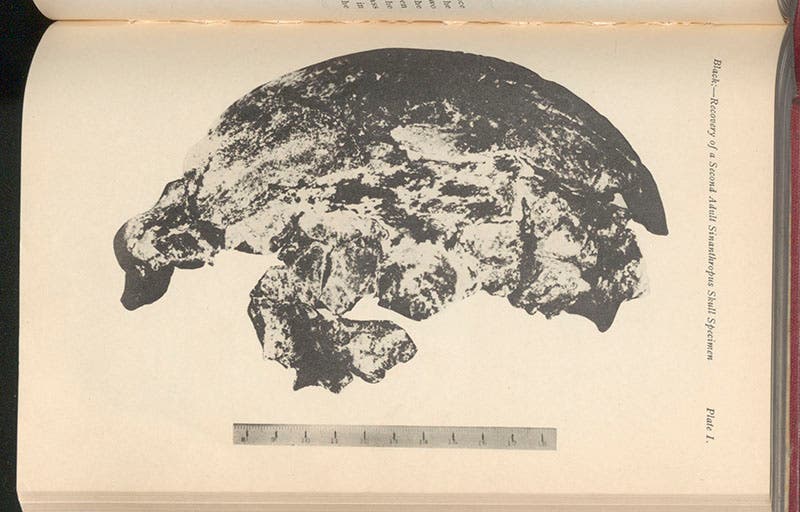

The next year, Pei was able to reconstruct a second skull from fragments that had been recovered in previous excavations (fourth image). When put together, it was the same shape and size as the first, establishing Sinanthropus as a valid and consistent human type, further vindicating Black’s creation of a new human genus. Its full name, by the way, is Sinanthropus pekinensis, although we now refer to it as Homo erectus pekinensis.

More fossils were found in the next four years. Black used some of his Rockefeller Foundation funds to establish the Cenozoic Research Laboratory to supervise the excavations. The Lab was positioned within the Peking Union Medical College, which probably allowed Black to keep his position there. Black suffered a heart attack when he was 49, and knowing that his father had died of a heart attack at a similar age, he probably knew how the wind was blowing. But he kept working long hours at the College, and on the evening of Mar. 15, 1934, while studying one of the Peking Man fossils in his office, he quietly died of heart failure. He did not quite make it to age 50.

None of the fossils that he and Pei recovered between 1926 and 1934 survive. When the threat of a Japanese invasion loomed prior to World War II, it was decided to make replicas of the specimens and convey the originals back to the United States for safekeeping. The Sinanthropus fossils were carefully crated up and shipped to the coast, where an American ship was waiting to transport them to safety. Unfortunately, the date for the transfer was, in hindsight, ill-chosen: it was just before Dec. 7, 1941. All hell broke loose in the Pacific, and the crates of fossils were lost. Even if they had made it on-board ship, they would still have perished, for the ship was sunk in the aftermath of the attack on Pearl Harbor. To this day, the fossils have never turned up. Fortunately, the site at Zhoukoudian was reopened after the War, and many new specimens of Peking Man were recovered. But of the original skullcap and jaw fragment, the type specimens that established the genus, as well as the additional skulls found later, we have only replicas of the casts that were made before 1941 (fifth image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![Andromeda and Perseus, constellations figured by James Thornhill, with star positions determined by John Flamsteed, in Atlas coelestis, plate [15], 1729 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/1b30cfec-5be6-4297-a7fb-97255ba992e5/thornhill1.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)