Scientist of the Day - Edward Wotton

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

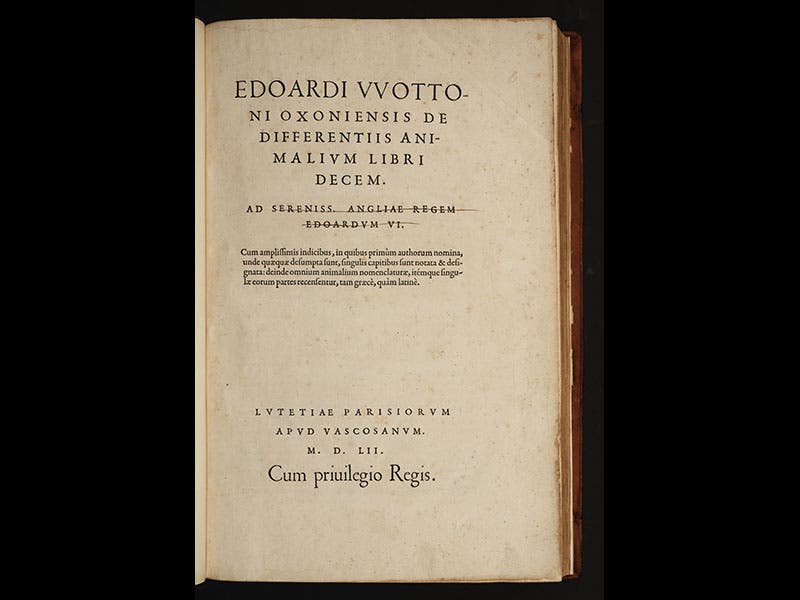

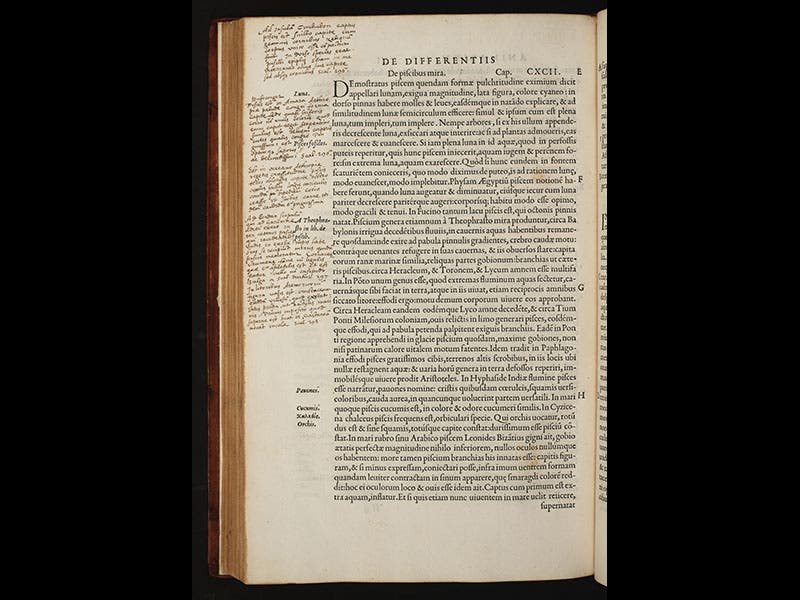

Edward Wotton, an English classical scholar, died Oct. 5, 1555, at the age of about 63. In 1552, Wotton published De differentiis animalium libri decem (Ten books on the differences between animals), the first printed work of natural history by an Englishman (although the language of the book is Latin). De differentiis animalium discusses mammals, birds, fish, insects, and sea creatures, but it was written, as far as anyone can tell, entirely in the library, without a single reference to a field observation. Instead of looking at nature first-hand, Wotton read the likes of Pliny, Aristotle, Dioscorides, and Oppian, classical authors all, and drew the contents of his natural history from theirs.

We use the term "humanist natural history" to refer to this kind of an approach to nature, guided by the belief that ancient authorities had discovered everything worth knowing, and the best we moderns can do is resurrect ancient texts, re-organize them if it pleases us, and make their observations our own. There was nothing wrong with Wotton's humanist attitude; scholars in many disciplines at this time were looking to antiquity for guidance. But Wotton had the ill fortune to send his book to the press in Paris at the very time that Conrad Gessner was publishing his Historia animalium (1551-58) in Zurich, a work that was also humanist in orientation, but which was ten times as large as Wotton's, and richly illustrated with woodcuts of the animals being discussed. Wotton had no illustrations at all in his book. So Wotton was rapidly eclipsed by Gessner, even in England.

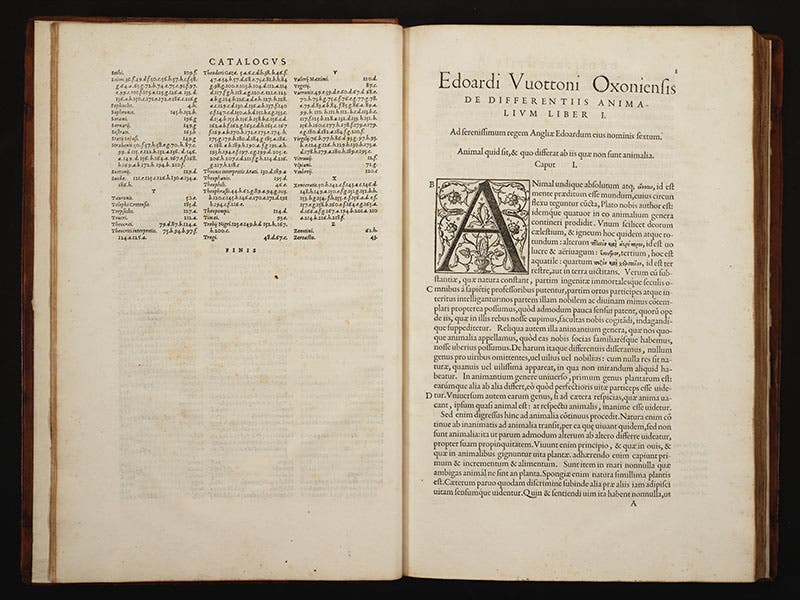

Once you get over the fact that Wotton’s book lacks woodcuts, and you look at it without any expectations, you realize that, even without pictures, this is a very handsome publication—well printed and nicely laid out, with handsome type fonts, especially the Italic. The printer was Michael Vascosanus, and we have three more of his imprints in our History of Science Collection—by Julius Caesar Scaliger, Oronce Fine, and Jean Pierre de Mesmes—each of them just as handsome as the Wotton. In fact, the owner of our copy of Wotton appears to have owned the Scaliger as well, for our copy contains a number of annotations referencing Scaliger’s book (fourth image).

Historians of the scientific book tend to fixate on printers such as Erhard Ratdolt of Venice and Johannes Petreius of Nuremberg, but Vascosanus would also be a scientific printer well worth collecting and studying.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.