Scientist of the Day - Edward Wright

Edward Wright, an English mathematical practitioner, was baptized Oct. 8, 1561 (the only sure date we have for Wright). "Mathematical practitioner" is a term applied to those in early modern Europe who used their knowledge of mathematics to design or construct precision instruments or maps. Wright employed his considerable mathematical skills to make the new Mercator projection available to cartographers.

Gerard Mercator had introduced his new world map in 1569, and it was a navigator's dream, since in order to get from point A to point B, you simply had to plot both points onto the Mercator map, connect them with a straight line, measure the angle that the line makes to a line of longitude, and head off in that direction on your compass. The Mercator projection was the only map projection at that time that had this property, that compass lines, called rhumb lines or loxodromes, are straight lines. On all other projections, rhumb lines curve about in a complicated manner.

The only problem for cartographers who wanted to use this new projection is that Mercator did not explain how he did it. If you don't know how to space the latitude lines (they get further apart in a precise manner as you go north or south from the equator), then the rhumb lines will not be straight. So Mercator’s' 1569 map stood alone for 30 years (except for a multitude of botched copies). In the early 1590s, Wright discovered the mathematics behind the Mercator projection. Not only did he derive a formula for calculating the distance of the latitude lines from the equator, he laboriously produced a table that solved his formula for every minute of arc from 0° to 90°. You can plot the grid lines for a Mercator map directly and easily from this table, and you can also determine exactly where you should place any town or coastline, if you know the latitude, you just look up its equatorial distance on Wright’s table.

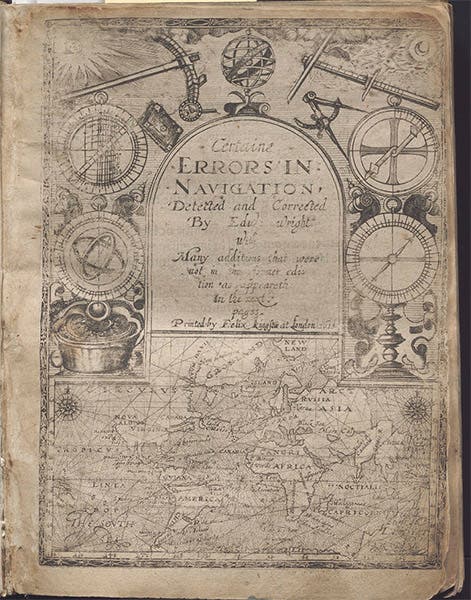

After several cartographers borrowed his unpublished tables and used them without his permission, Wright decided to put them into print. In 1599, he published Certaine Errors in Navigation, which contains an abbreviated form of his table, providing equatorial distances for every 10 minutes of a degree. It is a milestone book in the history of navigation and cartography. He reprinted it 11 years later, in 1610, this time with the full table (second image). It was reprinted again in 1657, and this is the only edition that ever comes on the market. Even though it is a third edition, it still brings astronomical prices.

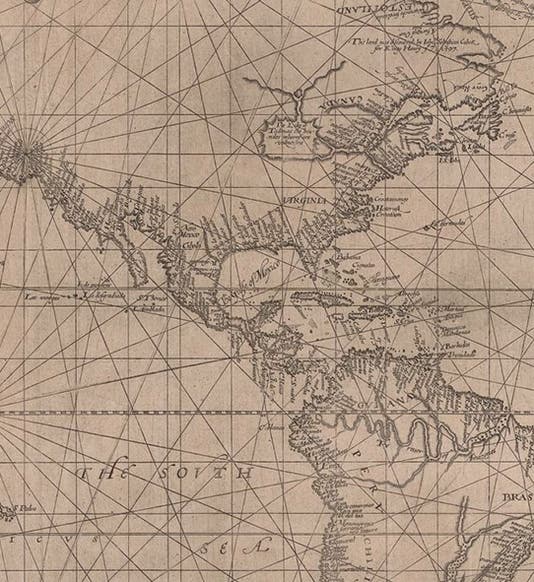

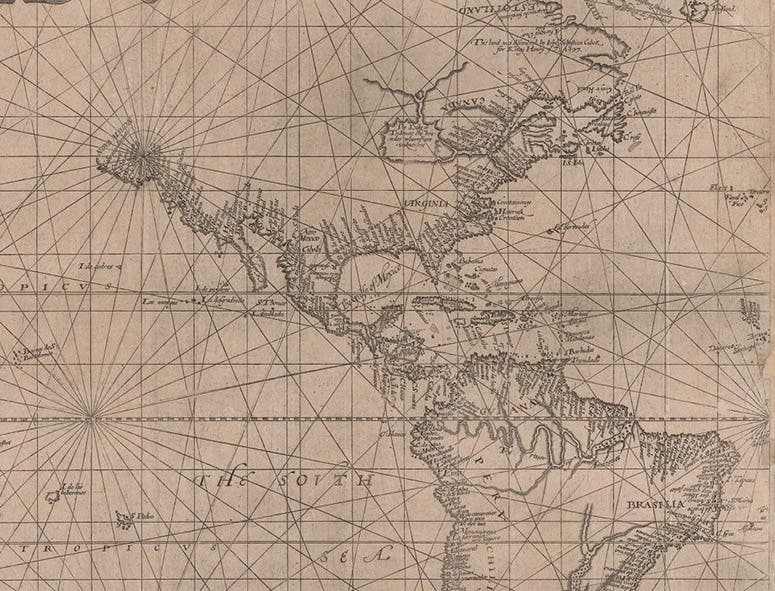

Wright may be even better known for the world map he designed in 1599, which was included in volume 2 of Richard Hakluyt’s Principal Navigations. This was only the second world map published using the Mercator projection, and it corrected many errors in Mercator’s original map. Wright used cartographic information from Emery Molyneaux’s terrestrial globe of 1592, so it is often referred to as the Wright-Molyneaux world map. We show a copy of the original map (24” by 17” on two sheets; third image), courtesy of the New York Public Library (here is the link), as well as a detail of that map (first image). There is another copy at the John Carter Brown Library in Providence. Both are worth looking at, and on both sites, you can zoom in almost indefinitely to see all the detail you might want.

The Wright-Molyneux map does not really have a proper title, sometimes it is referred to by the description in the cartouche near Africa: Thou hast here, gentle reader, a true hydrographical description of so much of the world as hath beene hetherto discouered and is comne to our knowledge. But this was obviously not intended to be a title, so the “Wright-Molyneux World Map” is nearly everyone’s working label.

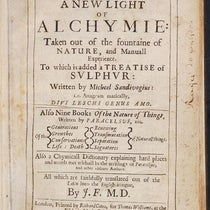

We have a facsimile of Wright’s Certaine Errors in the Library, and a facsimile of the Wright-Molyneux 1599 map, but we do not have original editions of either, and we are unlikely to ever obtain them, as both are highly prized cartographic treasures. Wright was later – not surprisingly – one of the first to recognize the value to mathematicians of John Napier’s invention of logarithms (1614), and he immediately set out to translate Napier’s Latin book into English. He finished, but died in the process in 1615, and his translation was only published after his death. We have original editions of all three of Napier’s books in our collections, but not Wright’s translation.

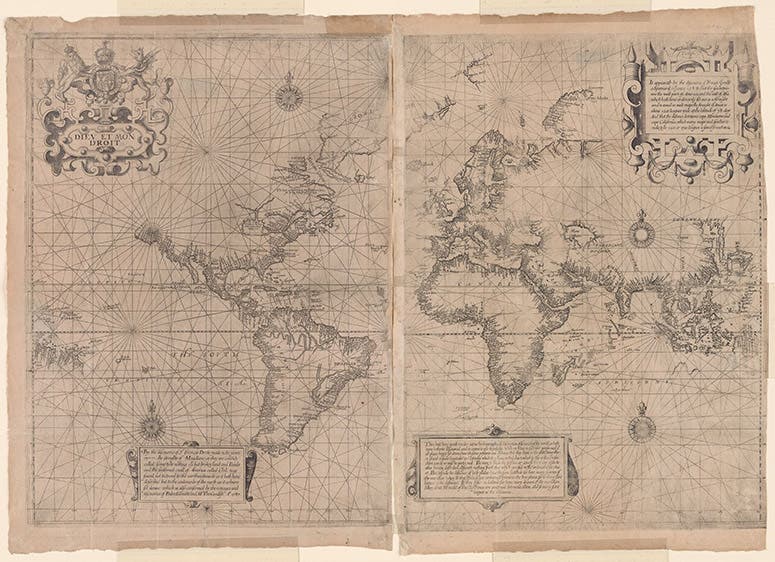

We do have one original publication of Wright, a three-page appendix he contributed to Thomas Blundeville’s The Theoriques of the Seven Planets (1602), explaining how to determine one’s latitude by measuring the magnetic declination and referring to a short table that Wright provided. It’s not much, but it is all we have. We show you the first paragraph of the appendix, with Wright’s name in evidence (fourth image).

We cannot even show you Wright’s portrait, since none exists. But we hope you remember him. If the Mercator projection is a household word – and surprisingly, it is – we have Edward Wright to thank.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.