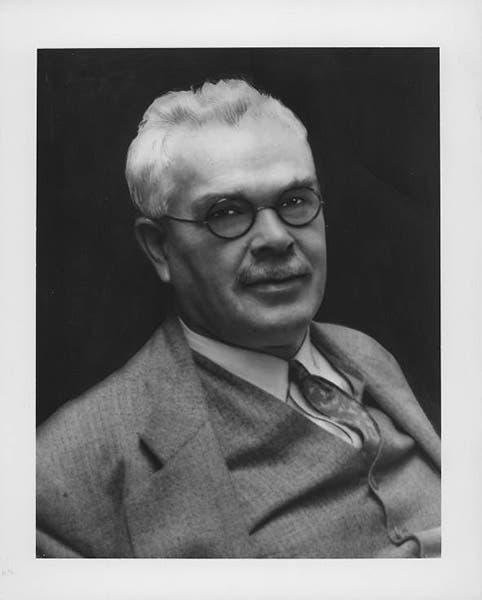

Scientist of the Day - Francis Pease

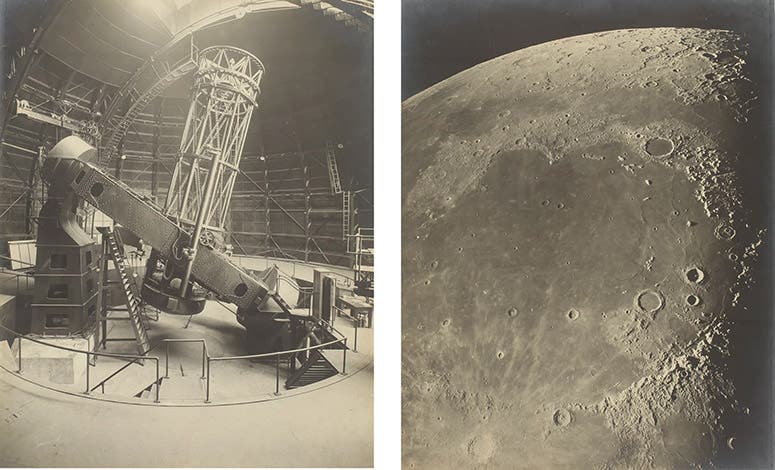

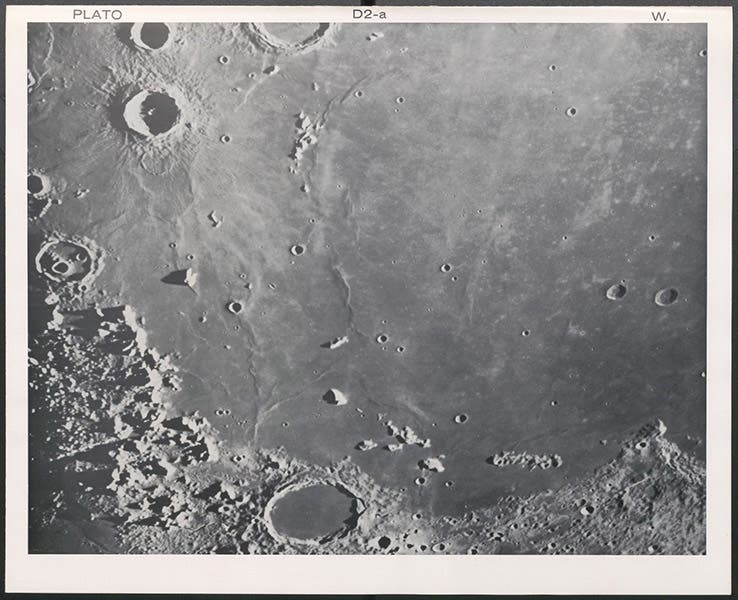

The lunar crater Plato and the Mare Imbrium (Sea of Rains), photograph taken by Francis Pease with the 100-inch Hooker telescope, Sep. 15, 1919, in Photographic Lunar Atlas, by Gerard P. Kuiper, 1960 (Linda Hall Library)

Francis Pease, an American mechanical engineer, astronomical instrument maker, observatory designer, and photographer, died Feb. 7, 1938, at the age of 57. Pease had been working at the Yerkes Observatory north of Chicago when he was hired by George Ellery Hale in 1904 to help set up the new Mount Wilson Solar Observatory in Pasadena, California. Pease played a significant role in designing and overseeing the construction of what were, at the time they were built, the world's largest operating reflecting telescopes, the 60” reflector, opened in 1908, and the 100-inch Hooker reflector, which saw first light in 1917. Pease does not get much credit for his design work – look up either telescope on Wikipedia and you will find no mention of Pease – but it seems to be commonly agreed that his contribution to all of Hale’s enterprises was essential. It was not so much the optics of the telescopes that he worked on, but everything else. It was Pease, for example, who had to figure out how to get the 60-inch telescope up the mountain (third image), and then later, the mirror for the 100-inch reflector. Pease also devoted much of the last eight years of his life to working on the design of the 200” telescope at Mount Palomar, completed after his death, for which he also gets little credit.

Fortunately for his legacy, Pease also used the telescopes he designed with uncommon skill, and for this he is remembered. One of the regular visitors to Mount Wilson was Albert Michelson, who many years earlier had used an interferometer to try to measure the speed of the Earth through the ether. An interferometer is an optical device that utilizes the principle that two light beams that travel different distances will interfere with each other, resulting in light and dark fringes of light that are measurable. The distance between the fringes will reveal the difference in light path. The earlier interferometer experiment had failed to detect any changes in path length as the instrument was rotated with respect to the ether, suggesting that perhaps there was no ether, which turned out to be a significant negative result.

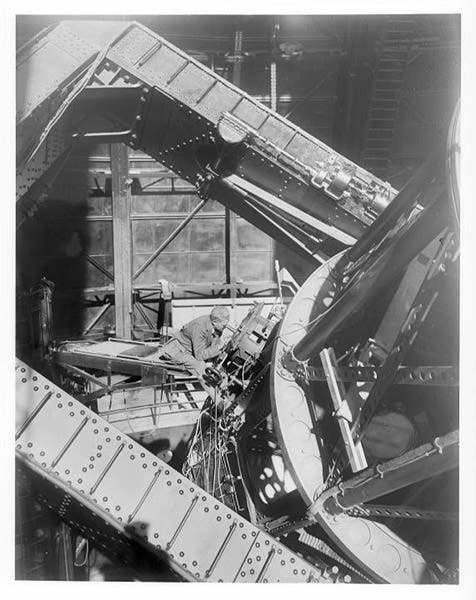

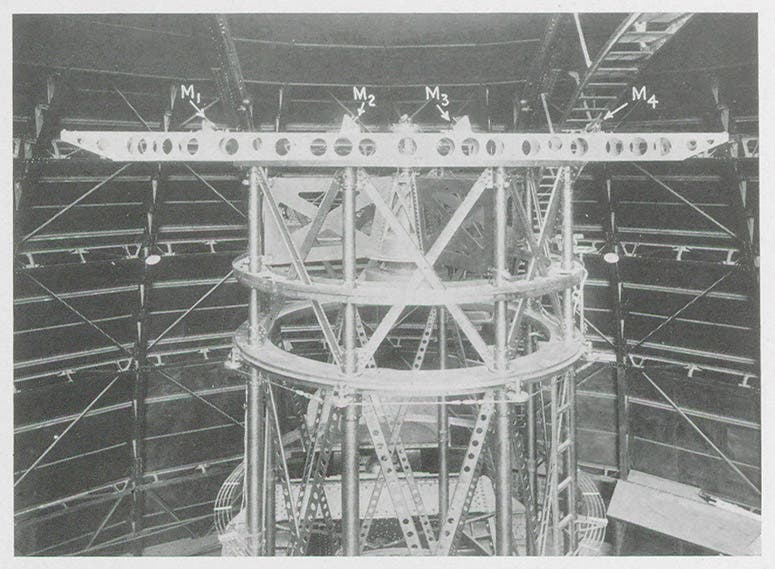

But the idea in 1920 was to use an interferometer to measure the diameter of a star. Light coming from a star that is very large should travel different distances, depending on whether it comes from the edge or the center of the star, and should therefore produce interference fringes in an interferometer. Pease built a 20-foot interferometer, and they affixed it to the front of the 100-inch Hooker telescope. Their target was alpha Orionis, also known as Betelgeuse. Their premise turned out to be a good one. They measured the angular diameter of Betelgeuse to be 0.047" of arc. Depending on one's calculation of the distance to Betelgeuse, this corresponds to a diameter of at least 240 million miles (our Sun is about 1 million miles across). Pease and Michelson jointly published an article in the Astrophysical Journal in 1921 in which they announced their results, and, just for us, included a photograph of the interferometer in place, with the four mirrors designated by the letters M1-M4 (fourth image).

The Pease-Michelson 20-foot interferometer affixed to the front of the 100-inch Hooker telescope, plate accompanying a paper by Albert Michelson and Francis Pease in Astrophysical Journal, 1921, vol. 53, 1921 (Linda Hall Library)

But perhaps the astronomical art in which Pease was most skilled was lunar photography. In 1919 and 1920, he took dozens of photographs of the Moon with the new 100-inch telescope, and they were the most detailed lunar photographs ever recorded. It wasn’t just that Pease had access to the finest telescope in the world, which he did. But many people used the 100-inch for astronomical photography, and no one demonstrated the skill and tracking ability and mastery of exposure that is evident in Pease’s work. In 1931, Walter Goodacre published The Moon, with a Description of its Surface Formations, and he included among all his maps a Pease lunar photograph, grandly claiming that it showed details that "probably are now rendered visible to the human eye for the first time in the history of the race." We displayed Goodacre's book, open to Pease's photograph, in our exhibition The Face of the Moon, and we include the photograph here as well (fifth image).

The southern lunar highlands, photograph taken by Francis Pease with the 100-inch Hooker telescope, Sep. 15, 1919, in Walter Goodacre, The Moon, with a Description of its Surface Formations, 1931 (Linda Hall Library)

In 1960, Gerard Kuiper published his Photographic Lunar Atlas, a collection of the best existing lunar photographs, which essentially mapped the lunar surface. For this collection, Kuiper selected 31 plates from the Mount Wilson archives, all of them taken by Pease, and 13 of those were recorded in just a four-day span from Sep. 12 to Sep. 15, 1919. This means that, in Kuiper's opinion, no one had taken any better plates of those sectors of the Moon in the succeeding 40 years. We show one of the photographs chosen by Kuiper here (first image), depicting the region around the crater Plato, which is on the northern edge of the Mare Imbrium (Sea of Rains) near the top (north) of the moon. The detail is exquisite, and we can understand why Kuiper wanted to bypass 40 subsequent years of lunar photography to snatch this relic of 1919 for his atlas.

Pease also recorded many fine photographs of nebulae, which we must pass over here, and he also constructed a 50-foot interferometer for Michelson, who died before it could be put to use. It is a shame that Pease’s early death precluded his seeing at Mount Palomar the realization of his dreams for a 200-inch telescope. He died in Pasadena and must be buried somewhere, but I am unable to discover the location of his grave.

In 2017, two Pease photographs were sold at auction at Sotheby’s. I thought I would reproduce them here (seventh image), for they make an unexpected but richly appropriate pair. The photo on the left shows the 100-inch telescope that Pease helped design and that he used for his lunar and nebular photography. The one on the right captures the entirety of the Moon’s Mare Imbrium, which includes in its sweeping scope the much smaller area pictured in our first image, taken by Pease on the very same night of Sept. 15, 1919.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.