Scientist of the Day - François Blondel

Nicolas-François Blondel, a French architect and mathematician, was baptized June 15, 1618. Blondel spent the first part of his career as a diplomat and tutor, before entering military service, where his forte was fortifications, which he studied wherever he travelled. He had considerable mathematical skill, and in the 1660s he turned to architecture, which he approached mathematically. He was invited to join the Paris Academy of Sciences in 1669, where he joined Claude Perrault, the anatomist-architect, with whom he would develop a great rivalry, especially on matters of architectural theory.

We have two works by Blondel in our collections. The first is an architectural treatise, Resolution des quatre principaux problèmes d'architecture, which was included in an early Academy of Sciences publication, Recueil de plusieurs traitez de mathématique (1676). This is a beautiful folio volume, bound in gilt-lined red leather with the Royal seal on the front cover. Blondel's treatise, which is the first work in the compilation, dated 1673, has wonderful headpieces, as do most of the Academy publications of their first decade. These headpieces were executed by the Academy engraver, Sébastien Le Clerc, who also did the frontispiece for the volume. We do not include it here, but it is a very famous engraving that was included in several Academy publications, including one by Perrault. You can see it at our post on Le Clerc.

One of the problems considered by Blondel in his Resolution was that of constructing columns with the proper swelling in the center to conform to classical models. Blondel invented, or rather revived and improved, a heroic compass, often called Nicomedes' compass, after the originator of the idea, in which the taper could be laid out in a single unbroken line. This required a very large compass. You can see it, first on a piece of paper, held by Architectura in one headpiece (first image), and then in use, wielded by ambitious putti, in another headpiece (second image).

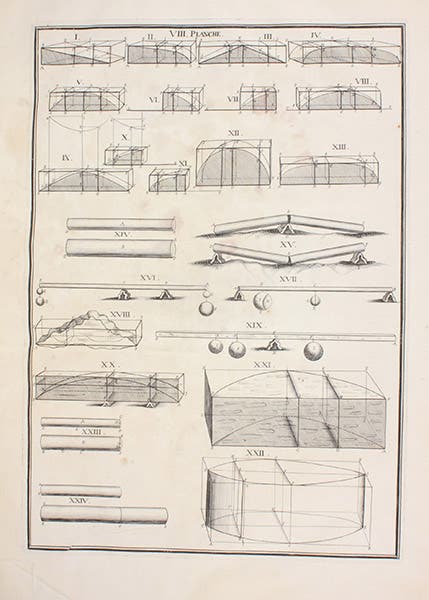

Another problem considered by Blondel concerned the design of horizontal beams so that they did not break in the middle. Galileo, whom Blondel greatly admired, attacked the problem, and almost solved it, suggesting that horizontal beams should have a parabolic form, to make them thicker in the center. Blondel corrected Galileo by showing that an ellipsoidal shape would distribute the load more evenly. There is an engraved plate in his Resolution that addresses the load on horizontal beams with multiple figures (third image).

Blondel wielded his architectural theory at a time when architects were still trying to separate themselves from the tradition of medieval masonry, where architecture was a craft. His idea that the architect should be a mathematician and scholar first, and a constructor of buildings second, was still very much a minority opinion in 17th-century France. The headpiece to the fourth and last problem shows his vision of the architect, alone in his study, in a pensive mood, oblivious to all the practical activity going on in the courtyard outside, and to the putti nearby, with their instruments (fourth image).

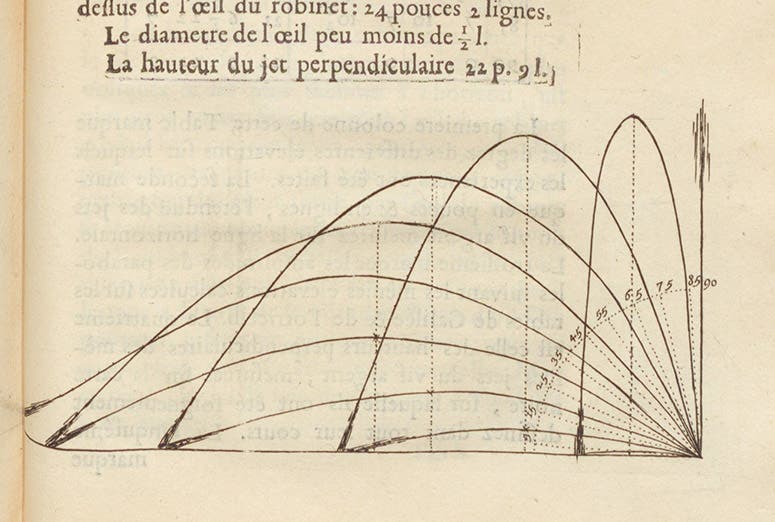

The other Blondel work in our Library is L'art de jetter des bombes, which takes a similarly mathematical approach to ballistics. If masons were resistant to mathematical analysis, contemporary gunners were even worse. There was an established mindset in the military that the art of gunnery was a practical art, leaned by experience, and not at all well-served by instruments of any kind. In his book, Blondel discussed all sorts of sighting, measuring and aiming instruments, that would enable a gunner to choose the proper trajectory to cover the necessary distance to drop a mortar on an enemy installation. He even includes a graph that shows how the angle of elevation of the mortar affects the distance, with maximum distance coming at about 40 degrees (sixth image).

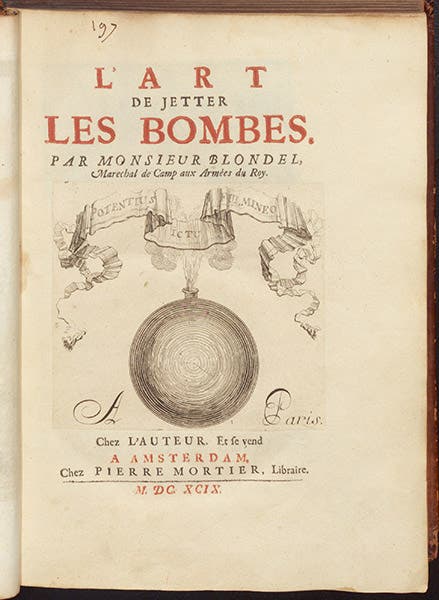

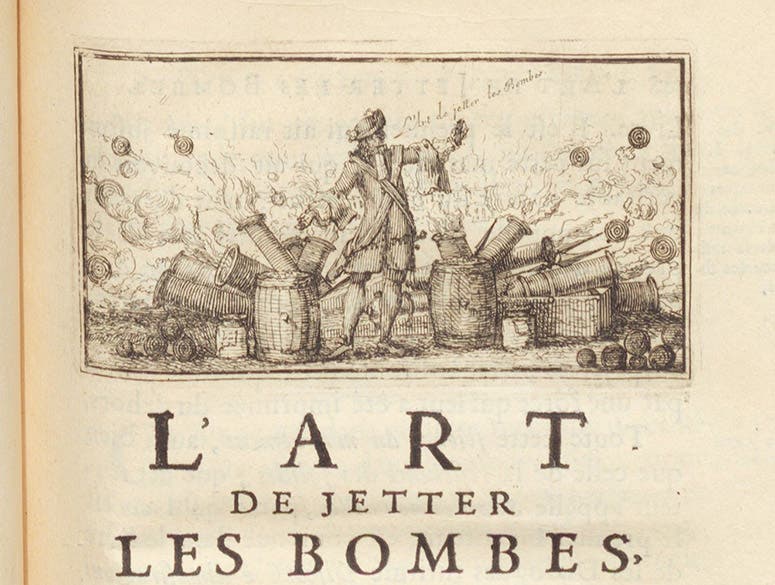

By all accounts, gunners ignored Blondel’s suggestions, as they had ignored the ballistics analysis of Niccolò Tartaglia and Galileo. But L'art de jetter des bombes is still a beautiful book, with the large titlepage vignette of a mortar, with the motto: Potentius ictu fulmineo, “a more powerful thunderbolt” (fifth image). The headpieces are a bit more baroque, and hence probably not by Le Clerc, but they do depict mortars being shot to all points of the compass; we include one of those here (seventh image).

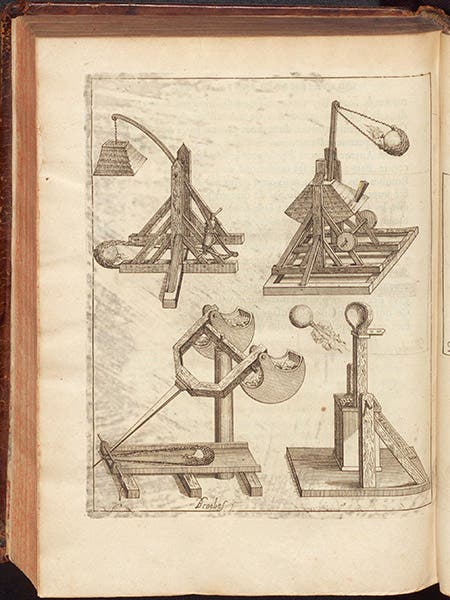

Although bombes could be shot by mortars, they could also be flung by catapults, and Blondel includes several engravings that show a variety of such siege devices. I do not believe that he designed these, but they do make for a busy engraving (eighth image).

L'art de jetter des bombes was first published in 1683. Our copy is a sixth edition, 1699, which means the book was extraordinarily popular. Someone was buying the book, even if the gunners and military engineers were not much interested.

There is no known portrait of Blondel, which is a bit of a surprise, given his social status and the success of his architectural books. He died in 1686.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.