Scientist of the Day - François Jacob

François Jacob, a French molecular biologist, was born June 17, 1920. Jacob's plans to become a physician were interrupted by Hitler and the Second World War; he fled to England in 1940 and joined the Free French Army, served in Africa, and was severely wounded back in France after the invasion at Normandy. After the War, he resumed his medical education and became a physician and surgeon, but because of wounds to his hands, he found he could not function as a surgeon, and so he switched over to medical research, eventually (1954) earning a PhD in biology at the Sorbonne.

Jacob was interested in bacteria and in phages – viruses that take over bacteria and force them to do their genetic bidding. This was an exciting time to be working on bacterial genetics, as a phage is basically just a protein wrapped around a DNA molecule, and if one could figure out where the genetic instructions were – the protein or the DNA – it might be possible to understand how the gene is built, and how it works. Jacob was too late to the game to play any role in deciphering the structure of the gene, although he was present at all the colloquia in 1952 and 1953 that were also attended by James Watson and Francis Crick, who determined that DNA is the genetic material and has the structure of a double helix. Watson and Crick, in their initial paper of 1953, suggested how the gene might replicate – the DNA double helix simply unwinds and separates, and then each half acts as a mirror template to form a new molecule just like the original – but they did not have a clue as to how the instructions in a length of DNA are converted into a protein.

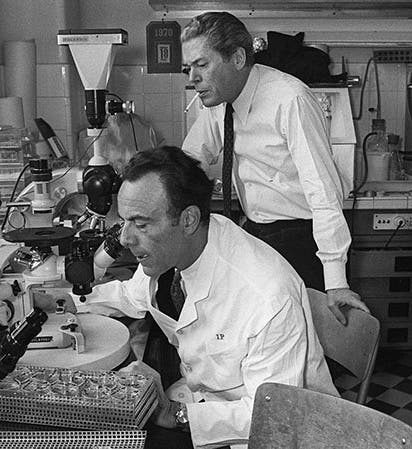

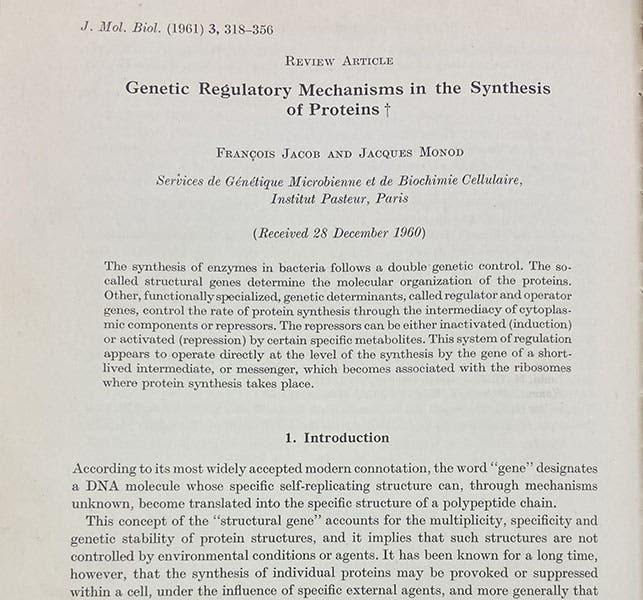

This is where Jacob came in, teaming up with another great biologist at the Institut Pasteur in Paris, Jacques Monod. They knew that bacteria normally produce an enzyme (a protein) to digest glucose, but if they are in the presence of lactose, the bacteria will start making lactase, a lactose-digesting enzyme. How does it know when and how to activate the gene that makes lactase? As they pursued this question in the late 1950s, they gradually unraveled much of the nuclear machinery that allows the gene to express itself. They realized that the genetic code in the DNA strand is copied onto a molecule of RNA by a process known as transcription, and that this RNA molecule – which they called messenger RNA, or mRNA – carries the instructions for building the protein into the cell protoplasm. They also determined that there are molecules – repressors – that can prevent transcription of a gene, and others that can turn the gene on, and they figured out how repression actually works. They announced much of this in a milestone paper, “Genetic regulatory mechanism in the synthesis of proteins," which was published in the Journal of Molecular Biology, in volume 3, indicating how new this discipline was. For their discoveries, Jacob (with Monod and André Lwoff) received the Nobel Prize in Physiology/Medicine in 1965.

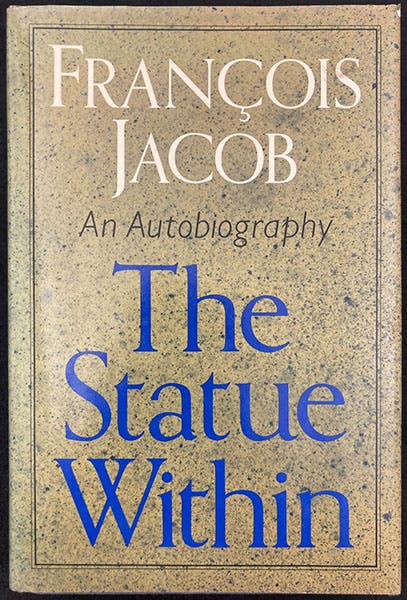

Jacob later wrote an autobiography, The Statue Within (1988), that is well worth reading, since Jacob was an eloquent and heartfelt writer, and he certainly lived through some exciting times. His discussion of the rapid developments that occurred between 1952 and 1960 is especially enthralling. I liked one section where he recalled a meeting of 1959, which Watson attended, and he wrote that Watson, “courteous as ever ,” spent most of the sessions ostentatiously reading a newspaper. When it came time for Watson to read his paper, all of the participants pulled out newspapers of their own. I would love to have witnessed that.

Dust jacket, The Statue Within, by François Jacob, tr. by Franklin Philip (Basic Books, 1988) (author’s copy)

But I found it especially interesting that, after taking us in detail through the war years and the phage decade of the 1950s, Jacob finally got to the writing of his and Monod’s famous paper, which they sent off to the Journal of Molecular Biology on Christmas Eve in 1960, and there the book ends, without even a hint of the Nobel Prize to come. It was as if Jacob were admitting that his creative biological life was over at that moment, even though he had another 53 years to live.

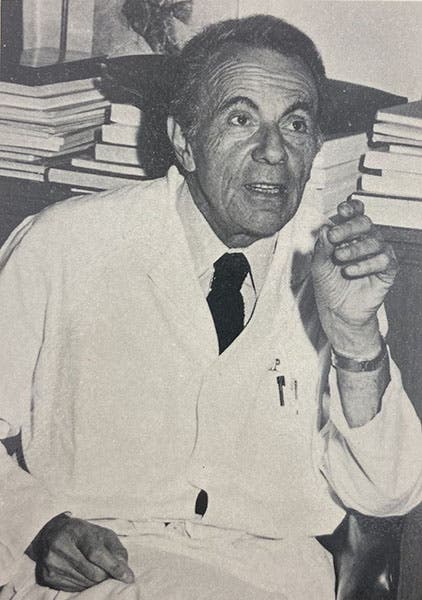

François Jacob as the elder statesman of molecular biology, photograph, inside dust jacket, The Statue Within (Basic Books, 1988) (author’s copy)

Jacob’s book, The Statue Within, was part of a series that deserves a kudo of its own. Alfred P. Sloan may not have been a hero, but his Foundation has given greatly to the history of science, especially by sponsoring a series of autobiographies of scientists, of which Jacob’s was the 11th. Other notable books in the series were Disturbing the Universe, by Freeman Dyson, The Youngest Science, by Lewis Thomas, and Alvarez: Adventures of a Physicist, by Luis W. Alvarez, and books by Peter Medawar, Salvador Luria, and Francis Crick. I own ten of these autobiographies, which are excellent without exception, and I am grateful to the Sloan Foundation for underwriting the series.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.