Scientist of the Day - Frank Drake

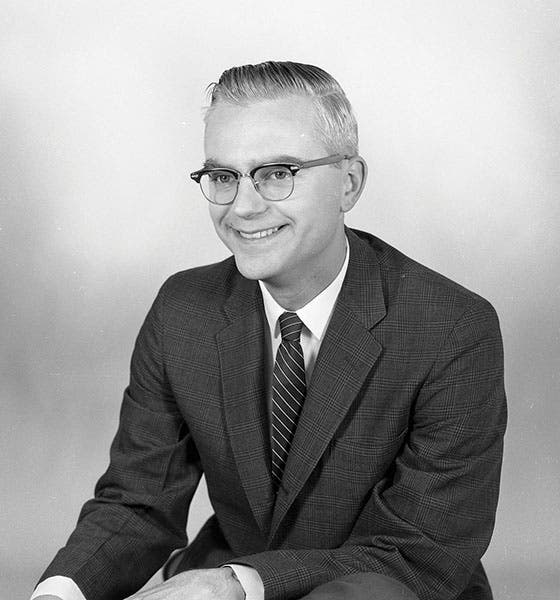

Frank Drake, an American radio astronomer and astrobiologist, was born May 28, 1930, in Chicago. He studied astronomy at Cornell and did his graduate work at Harvard. In 1958, he began work at the National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO) at Green Bank, West Virginia. The observatory was directed by Otto Sturve, one of a long line of Baltic/Russian and now American astronomers (we have written posts on Friedrich G.W. von Struve and Otto Wilhelm von Struve). Otto Struve had an interest in searching for extraterrestrial life, as did Drake, so the two hit it off well.

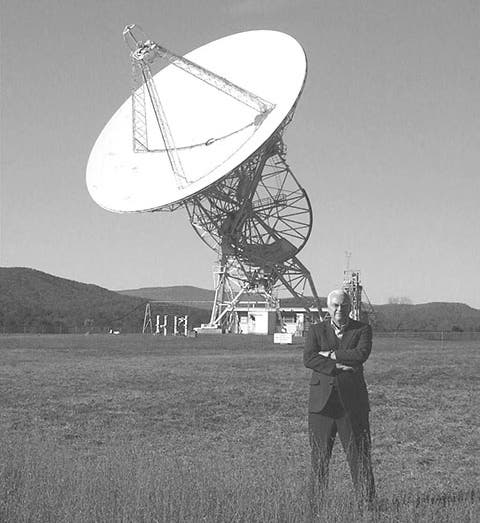

Green Bank began building an 85-foot radio telescope in 1958, and Drake was asked if he would like to undertake a search for signals from space with the instrument (first image). Searching for ET was a taboo in astronomical circles at the time, what with all the UFO furor that had seized public attention in the 1950s, so Project Ozma, as the search was to be called, was a clandestine operation, but Struve gave his enthusiastic approval. Drake was in charge. He and his small team decided to listen at wavelengths of 21 cm, which was the wavelength at which hydrogen emits radio waves, and the hydroxyl emission line is not far away, and it was conjectured that anyone sending signals out into space for communication purposes would use this region of the electromagnetic spectrum clustered around H and OH. Since H and OH make water, that region was called the "watering hole," and Drake and Project Ozma spent four months listening to deep-space static. They chose the stars Tau Ceti and Epsilon Eridani as their targets, since both were Sun-like stars that might possibly have planets, and both were close (10 light-years away), and they were above the horizon at two different times. Drake picked up one very intense and unexpected signal, but later determined that it came from a high-flying aircraft on a clandestine mission. No signals were detected from space. Project Ozma terminated at the end of the summer of 1960. It was the first dedicated search for extraterrestrial intelligent life.

Although his initial inclination was to keep Project Ozma quiet, that changed when Philip Morrison and Giuseppe Cocconi published a paper in Nature in 1959, suggesting that if one wanted to search for extraterrestrial radio signals, the 21-cm line would be a good wavelength to start with. Since Drake and his staff had already figured this out, they didn't want to be scooped, and they went public with the Project. And besides, Morrison and Cocconi had now made the subject respectable – their article was in Nature, the most prestigious science journal in the world.

In 1961, Drake was approached by a member of the Space Science Board of the National Academy of Sciences and asked if he would like to organize a conference devoted to the subject of the search for extraterrestrial intelligent life. Struve was happy to have Green Bank sponsor the meeting, and Drake set about inviting everyone he could think of who might have an interest in such a topic. He came up with 10 names, which included Morrison and Cocconi (Morrison accepted, Cocconi declined). Another person invited was Melvin Calvin, an American chemist who had in the previous decade unraveled the pathway of carbon in the process of photosynthesis. One late invitee was a graduate student at Cornell, Carl Sagan, who had written to Drake after Project Ozma and expressed his interest.

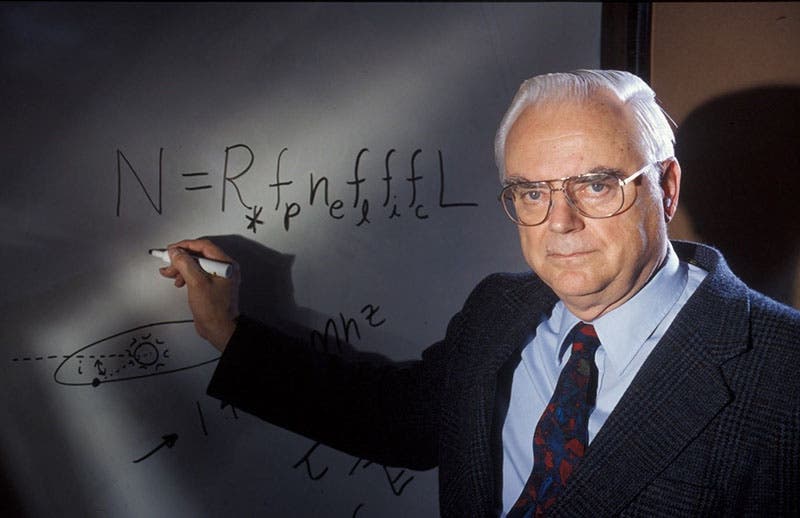

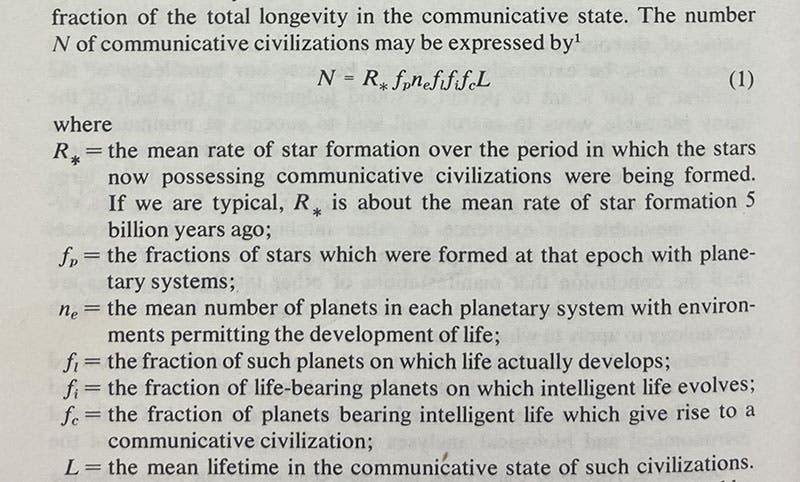

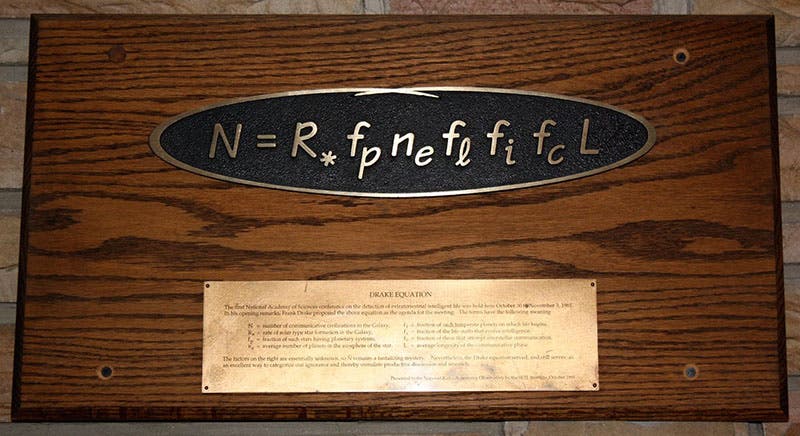

Drake was responsible for the program, and to organize discussion, he came up with an equation for calculating the number of communicating civilizations in our Galaxy. The equation had 7 factors, each of which Drake thought might be a suitable topic for a morning's or afternoon’s discussion. When the participants convened in West Virginia on Nov. 1, 1961, Drake wrote the equation was on a blackboard in the meeting room and they were off and running for three days. The equation has become, sixty years later, some say, the second most famous equation in the world. We show you an older Frank Drake, recreating the blackboard equation (third image), and the first appearance of the equation in print in 1965, where you can, I hope, see the 7 factors and their explanation (fourth image). The factors are things like the rate of star formation, the percentage of stars that might have planets, the percentage of planets that might be habitable, the percentage of planets with life that develop intelligent life, etc. – all of which have to be estimated, since very few (such as the rate of star formation) were known with any certainty.

For me, the most interesting factor has always been the last one, “L” – the lifetime of communicating civilizations. In 1961, when it seemed likely that our civilization would destroy itself in the near future, this lifetime seemed to be about 60 years (the time since we discovered radio), which would make the probability of other intelligent life nearly zero. But if civilizations could last for a thousand times longer, then the number of communicating civilizations would be 1000 times greater. So the longer we go without killing ourselves off, the more likely it is that we have intelligent neighbors in the Galaxy. Since Drake wrote the equation the first time, the lifetime of our communicating civilization has doubled, so the probability of extra-terrestrial life has doubled as well. Can we increase that by a factor of ten? The next millennium will tell. There is a brass plaque in the conference room at Greek Bank, commemorating the site where the Drake equation was first written on a blackboard (fifth image).

Drake made many more contributions to SETI, the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence, as the endeavor came to be called. He and Carl Sagan designed the plaques that were placed on the spacecraft Pioneer 10 and 11, messages for extraterrestrials, to be read in person, and collaborated as well on the Voyager record, sent with Voyager 1 and 2 (which you can see at our post on Sagan).

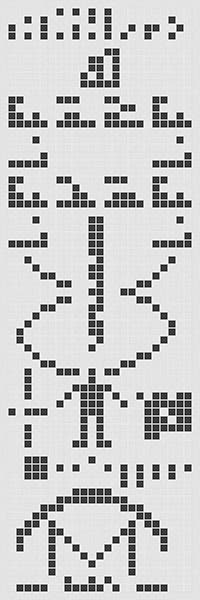

The “Arecibo message,” sent Nov. 16, 1974, from Arecibo Observatory, Puerto Rico, in the direction of the globular cluster, M13, in Hercules. Encoded data include the numbers 1-10, the formulas for DNA bases, a human figure, and an image of the Arecibo radio telescope at the bottom (Wikimedia commons)

But here we show you the first message deliberately sent out from Earth to anyone who might be listening, which Drake compiled (seventh image). It was broadcast from the Arecibo Radio Telescope in Puerto Rico on Nov. 16, 1974, and beamed in the direction of the globular cluster M13 in Hercules, where there were tens of thousands of stars in the path of the radio beam. It was a string of 1679 binary digits (1 or 0), which, when arrayed in a 23 by 73 grid, formed a picture of sorts, showing the numbers 1 to 10, DNA, the structure of the DNA bases, a human figure, and an outline of the Arecibo radio telescope. 1679 is a “semi-prime,” meaning it has only two factors, 23 and 73, both primes themselves. So there is no other way to arrange the signal than the correct one. Drake was not only the first to organize a listening session for extraterrestrials, with Project Ozma, he was the first to try to speak to them, with the Arecibo message.

There are many more interesting facets to Drake’s life – he raised orchids, made jewelry, and served for 10 years as a volunteer on a county suicide hotline – but this piece is already too long. I can recommend a book that Drake wrote with Dava Sobel, Is Anyone Out There: The Scientific Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (1992). It is full of good stories and insights, and is very well-written (the influence of Sobel is suspected). It also includes quite a few photos that are not easily found elsewhere.

Drake died less than 2 years ago, on Sep. 2, 2022, at age 92. His daughter, Nadia Drake, is a well-respected science journalist. She will be coming to our Library on Feb. 26, 2025, to moderate a panel in conjunction with our upcoming exhibition, Life Beyond Earth? Aliens * Exoplanets * UFOs, which will open on Oct. 25, 2024. The exhibition will include a panel on Frank Drake.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.