Scientist of the Day - Friedrich G.W. von Struve

Friedrich Georg Wilhelm von Struve, a German/Danish/Russian astronomer, was born Apr. 15, 1793. Struve became director of the Dorpat Observatory in Estonia (Dorpat is now known as Tartu) in 1820, where he mostly studied binary stars. In 1839, he founded and became director of the Pulkovo Observatory outside Saint Petersburg. For Pulkovo, he commissioned a 15-inch refractor from the optical firm of Merz and Mahler in Munich (first image). This was the largest refractor in the world for some time, although it was matched in 1847 when Harvard College Observatory acquired its twin from Merz and Mahler (see our post on William Cranch Bond for a view of the Harvard "Great Refractor”). We have also written a post on Georg Merz, one of the founders of the Merz and Mahler firm.

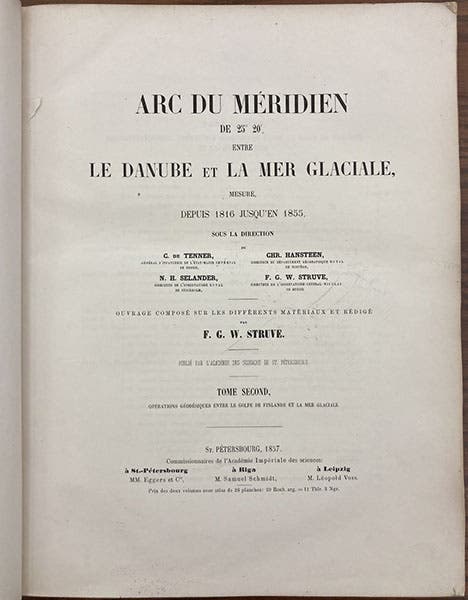

While still at Dorpat, Struve was asked by Tsar Alexander I to supervise a project to measure the length of a long meridian arc, thus allowing one to determine with greater accuracy the size and shape of the earth. We have several times in these notices referred to a similar French project of the 18th century, which attempted to measure the length of a degree of a meridian in Ecuador and in Lapland. But Struve’s geodetic project dwarfed the earlier efforts. Between 1816 and 1855, he and his coworkers managed to measure a meridian that extended from the Black Sea all the way up to the Arctic Ocean, extending over 1760 miles and some 25 degrees of arc. Meridians were almost always measured by triangulation, where one carefully measured with surveyors’ chains a side of a triangle for a base line, and then slowly built up a chain of triangles, extending all the way up the meridian, with the sides of each triangle determined with reference to the first one. The Struve Geodetic Arc, as it was called, was worked out by establishing 258 triangles, using some 265 station points, which was the name given to the fixed points that anchored the chain of triangles. Beginning in 1857, Struve published the first of three volumes on the meridian project, called Arc du méridien de 250° 20’ entre le Danube et la mer Glaciale (1857-60). We have this set in our history of science collection, with the third volume, the atlas, bound into the back of the second volume (third and fourth images).

In 2005, UNESCO made the Struve Geodetic Arc a World Heritage Site, the first time, I do believe, that such a stretched-out cultural artifact was given World Heritage status. Thirty-four of the original station points still survive, and each one, whether a cairn, an obelisk, or a lead disk set into a rock, is now a part of the site. You can view some of these markers on the World Heritage page for the Struve Arc. It was granted a citation because, in the words of the commission, the Struve Arc “is an extraordinary example of scientific collaboration among scientists from different countries, and of collaboration between monarchs for a scientific cause.” We include a modern map of the complete arc below (fifth image)

Struve, the Dorpat Observatory, and the Struve Geodetic Arc were all featured on a postage sheet of 2011, issued by the postal service of Estonia. You can also see there some of the surveying instruments used on the survey (sixth image)

F.G.W. von Struve was succeeded at Pulkovo by his son, Otto Wilhelm von Struve, who replaced the 15-inch refractor with a much larger 30-inch Clark refractor from the United States, in 1885. No one seems to know what happened to the 15-inch refractor put in place by his father (its twin is still proudly displayed at Harvard).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![Andromeda and Perseus, constellations figured by James Thornhill, with star positions determined by John Flamsteed, in Atlas coelestis, plate [15], 1729 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/1b30cfec-5be6-4297-a7fb-97255ba992e5/thornhill1.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)