Scientist of the Day - George F.L. Marshall

George Frederick Leycester Marshall, a career British officer in the Royal Army in India, was born Mar. 27, 1843, in Shropshire. His brother, Charles Henry, also an officer in the Indian Army, preceded him by two years. Both were avid collectors of tropical butterflies and birds. Of the birds, they were especially interested in barbets – brightly colored forest birds with large heads, plump bodies, and bristly beaks, which eat mostly fruit. They are found in Southeast Asia, Africa, and Neotropical America.

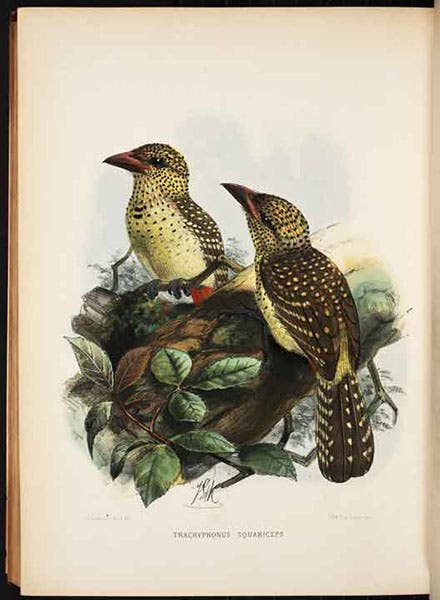

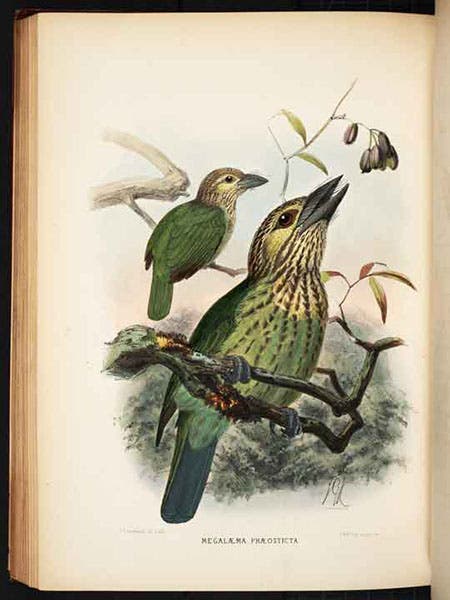

In 1870, when neither brother was yet 30 years old, they self-published what must have been a very expensive volume on the Capitonidae, or Scansorial Barbets (the term Capitonidae is now used only for the New World barbets, but in the 19th century, it also included those of Southeast Asia and Africa). The Marshall brothers attempted to discuss and illustrate every species of barbet. The smartest thing they did was to hire Johannes Gerard (or John Gerrard) Keulemans to draw the lithographs for their volume. Keulemans was a Dutch illustrator, the same age as George, who moved to London in 1868 and was immediately tapped by the Marshalls to draw barbets. He contributed 73 large (quarto-sized) hand-colored lithographs for the Marshall book, and they are all absolutely stunning. Keulemans went on to become one of the most sought-after bird illustrators in England until his death in 1912. He should get most of the credit for the success of the Marshall's book. But it is George's birthday, not Keulemans'.

The barbets shown here are four that struck me, as I leafed through the book, as superb in color and composition. The Marshalls gave them all Linnaean names, but it has been hard to correlate those with modern names, so I gave that up. But the Marshalls did provide short descriptions of each specimen. The Lesser Pearl-Spotted barbet (fifth and sixth images below), lives in East Africa, and they studied and depicted a specimen that had been collected by a Mr. T.C. Eyton, who graciously lent it to them for their book. The last bird shown, which Marshall calls the Cochin China green barbet, came, as the name tells us, from Vietnam, and only a single specimen is known, that in the Leiden Museum, which was also lent to the Marshalls and Keulemans as the book was compiled. Collectors were very generous with their specimens in those days, as Charles Darwin found out when he borrowed barnacles from all over for his book.

One odd feature of Scansorial Barbets, which makes it somewhat difficult to use, is that the plates are numbered in the Table of Contents, but they are not numbered in the text, or on the plates themselves. That certainly makes it hard to look up a particular bird.

I tried to find out more about George Marshall's life, with little success. There are no portraits of either George or Charles, and no images of anything in their lives except the barbets. I am not sure why we even know the birth and death date for George (he died Mar. 7, 1934, so he lived to be almost 91 years old). One would think the introduction to the barbet book would have some biographical information, but it does not. So when we think of George Marshall, we are forced to think mostly of barbets. And that is not such a bad thing. I for one would be happy to have a legacy like that.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.