Scientist of the Day - George Rowley

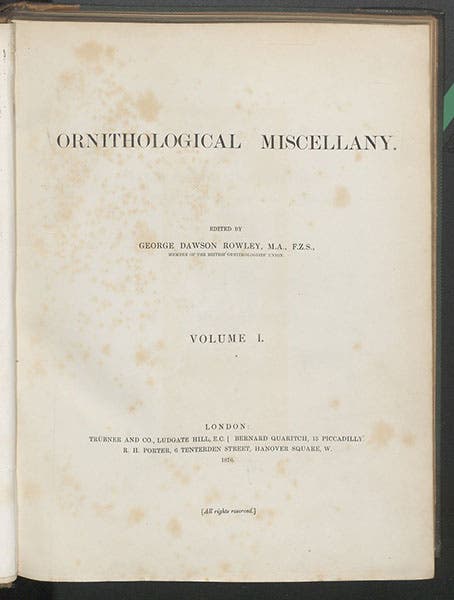

George Dawson Rowley, an English student of birds, was born May 3, 1822. Not much is known about Rowley, except that he studied at Trinity College, Cambridge, and settled down in Brighton, apparently living on family money. He was passionate about birds, and he collected them, the exotic ones by purchase. He contributed some articles on birds to Ibis, the bird journal founded in 1859, but in 1875, he began issuing his own periodical, Ornithological Miscellany. He wrote many of the articles himself and commissioned or was receptive to articles by others. Four issues were published each year, and they are lovely things, being of quarto size, and illustrated with colored lithographs by John Gerard Keulemans, a prodigiously prolific illustrator of birds about whom we have already written a post (but without mentioning Rowley). The Ornithological Miscellany continued for three years, until Rowley fell ill and died within a year, 57 years old, passing away on the very same day as his aged father, which must not happen very often.

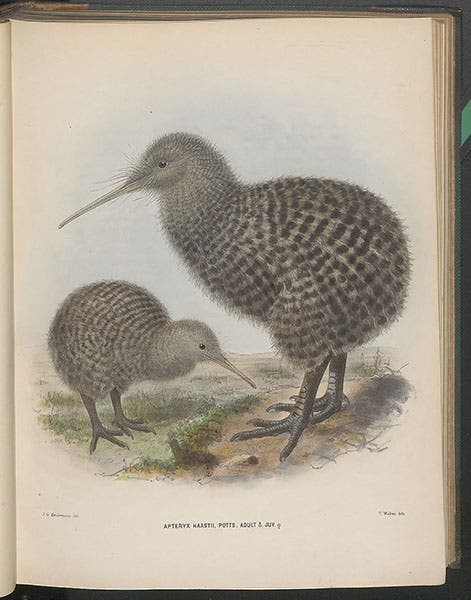

All of our images today come from volume one of the Miscellany, containing the first four issues, which we had scanned for the occasion (volumes 2 and 3 are waiting their turn). It is fun to browse through the pages, not only because the lithographs are beautiful, but because Rowley liked to collect odd facts about birds as well as birds themselves, and he enjoyed sharing these with the reader. And sometimes he just liked to show off his collection. For example, the first article in volume 1 is on the kiwi of New Zealand, of which two species were known, until a certain T.H. Pott described a third kind, Apteryx haasti, in 1871. Rowley went to some effort to obtain four specimens of the Haast kiwi for his collection, two adults and two young, and these were the ones portrayed by Keulemans in his painting (second image). Rowley had this to say about the kiwi: "The Apteryx conveys to one's mind something peculiarly mysterious; and though not yet extinct, it seems as if it ought to be. It has lingered on in a world where its place is gone."

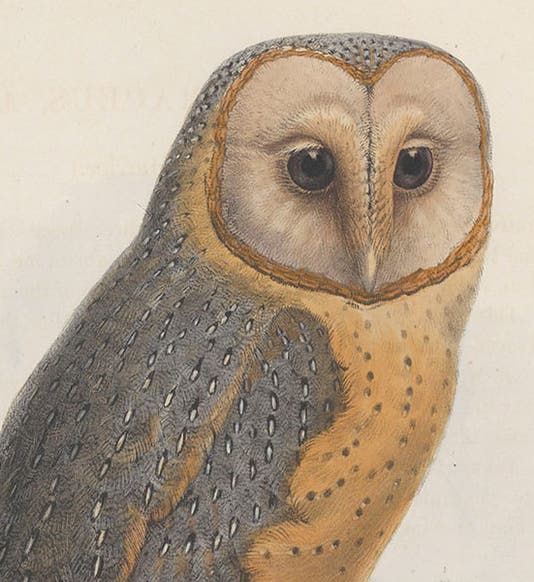

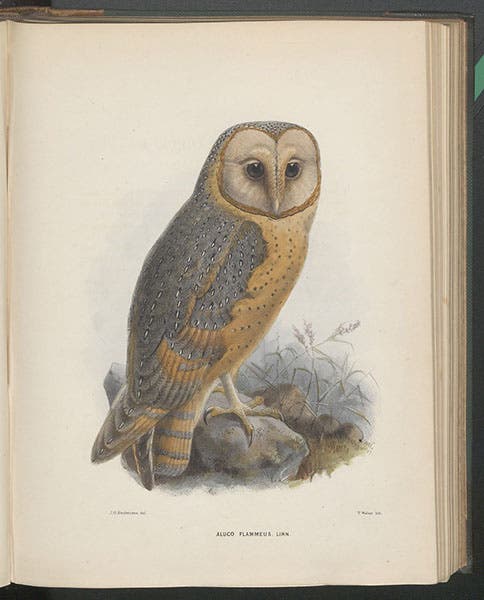

Another article is about the birds of England, which really ought to be titled, "A few select birds of England,” since it only considers a half-dozen species. But it does contain my favorite Keulemans illustration, of a barn owl. We show a detail as our first image, and also the full plate here (third image, just above). I think it is the coloring that makes this bird stand out from the others. Or perhaps it is the lack of a background, unusual for a Keulemans print.

I also enjoyed reading Rowley’s article about the desert larks of the middle East, which Rowley calls "isabelline birds," so that he can then proceed to tell the story of this name. Isabelline is a color – brownish yellow – and Rowley informs us that the term had its origins in an event in the life of Isabella, daughter of Philip II of Spain, and herself the Infanta of Spain. Isabella’s husband in 1601 undertook a siege of the town of Ostend, and Isabella vowed not to change her linen undergarment until the siege was successful. However, the town did not fall until 1604, by which time her undergarments were very much the color of the desert lark. The origin of the color isabelline has since been shown to be unrelated to Infanta Isabella, since its first use predates the siege of Ostend, but it is a delightful story nevertheless, which Rowley tells with great gusto. Indeed, I suspect it is why he included the desert larks in his book in the first place. Keulemans did not need much of a palette to paint them (fourth image, above).

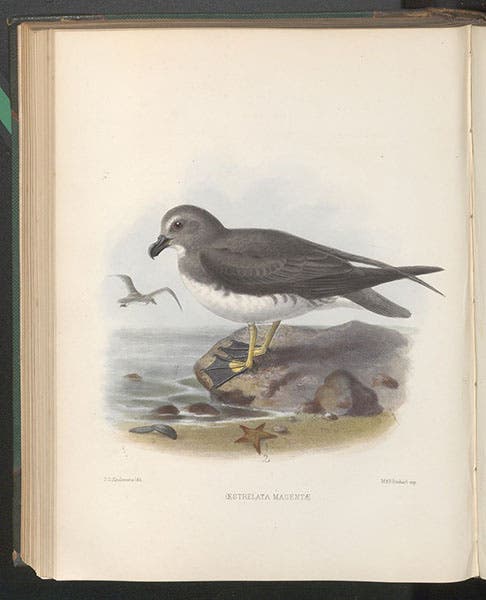

The other two images here were chosen because the detail of the yellow-cheeked warbler has Keulemans’ characteristic monogram beneath, "JGK" (fifth image, just above). The other lithograph, depicting the magenta plover, warns us that names can be deceptive. The magenta plover has not a tinge of magenta on it. Rather, its name comes from the Magenta, the ship that plucked this plover from the middle of the Pacific Ocean (sixth image, just below).

Finally, we would like to point out that the Keulemans illustrations here are chromolithographs, printed in color with multiple stones. This is notable because his other lithographs of this period – and discussed in our post on Keulemans – are hand-colored. This may have been Keulemans’ first experiments with printing in color.

Some day we will open and scan volumes two and three of the Ornithological Miscellany, and see if they have anything new to tell us about Rowley, or the birds of the world. It would be nice if volume 3 contained a portrait, but I am not optimistic. If there were, it would surely have showed up online. But there does not seem to be a portrait of Rowley out there anywhere.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.