Scientist of the Day - Giovanni Battista Benedetti

Giovanni Battista Benedetti, an Italian Renaissance mathematician and philosopher, was born Aug. 14, 1530, in Venice. He came from a well-placed family and was apparently never wanting for money. He was mostly self-taught. He spent some time as a student of Nicolo Tartaglia, but neither believed that the brief relationship was meaningful. Benedetti was never a professor, and served mainly as a court philosopher, first at Parma, then at Turin, where he died in 1590.

Benedetti is often grouped with Federico Commandino and Guidobaldo del Monte as the triumvirate who began the restoration of Archimedean mechanics in 16h-centuy Italy, as an alternative to Aristotelian physics, and set the table for Galileo and the birth of modern physics. There is little doubt about the significance of Commandino and del Monte in the Archimedean revival, but the importance of Benedetti is less certain. The claim is that, in three short treatises published in 1553-1554, Benedetti denied the Aristotelian assertion that heavy bodies fall faster than lighter ones, and maintained that the laws of free fall depend on density, so that two objects of different weights but made of the same material would fall at the same rate. In the last treatise, he argued that in a vacuum, in the absence of a resisting medium, any two objects would fall at the same rate. This would all seem to foreshadow the conclusions of Galileo 40 years later.

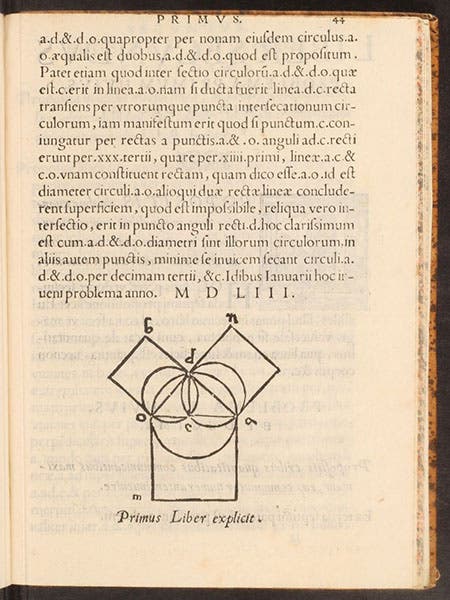

We have the first of Benedetti's three treatises, the Resolutio of 1553, and it is a beautiful little thing, with strong woodcut diagrams (the book is mostly about Euclid, and only in the letter of dedication to Gabriel de Guzman (third image) does Benedetti take on Aristotle's doctrine of free fall). But the problem is, as far as we can tell, Galileo never read this, or anything by Benedetti, and he never mentioned Benedetti in any of his books or correspondence. So to call Benedetti "the most important immediate forerunner of Galileo," as one eminent scholar did, seems extreme, however much we admire Benedetti's willingness to attack the Aristotelians.

But Benedetti has other claims to fame. Around 1562, he wrote several letters in which he argued that musical consonance is not the product of some metaphysical concord of numerical ratios, but was the result of the fact that vibrating strings produce waves, and sometimes the waves line up and sound good, and sometimes they don't. He was anticipating the work of Isaac Beeckman and Marin Mersenne in the 17th century, and since the letters were published in 1585, in his Diversarum speculationum, his surmise might have had some effect on musical experimentation in the 17th century. We do not have the Speculationum, a collection of miscellaneous letters and papers published late in his lifetime that is considered Benedetti’s most influential work. We would like to acquire it.

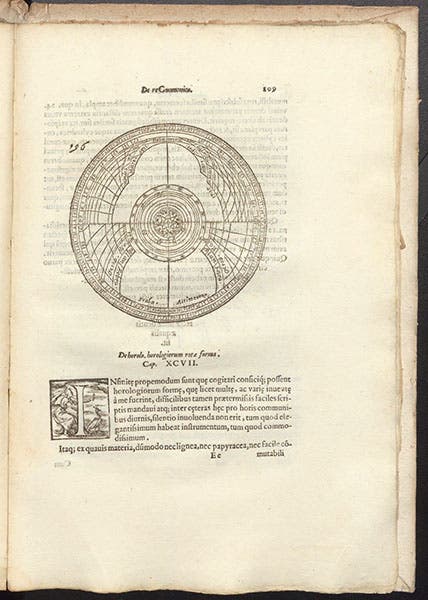

We do have Benedetti’s De gnomonum (1573), a folio-sized treatise on sundials, the first of its kind, and one other work. We also have a number of Renaissance and 17th- century portrait books, with engravings of all manner of Italian philosophers and mathematicians. I was surprised to discover that Benedetti does not appear in any of them. Indeed, there is no portrait of Benedetti anywhere, as far as I know. I wonder why, or why not.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.