Scientist of the Day - Giovanni Battista Riccioli

Giovanni Battista Riccioli, an Italian astronomer, was born Apr. 17, 1598. When we first featured Riccioli two years ago, we discussed the system of lunar nomenclature that he introduced in his Almagestum novum of 1651, which became the basis for our modern practice of naming features on the Moon. We promised at that time to delve one day into the rich frontispiece that opens the New Almagest. Today is that day.

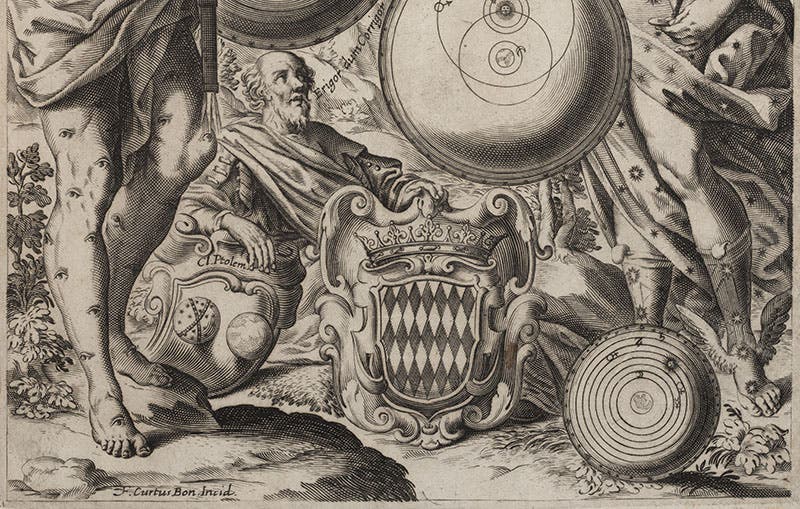

The frontispiece (second image) is one of the masterpieces of Baroque book illustration, drawn by Francesco Curti under the guidance of Riccioli. It depicts two standing figures who are performing a weighing of world systems. The figure on the right is Astraea/Virgo, with her zodiacal belt; she is holding the balance. The left-hand figure is Argus, the hundred-eyed shepherd giant who was supposed to protect Io from the advances of Zeus. He failed at that job, but as an emblem for the astronomical observer, he is perfect, for he can look everywhere. One of his eyes, on his knee, even observes the Sun through a telescope (third image).

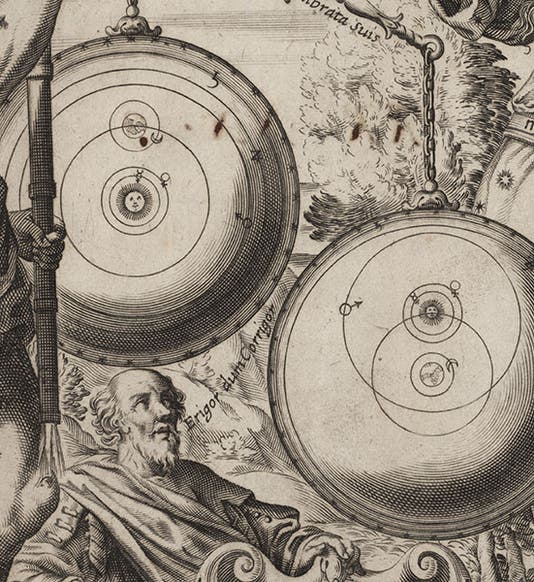

The two world systems hanging from the balance are easy to identify (first image). The one on the left is the Copernican system, with the Sun at the center and the Earth as a planet. The cosmology on the right is a modified Tychonic system, with the Earth at the center, the inner planets orbiting the Sun, and the outer planets orbiting the Earth. The results of the weighing is apparent; the modified Tychonic sytem is more substantial and to be preferred.

And what tips the balance in favor of the Earth-centered cosmology? Scripture, that's what. We see several snippets from verses of the Psalms at the top (fourth image); the phrase uttered by Astraea is the crucial one: "...and it will not be removed forever," the end of a verse that begins: "He has established the Earth on its foundations... . Another verse at the top, "Day unto Day brings forth speech, and Night unto Night indicates knowledge" is just perfect for representing the division of the heavenly bodies into those that are Sun-centered, on the left, and those that are Earth-centered on the right. Riccioli even throws in a phrase from Ovid’s Metamorphoses along the balance arm: “ponderibus librata suis – poised by its own weight.”

And what about the old Aristotelean-Ptolemaic system that prevailed for so long before Tycho Brahe and Copernicus? It has been discarded, no longer under consideration, rolling out of sight at bottom right, while Ptolemy himself gazes upward at the cosmological weighing and says: "Erigor dum Corrigor – I am enlightened even while being corrected" (fifth image).

The Riccioli frontispiece is one of the finest emblematic engravings of the entire century – certainly it ranks right up there with the frontispiece of Johannes Kepler's Rudolphine Tables (1627) in terms of the attractiveness of its composition and the cleverness of the visual argument. It accurately and beautifully represents the Jesuit position on cosmology in the aftermath of the condemnation of Galileo.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.