Scientist of the Day - Giovanni Dondi

Giovanni Dondi, an Italian clock maker, died Oct. 19, 1388, at the age of about 58. Dondi was raised in Padua, where his father was also a clockmaker, one of the very first, as mechanical clocks were a 14th-century invention. In 1348, when still in his teens, Giovanni began work on an astronomical clock, a clock that would show not only the time and date, but the positions of the seven objects considered planets at the time: Sun, Moon, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. The best handbook for determining planetary positons in Dondi's time was the Theorica planetarum, which used the epicycle-different devices from the Almagest (138 C.E.) of Ptolemy of Alexandria to predict the positions of the planets, and that is what Dondi used to make his mechanisms.

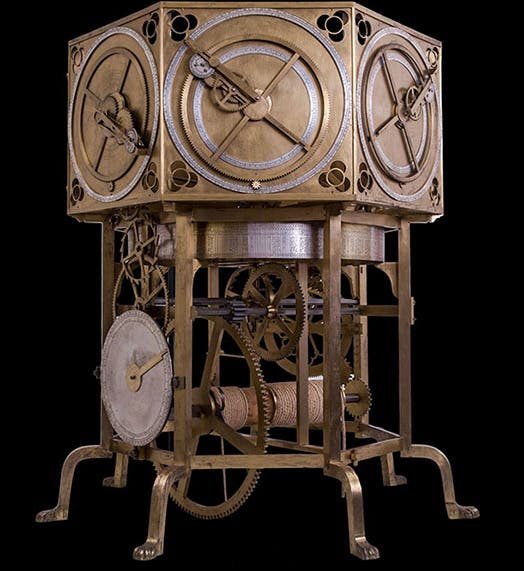

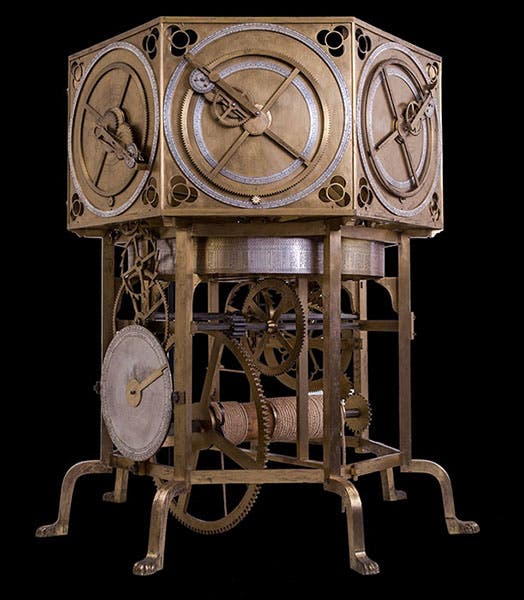

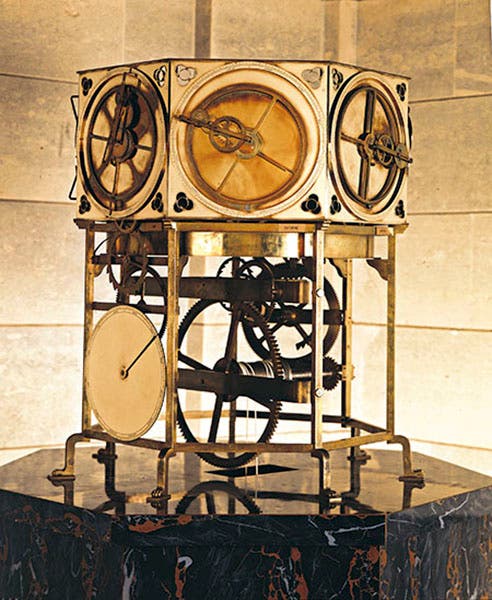

Giovanni finished his clock in 1364, so it took him about 16 years to craft it. He called his handiwork his Astrarium, and it stood about one meter tall. It was octagonal in shape, with 7 faces at the top for each of the planets, and one face left open. The weight-driven clock mechanism was below, as was the face that told the time. All of the dials were driven by the escapement powered by the weight. There were 107 moving parts in all.

Dondi's clock was considered the wonder of his age, since there had never been a mechanism like it. Dondi was given the expanded name, Giovanni Dondi dall'Orologio – Giovanni of the Clock. Indeed, had his Astrarium survived, it would be a wonder of our age. But it did not survive. Clocks eventually quit working and need to be adjusted or repaired, and if no one can get it back in running order, it gets stuck on a shelf and is eventually tossed out by someone cleaning house. Dondi’s Astrarium eventually disappeared.

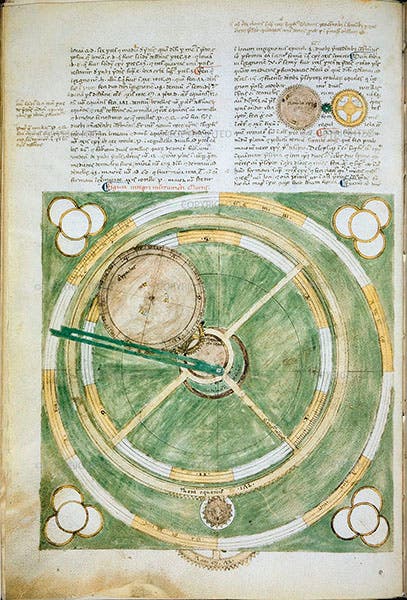

Fortunately, Dondi wrote a treatise about his Astrarium, which described in detail all the parts and illustrated many of them, and told how to put them together. The treatise was faithfully copied once – both the original and the fair copy are in Padua. We include here one of the pages of the Padua original, showing the Venus dial (fourth image). Then other copies of the manuscript were made, which were not quite so faithful – 12 in total, which is a remarkably high number for a technical manuscript. The manuscript is detailed enough to allow for a reconstruction of the original clock, and at least eight of these have been made, although surprisingly, interest in doing so dates from only the 1960s. There is a replica in the National Museum of Science and Technology Leonardo da Vinci in Milan (first image); another in the International Museum of Horology in La Chaux-de-Fonds, Switzerland; one in the Science Museum, London; and one in the National Museum of American History at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C (second image). The best-looking replica is in Milan, and we opened with a view of that one. The most accurate reproduction is considered to be the one in the Paris Observatory (third image). But all of them are beautiful, and mechanically amazing, as you can see from the photographs.

The Padua manuscript has been reproduced with a commentary by the builders of the Paris replica. We have this work in our general collections. We also have a printed edition of the medieval Theorica planetarum that Dondi used for his planetary mechanisms, included in our 1478 edition of Sacrobosco’s Sphaera, if you want to build your own Astrarium and double-check Dondi’s calculations.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.