Scientist of the Day - Giovanni Pico della Mirandola

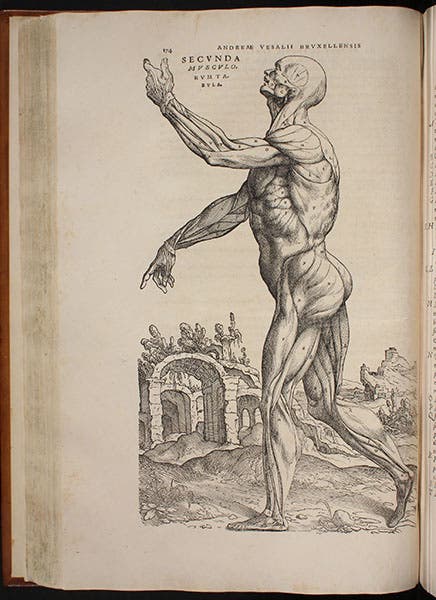

Giovanni Pico della Mirandola, a Renaissance humanist, was born Feb. 24, 1463. In 1486, at the ripe age of 23, Pico published a list of 900 philosophical doctrines, inviting scholars to come from far and wide to Florence to debate any or all of these theses in a public forum in early 1487. Since the list of 900 philosophical theses included doctrines from Zoroastrianism, Platonism, Hermeticism, the Jewish Kabbalah, and many other esoteric disciplines, the Pope declared some of these ideas heretical and forbade a public debate. Pico then published an Apologia and defended his forbidden doctrines, which prompted the Pope to ban all 900 theses and reiterate that no public forum would be forthcoming. So what might have been a most interesting meeting of minds never took place. Pico della Mirandola was about 30 years younger than Marsilio Ficino, the Florentine humanist who had recovered and translated the works of Plato in the 1460s and established the Platonic Academy of Florence under the patronage of Cosimo il vecchio de' Medici. By the 1480s, when Pico came of age, Cosimo had been succeeded by Lorenzo de' Medici, who was equally enlightened and continued to support Ficino, the Academy, and Florentine Platonism. Pico della Mirandola came to Florence and met Lorenzo and Ficino in 1484; both older men took an immediate liking to the impetuous and exuberant youth. Ficino believed that Plato, Aristotle, and Christianity were perfectly compatible, so he was fairly eclectic himself. But he was probably taken aback when Pico extended his eclecticism to include Persian religions, Greek mystery religions, Egyptian hermetic writings, and even Islam. Pico thought that every known religion and philosophy had made a essential contribution to our faith and knowledge, and that once it was all sorted out and put in order, we would have a greater understanding of our world. Pico della Mirandola had planned to give an introductory address before the proposed public debate, and he published it along with the 900 theses late in 1486. The debate may have never taken place, but the printed oration took on a life of its own and has become one of the most famous manifestos of the Renaissance, included in every Renaissance source reader since the mid-19th century. The short treatise is usually titled "Oration on the Dignity of Man,” and it proposes a view of human possibilities that is strikingly new and bold. Pico argues, essentially, that human potential is limitless; that we can ascend to the ranks of angels if we have the knowledge and the will. Here is the heart of the oration; the speaker is the 'Great Artisan', and he is addressing 'Man': "I have set you at the center of the world, so that you may more easily survey that which is in the world. We have made you a creature neither of heaven nor of earth, neither mortal nor immortal, so that you may, as the free and honorable shaper of your own being, fashion yourself in the manner you prefer. You shall be able to descend among the lower forms of being, with the brute beasts; you shall be able to be reborn out of the judgment of your own soul into the higher beings, which are divine." For some reason, when I read this passage, I always think of the second muscle-man woodcut from the De fabrica of Andreas Vesalius. Since we have few other images for this post, I include it just below.

Pico was also good friends with Girolamo Savonarola, the Dominican preacher who would eventually captivate the Florentine populace, and with Angelo Poliziano, the humanist tutor to Lorenzo’s children. Indeed, it is thought that Pico and Poliziano were lovers. After Lorenzo died in 1492 and his weak son Piero (the Unfortunate) came to power, Savonarola gained more and more power in Florence, and as Piero mishandled matters such as the French invasion of Florence, Piero and all the Medicis were exiled from Florence in 1494, and it appears that one of Piero’s last acts may have been to order the deaths of Pico and Poliziano. Both men died in 1494 within months of each other; an exhumation and forensic exam in 2007 revealed that both perished from arsenic poisoning, with Piero as the main suspect. Perhaps Piero resented Pico’s role in bringing Savonarola back to Florence and costing the Medici family their de-facto rule. Pico was only 31 years old when he died.

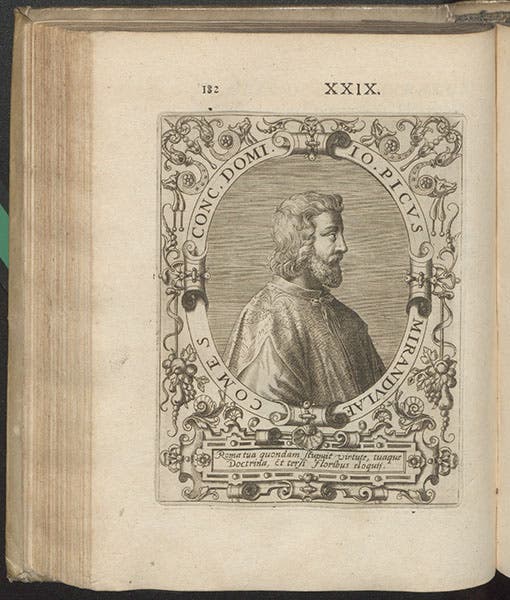

The best known portrait of Pico, by Cristofano dell'Altissimo, is a posthumous one, now in the Ufizzi; we show it as our opening image. We also have a printed portrait in our own collection, in a portrait book that was published in 1597 (third image). Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.