Scientist of the Day - Godfrey Kneller

Godfrey Kneller, an English painter, died Oct. 19, 1723, at age 77. Kneller came to England from Germany in the 1670s, wowed everyone with his portraits, and became principal portrait artist to the courts of Charles II, James II, William and Mary, and George I, active from 1675 until his death. He painted portraits of all of his kingly, queenly, and princely patrons, many times over, and was rewarded with a knighthood and a baronetcy. He is said to have been the only painter raised to a peerage until 1896.

However, we do not care how many kings an artist portrays – if he or she does not paint portraits of scientists or natural philosophers, no space will be granted here. Fortunately, Kneller portrayed several scientists. The first we show you is Christopher Wren, whom you may think of as an architect – and he was one of the truly great ones – but who was better known before the original St. Paul's even burned down as a mathematician of some genius and a Founding Fellow of the Royal Society of London. By the time Kneller painted him in 1711 (second image), the dome of the new St. Paul's had risen and was now inseparably linked to Wren, so Kneller showed the plans for the structure on the table next to his sitter. In my opinion, he should have portrayed Wren standing next to the beautiful wooden model that Wren built of St. Paul’s, which we showed in our post on Wren.

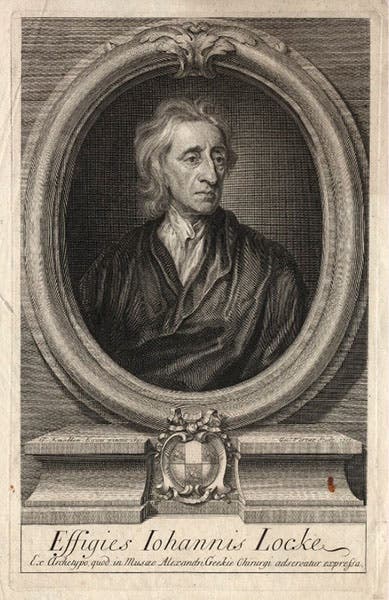

Another eminent philosopher portrayed by Kneller was John Locke. We do not think of Locke as a natural philosopher today, but in his day, with his concern for how the human mind acquires knowledge and understanding, he was considered in the same light as René Descartes, who wrestled with the same problems. Kneller’s original oil portrait of Locke is in the National Portrait Gallery in London. But in this case, we show you one of the many engravings made after the portrait, this one by George Virtue (third image). Nearly every Kneller portrait was immediately engraved for sale, and sometimes, as in this case, the engravings are more appealing than the original, which you may see as the third image in our post on Locke.

And before we get to the pair of portraits for which Kneller is most famous, we show you his ink and wash drawing of William Stukeley, the noted antiquary and student of the stones at Avebury and Stonehenge, and to whom we are indebted for the story of Isaac Newton and the apple tree (fourth image). We wanted to show you this one, because it is such a different style of portrait from the formal oils that usually engaged Kneller. We did not include Kneller’s portrait in our post on Stukeley.

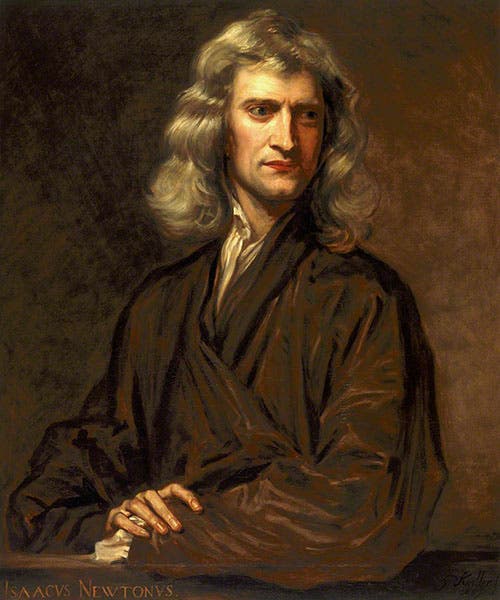

And speaking of Newton, we come now to Kneller’s pair of pièces de résistance, his two portraits of Isaac Newton. The first was executed in 1689, soon after Newton had completed his monumental Principia (1687) and was at the height of his intellectual powers. The original painting is the property of the Duke of Portsmouth, who strictly (perhaps over-strictly) limits reproduction rights. But it has been copied many times, the finest being one made around 1863 from the original, and is now in the Science Museum, London (fifth image).

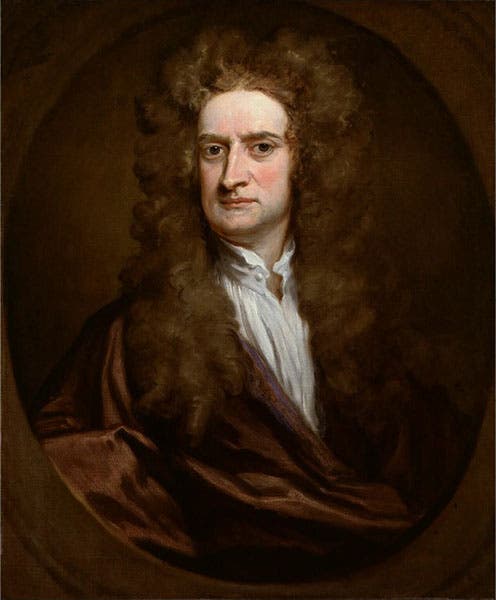

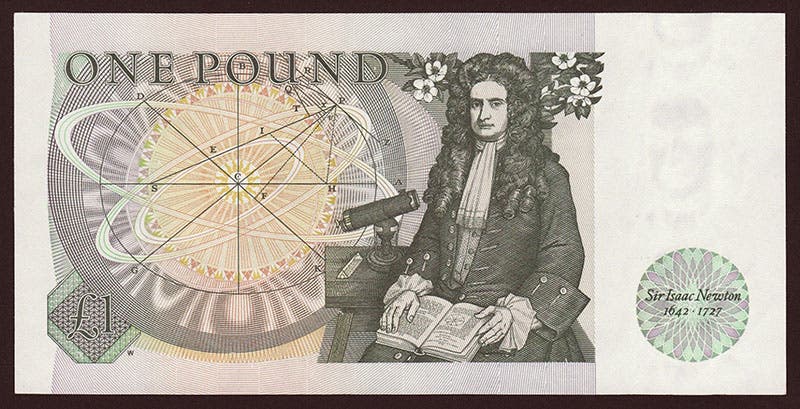

Thirteen years later, just before Newton was knighted and elected to the presidency of the Royal Society, Kneller painted him again. This portrait is available for all to see at the National Portrait Gallery (sixth image). When the British Mint decided to honor its most famous scientific son by putting his portrait on the back of the one-pound note (monarchs, of course, go on the front), it was Kneller’s 1702 portrait that was used as the basis for the engraving (seventh image).

Kneller supposedly declined burial in Westminster Abbey, claiming that too many fools were interred there. Instead, he chose St. Mary’s Churchyard in Twickenham, Middlesex, for his final resting place. The Abbey settled for a marble monument with a bust, which you will find beneath a window in the south choir aisle (eighth image). Kneller is the only portrait painter honored in Westminster Abbey.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.