Scientist of the Day - Grove Karl Gilbert

Grove Karl Gilbert, an American geologist, was born May 6, 1843. In 1869, navigating down the Colorado River, John Wesley Powell, had spotted a mountain range in southeastern Utah, to the west of the river, which he called the Unknown Mountains. Five years later, he was director of the Geological Survey, and he asked Gilbert to journey to the area and survey the mountain range, which now bore the name of the Henry Mountains, after Joseph Henry, the first Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. Powell thought that perhaps the mountains were volcanos – they appeared so from a distance.

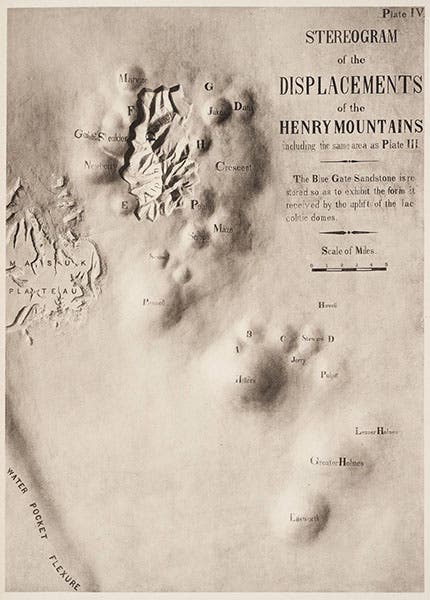

The Henry Mountains were the last mountain range in the U.S. to be named and surveyed. Gilbert discovered, first of all, that these were not volcanoes. Instead, he thought that the mountains had formed when magma welled up underneath the crust but failed to break through, instead forming a number of "blisters" on the surface. Over time, the overlying rock eroded away, revealing the frustrated volcanic core of each dome, which constitutes the present mountain range. Gilbert coined the word "laccolite" for mountains formed in such a manner; this term has been modified into our modern word, laccolith.

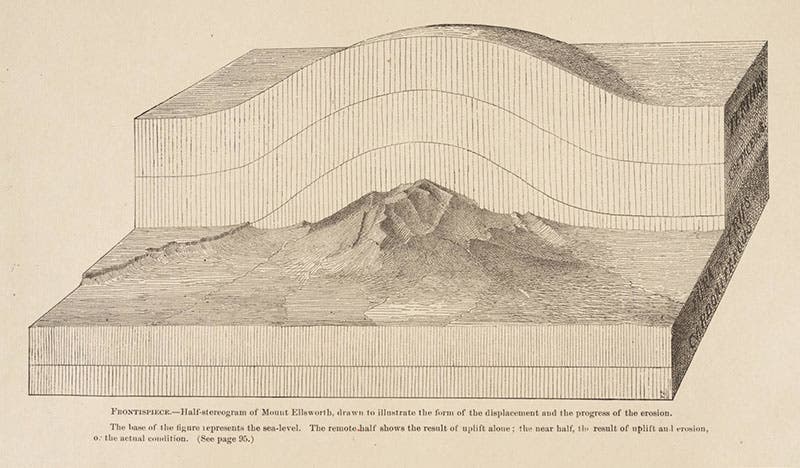

Gilbert published A Report on the Geology of the Henry Mountains in 1877. The book is illustrated with several unusual plates. The frontispiece shows what Gilbert calls a "half-stereogram" of Mt. Ellsworth, the southernmost of the five Henry Mountains (second image). The back part of the diagram - the stereogram part - replicates the appearance of the original up-raised dome of the mountain; the front half shows the present condition, with the surface rock eroded away.

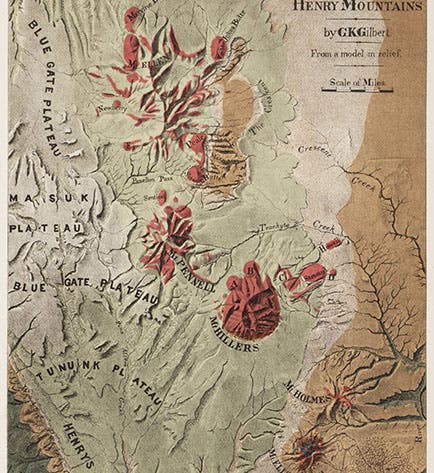

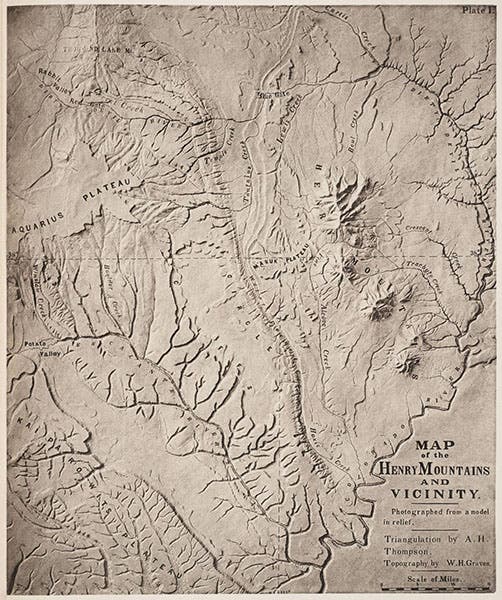

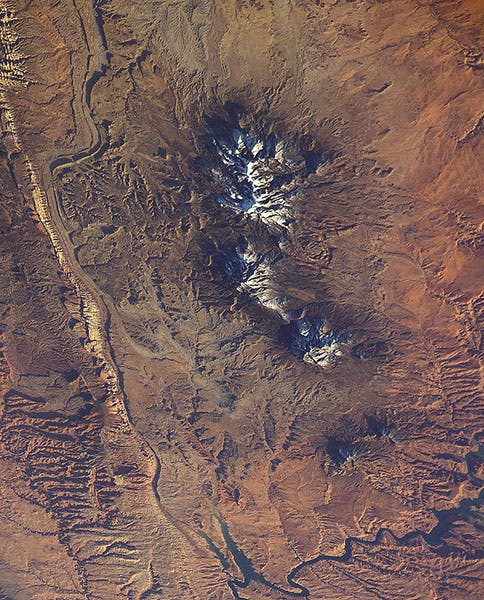

Gilbert also included three maps of the area. The first (third image) showed the larger area, the second a close-up of the Henry Mountains. Interestingly, these are both photographs of relief models that were made after the survey. The third map is a duplicate of the second, except that it is colored (first image). There is a legend and a color index on the left which we do not reproduce here in order to make the map as large as possible. It is interesting to compare the first map (third image) with a LANDSAT photograph of the area (fifth image). We displayed Gilbert’s book in our 2004 exhibition, Science Goes West, and because of the clever way the plates are mounted, we were able to show the frontispiece, the title page, and the colored map, all at the same time.

Gilbert later became involved in the end-of-the-century controversy over the origin of craters, on the Earth and the Moon. He examined Meteor Crater in Arizona and mistakenly concluded that it was not formed by a meteorite impact. But he also argued that lunar craters are impact craters, at a time when most geologists suspected they were volcanic, and here Gilbert turned out to be correct. We may discuss this debate on a future occasion.

The photograph of Gilbert is from a 1900 issue of Popular Science Monthly. Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![Andromeda and Perseus, constellations figured by James Thornhill, with star positions determined by John Flamsteed, in Atlas coelestis, plate [15], 1729 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/1b30cfec-5be6-4297-a7fb-97255ba992e5/thornhill1.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)