Scientist of the Day - Guglielmo Marconi

Guglielmo Marconi, an Italian electrical engineer and inventor, was born Apr. 25, 1874, into a wealthy family in Bologna. His mother was Irish, and he spent several childhood years in England, where he became fluent in English. He was educated by tutors and never formally attended a university.

In his late teens, Marconi learned about the work of Heinrich Hertz, who had demonstrated the existence of electromagnetic waves in 1888. Such waves had been predicted by James Clerk Maxwell in 1873. Hertz's sad death in early 1894 triggered an outpouring of eulogies, one by an Italian physicist who was tutoring the 20-year-old Marconi. Marconi began building his own transmitters and receivers, attempting to use them for wireless communication.

One of Hertz's eulogists was Oliver Lodge in England, who had developed a detector known as a coherer, which consisted of a tube filled with iron filings that changed resistance when in the presence of an electromagnetic wave, thus serving as a detector. Coupled with a spark-gap transmitter, which used an induction coil and a key- switch to zap the air, Lodge could create and detect a radio wave. Marconi built his own transmitter and coherer-detector and began experimenting intensively. By 1895, he could detect waves from his spark-gap transmitter, which greatly impressed his mother, who had supported his work from the beginning.

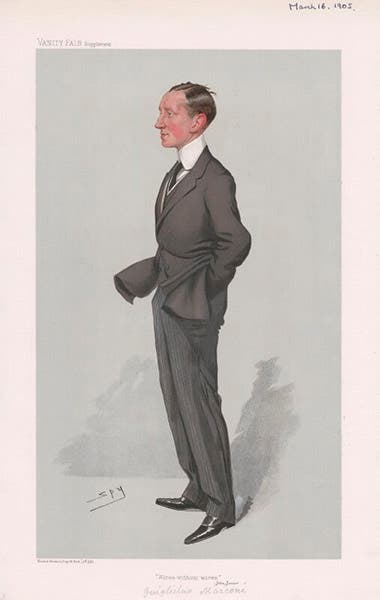

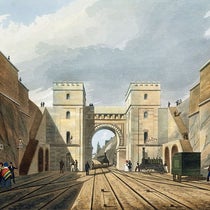

Marconi applied to Italian authorities for support, with no success, so his mother suggested they go to England and seek assistance there. With the help of the Italian ambassador in London, Marconi was introduced to William Preece, the chief electrical engineer of the General Post Office ( GPO), who was quite impressed with the quiet young Italian (Marconi was 21 at the time) and his ingenious ideas. On Dec. 11, 1896, Preece gave a public lecture and demonstration at Toynbee Hall in London, during which he repeatedly pressed a key on one black box (the spark-gap transmitter), which caused a bell to ring on another black box (the coherer), which Marconi himself carried around the lecture hall, trailing "dings" behind him, with no wires anywhere (first and third images). This was sensational stuff.

Marconi subsequently received funding from the GPO that allowed him to build large transmitters at places like the Isle of Wight, where he was able to send signals to ships several miles away, and before long even across the English Channel. A big breakthrough came when he discovered that a vertical mast antenna that was grounded to earth greatly increased the range to a receiver that was also grounded. He built such an antenna along with a transmitter and receiver, in Cornwall, at Poldhu Point (fifth image). In 1899, Marconi made his first trip to America, where he was well received in New York City, now all of 25 years old. His impeccable English helped make a good impression on everyone. On his return trip to England, he transmitted regularly from shipboard, and the receiver at Poldhu first picked up his transmissions when he was 68 miles away, a record at the time.

Marconi returned to the U.S. in late 1900, with secret plans to attempt wireless telegraphy across the Atlantic. He installed a receiver on Signal Hill at St. John’s, Newfoundland, with antennas held up by kites, and at a prearranged time on Dec. 12, 1901, he and his assistant both thought they detected a Morse-code S (three dots) sent from Poldhu Point, some 2200 miles away. Marconi had such a high reputation that when it was announced that a wireless signal had been sent across the Atlantic and detected, it was immediately accepted as fact by nearly everyone, and Marconi became an international hero. We now know that it is highly unlikely that a transmission of that power and wavelength would make it across the Atlantic during daylight, so it is probable that Marconi and his assistant just thought they heard 3 faint clicks in their headphones. But no one seems to hold that against Marconi, as there is no doubt that he later made successful trans-Atlantic transmissions – it just probably wasn’t on Dec. 12, 1901.

Marconi received a share of the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1909 for what we would now call the invention of radio. The company he had set up in 1897, which became the Marconi Co., was a leading force in the development of radio in the first two decades of the 20th century. Marconi died on July 20, 1937, in Rome, after a long series of heart attacks; he was 63 years old. His mausoleum is too gaudy for me to show; I prefer the 2000 lire banknotes that Italy issued in his honor in 1990 (last image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.