Scientist of the Day - Hans Christian Oersted

On Apr. 21, 1820, according to tradition, the Danish experimental physicist Hans Christian Oersted (Ørsted to the Danes) made a famous accidental discovery in the classroom that launched the age of electromagnetism. Ever since William Gilbert in 1600 had noted the similarity between the electrical attraction of amber and the magnetic attraction of the lodestone, natural philosophers had been trying to find some connection between electricity and magnetism. The search intensified after 1800, when Alessandro Volta invented his “pile”, or battery, for it was now possible to send continuous electrical current through a wire.

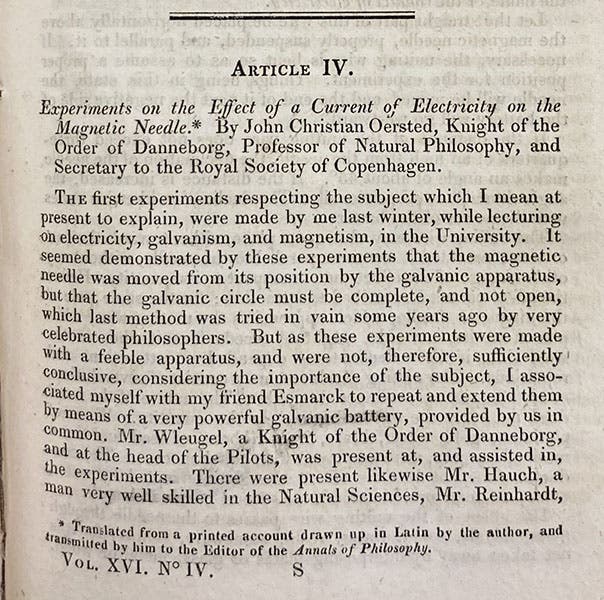

Surprisingly, no one found any magnetic effects of electrical current until this momentous day in 1820, when Oersted was giving a demonstration for some students. Oersted just happened to notice that when a circuit was closed, electrifying a wire, the needle of a nearby compass jumped. Investigating the matter in the following months, Oersted found that an electric current generates a circular magnetic field around a wire, which one can map out with a compass. He announced his discovery on July 21, 1820, in a four-page pamphlet called Experimenta circa effectum conflictus electrici in acvum magneticam (Experiments on the Effect of an Electrical Current on the Magnetic Needle). This publication certainly galvanized the scientific community, as it introduced a new field, electromagnetism, into the domain of physics. Oersted's Latin pamphlet is very scarce – there are only several copies in the United States – but within a few months, translations were published in a handful of journals, Including the Annals of Philosophy (whose founder and editor, Thomas Thomson, was our Scientist of the Day just 10 days ago). We have this journal in our Library, and we show you the first page of the translation of Oersted’s pamphlet (fourth image).

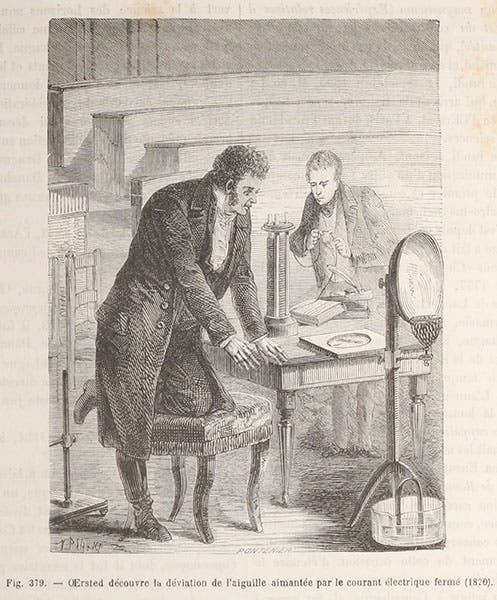

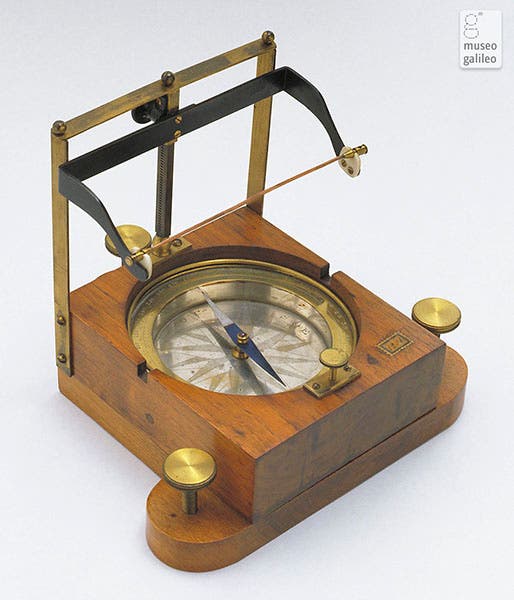

There is not a lot of graphic dressing for this important bit of scientific serendipity. The original compass that Oersted used to make his discovery is supposedly still preserved in Copenhagen, but there is no image available anywhere online. There is a later demonstration compass, made in 1828 in London to display Oersted’s discovery, on display in the Science Museum in London (first image). A slightly more elegant device, made around 1850 for the same purpose, is on exhibit in the Museo Galileo in Florence (fifth image). And fifty years after the fact, the French science historian Louis Figuier tried to recreate the demonstration in a wood engraving (third image). The object on the table between Oersted and his assistant is a Voltaic pile, to which the assistant is connecting the wire that will deflect the compass, although in the engraving, the wire is probably too far away to have much effect.

If we allow ourselves to use modern images, there is an educational animation of Oersted’s experiment of discovery on a webpage of the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory in Florida.

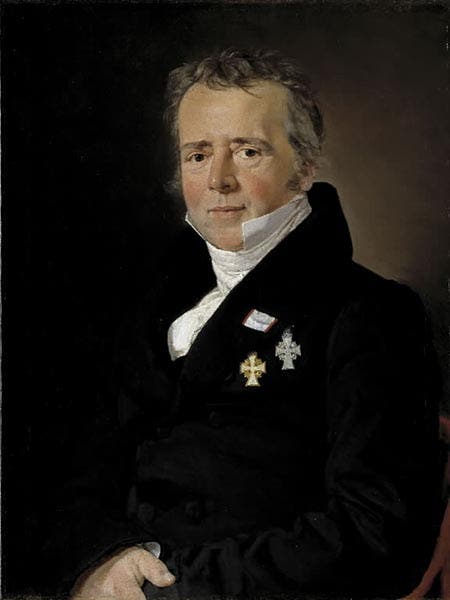

As for images of Oersted himself, we are a little more fortunate. Oersted was an important part of what is called the Danish Golden Age of the early 19th century – he was good friends, for example, with Hans Christian Andersen – and so we have at least one good portrait of Oersted, by the Golden Age artist Christian Albrecht Jensen, which is in the Danish National Gallery in Copenhagen (second image). In his later years, Oersted became a scientific ambassador for his country and was quite popular with Danish citizens; when he died in 1851, it was said that hundreds of thousands of people joined the funeral procession. Copenhagen established a public park in his honor, Oersted Park, and it contains a statue of Oersted by what I suppose we should call the Silver Age sculptor, Jens Adolf Jerichau (sixth image). The three figures around the base of the statue represent Urd, Verdande, and Skuld – Past, Present, and Future.

Oersted was buried with a simple headstone in the Assistens Cemetery near Copenhagen, which also contains the remains of Andersen, Søren Kierkegaard, and physicist Niels Bohr.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![Andromeda and Perseus, constellations figured by James Thornhill, with star positions determined by John Flamsteed, in Atlas coelestis, plate [15], 1729 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/1b30cfec-5be6-4297-a7fb-97255ba992e5/thornhill1.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)