Scientist of the Day - Henry Oldenburg

Henry Oldenburg, a German/English diplomat turned professional correspondent, was born around 1618, in Bremen. Oldenburg undertook several diplomatic missions to England to the court of Oliver Cromwell on behalf of the city fathers of Bremen, and he decided to stay in Englqnd. In 1656, he was engaged as a tutor to a wealthy English family, seeing their son through college at Oxford and on a grand tour. It was not a great way to make a living, but he did manage to meet quite a few natural philosophers, such as the members of the Oxford Philosophical Club, including John Wilkins, John Wallis, Robert Boyle, Christopher Wren, and Robert Hooke. Most important was his friendship with Robert Boyle, a wealthy Irish gentleman at Oxford with a keen interest in experimental science (Oldenburg’s tutee was Boyle’s nephew). Boyle became a patron of Oldenburg and had him gather books and information when Oldenburg was touring Europe. On the continent, Oldenburg met Giles Roberval and Jacques Rohault in Paris, both Cartesians, although he was too late to meet Descartes himself, who had died in 1650. He also met Baruch Spinoza in Amsterdam, before returning to London and relinquishing his charge to the parents.

In November of 1660, some members of the Oxford Philosophical Club and a few London natural philosophes met at Gresham College and decided to form a philosophical society, which would meet weekly and do experiments and exchange information. At one of their December meetings, Oldenburg was successfully proposed for membership. This was the beginning of what would become the Royal Society of London. When they received their charter from the newly restored King Charles II in 1662, Oldenburg was installed as one of the two secretaries of the Society. Since one of the terms of the charter called for the exchange of information with other learned societies, Oldenburg began writing letters almost immediately, although none of the letters written before 1662 have survived. But thousands of later letters do survive, and they have been published, in 13 fat volumes. They convey news of the society's doings, and in turn they ask for return news, from members of the Cimento Academy in Florence, and the Montmort Academy in Paris, and, after it was founded in 1666, the Royal Academy of Sciences in Paris., as well as hundreds of individuals working on their own in places without scientific societies.

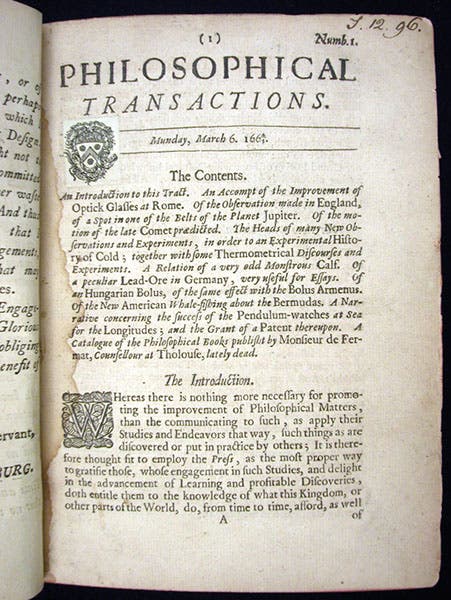

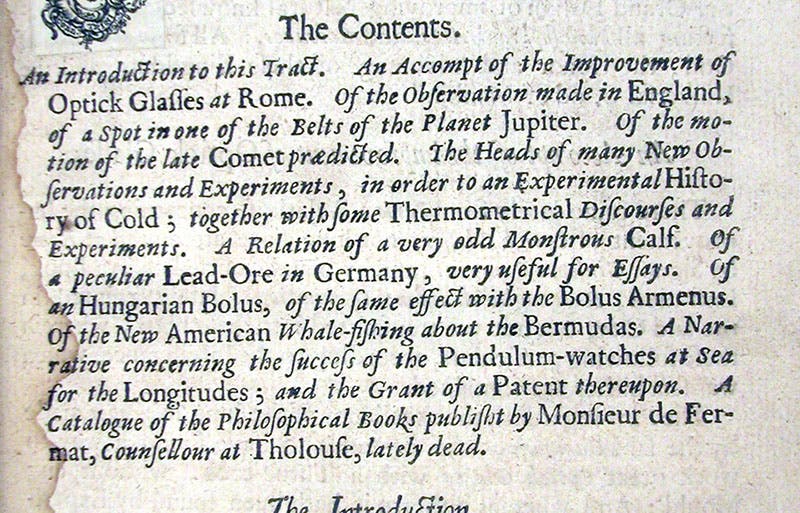

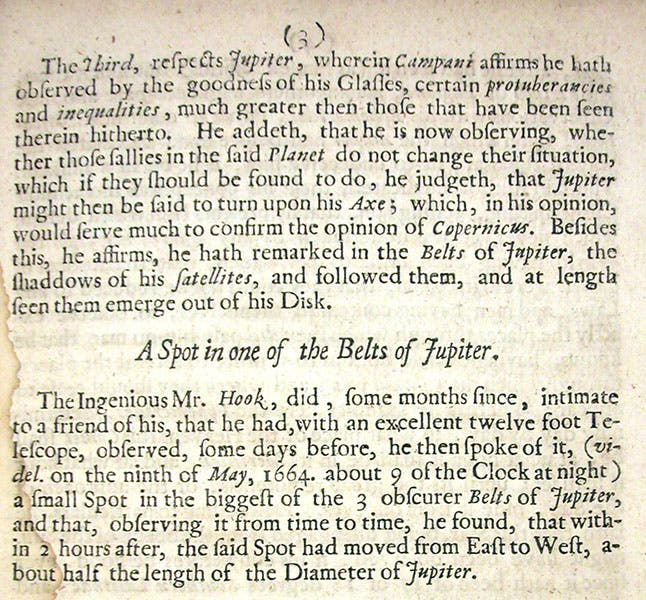

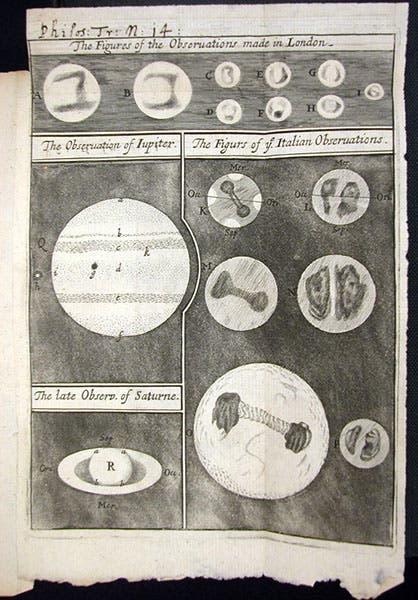

This practice of writing and sending individual letters to hundreds of correspondents was a burden to Oldenburg, who, by the way, received no salary from the Royal Society, and who had no other real source of income, other than stipends from Boyle. So after several years of writing letters, Oldenburg finally decided to print up a newsletter of sorts that detailed a month's worth of Royal Society activities and send it out to all his correspondents at once. Accordingly, on this day, Mar. 6, 1665, Oldenburg published the first issue of what he called the Philosophical Transactions (according to the modern Gregorian calendar, this was Mar. 16, but we are sticking with the printed Julian date here). The issue (second image) was 16 pages long and contained articles on some new telescopes from Italy, on observations made by Robert Hooke of a spot in one of the belts of Jupiter, and on "a very odd Monstrous Calf." We include here a detail of the table of contents of issue no. 1 (third image), and a detail of the article on Hooke and Jupiter (fourth image). A month later, Oldenburg published issue no. 2, and he kept it up, every month or so, with further issues. For many of the issues, he added an engraved plate – we show here a nice one included with issue no. 14, showing telescopic observations of Mars and Jupiter by Hooke and Giovanni Cassini in Bologna (fifth image). Little did Oldenburg know at the time that he had set several gigantic wheels in motion with this simple publishing act. He had, first of all, invented a new vehicle for publishing scientific discoveries – the journal, which would rapidly replace the book/monograph as the preferred means of announcing a new discovery, and it would maintain that status until the early 21st century and the advent of electronic publishing.

And as it has turned out, Oldenburg had also published, on Mar. 6, 1665, the first issue of what is now the world's oldest continuously published scientific journal, every issue of which, I do believe, can be found in the serials stacks of the Linda Hall Library (except for issue no. 1, which is kept in the vault, along with the other issues of the first several volumes). In fact, we have three sets of the Phil Trans, as it is referred to by historians and librarians, added as we acquired various libraries, such as the Engineering Societies Library of New York.

Oldenburg kept his position as secretary and editor of the Phil Trans right up until his sudden death on Sep. 5, 1677, at age 59 or so. The journal had a few rough moments after Oldenburg’s death, but Robert Hooke kept it afloat until more regular publication could resume, and it has been a scientific staple ever since.

Oldenburg was fluent in German, Dutch, French, English, and Latin, so he was able to translate most correspondence from abroad for publication in the Phil Trans, such as Antoni van Leeuwenhoek’s many letters on his microscopical investigations, and the writings of Johannes Hevelius of Gdansk, who was another frequent correspondent, and Marcello Malpighi of Bologna. Usually his translating work was unacknowledged, but on at least one occasion, he took credit for this part of his job. The Prodromus of Nicolaus Steno, the founding book of historical geology and stratigraphy, was published in Latin in Florence in 1669. The book was hard to obtain in England, and the printer of the Latin text apparently wrote to Oldenburg and suggested that he have it translated and circulated. Oldenburg did just that, and acknowledged on the title page that it was “English’d by H.O.” (sixth image).

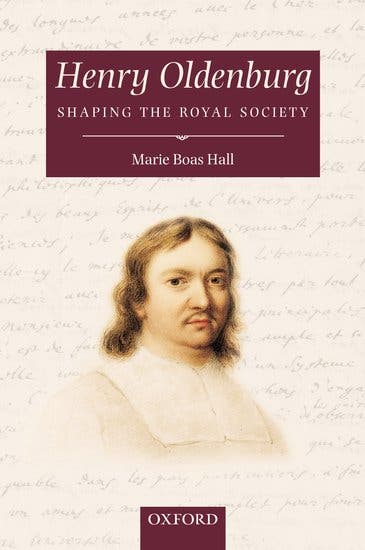

An excellent account of Oldenburg’s life and career may be found in Henry Oldenburg: Shaping the Royal Society (2002), by Marie Boas Hall, who, with her husband, edited the 13 volumes of Oldenburg’s correspondence. The dust jacket (sixth image)is graced with a pastel portrait of Oldenburg, made by John Bradley in 1838, after the portrait by Jan van Cleve that is in the Royal Society of London (first image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![Title page, The Prodromus to a Dissertation, by Nicolaus Steno, “English’d by H.O.” [Henry Oldenburg], 1671 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/1b6aa178-8e95-4494-8a19-d9b0d7ab80aa/oldenburg6.jpg?w=401&h=600&auto=format&q=75&fit=crop)