Scientist of the Day - Heraclitus of Ephesus

Heraclitus of Ephesus was a pre-Socratic natural philosopher who was born about 540 B.C.E. in Ephesus in Ionia, on the west coast of Asia Minor. Ephesus was a thriving city, in which a temple to Artemis was being built as Heraclitus grew up (and of which only a few stones remain, second image). It is not clear how much Heraclitus knew of his philosophical forebears, the Milesian trio of Thales, Anaximenes, and Anaximander, but he must have known something, for he followed in their philosophical path, seeking to understand the logos or reason of the cosmos, and avoiding supernatural explanations. He differed from the Milesians in that he left behind a modest body of work in the form of aphorisms, over 130 of them, which take up quite a few pages in Freeman's Ancilla to the Pre-Socratic Philosophers. Not only do these fragments give us a better idea of what Heraclitus thought, we also get a better picture of Heraclitus the man, who, as it turns out, was something of a curmudgeon and an intellectual snob. If we recall that in Heraclitus’s day, Homer and Hesiod were revered figures, it is a little shocking to read: "The learning of many things does not teach one understanding, or else it would have taught Hesiod and Pythagoras, and Xenophanes and Hecataeus," or, more succinctly, "Homer should be flung out of the contests and given a beating."

A stone column and some fragments, all that remains of the Temple of Artemis, Ephesus, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World (Wikimedia commons)

As far as natural philosophy goes, Heraclitus is noted for observing that the most significant feature of the world is the fact that it is always changing. What appears stable, is, in truth, in constant flux. By far the most famous aphorism of Heraclitus, one you can find in Bartlett's Book of Quotations, states: "You cannot step twice into the same river." This is not only a profound observation, but memorably phrased. You step in a river one day, and then do so again the next, and you might think that you have simply done the same thing over again, but in fact every drop of water in that river, and every grain of sand in the riverbed, is different than it was the day before. So if we want to understand the world, we have to understand the nature of change. And then we have to figure out why, if the world is always changing, there seems to be an underlying stability, in spite of the constant flux. This becomes the fundamental problem for philosophy – how do change and stability coexist, so that all is not chaos in the world?

Heraclitus, like the Milesians, was also a monist, meaning that he believed that the world evolved from a single preexisting substance. Heralitus did not choose water, or air, or apeiron, the preferences of the Milesians, but rather opted for fire as the basic stuff – the arche – of the universe, which is perhaps not surprising, given that fire is the most changeable of elements.

If Heraclitus had pupils, we don't know about them. But he did have later admirers, especially the Stoics, which is why so many of his fragments have survived. When the Greek word logos later became an important term in both philosophy and religion (“In the beginning was the logos," began the gospel of John), it was recognized that the term originated with Heraclitus, but no one can quite figure out what he meant by logos, whether “reason,” or “order,” or “meaning,” although Heraclitus observed that most people live as though they are unaware of the existence of a logos.

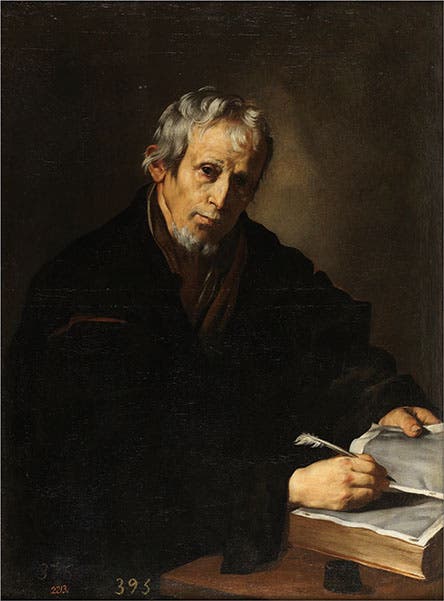

Needless to say, but we say it anyway, we have no idea what Heraclitus looked like, but you will find his portrait in Wikipedia and other encyclopedic articles anyway, and we reproduce it here, if only to make the point, this is certainly not a portrait of Heraclitus (first image). This is a bronze bust in the National Archaeological Museum in Naples – how it got assigned to Heraclitus, no one knows. It is a handsome bust, but you will also find it used for other ancient Greeks, especially Democritus, the atomist. And speaking of Democritus, he and Heraclitus were identified by a much later Greek writer as exemplifying the Laughing Philosopher (Democritus) and the Weeping Philosopher (Heraclitus). That seems incredibly inane, but like many dumb ideas, it had legs, and the Laughing and Weeping Philosophers became a common motif in late Renaissance art, the best-known exemplar being a painting by Peter Paul Rubens. We prefer a work that just shows the Weeping Philosopher, Heraclitus, a painting by Jusepe de Ribera , known as Lo Spagnoletto, in the Prado (third image).

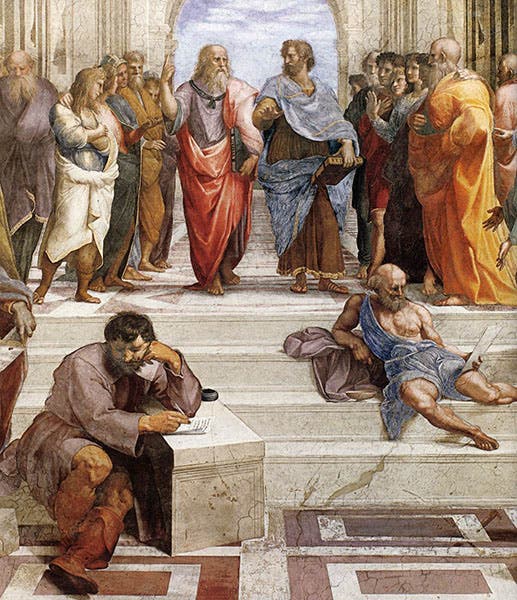

When I want to picture Heraclitus, I think of the melancholy seated figure in the left foreground of Raphael’s The School of Athens (1510-11) in the Stanza della Segnatura in the Vatican (fourth image, above; detail in fifth image, below). Leaning on a block of marble and writing down fragments, he is all alone in his world of change. Everyone agrees that this is Heraclitus, although I am not sure why, since Raphael himself never identified any of the subjects in the fresco. But it does seem to fit the moody Heraclitus. Since it is said that this figure was modelled after Michelangelo, I can think of no better way to be memorialized.

Heraclitus was the last of the Ionian philosophers. The next significant pre-Socratic thinkers will be found in Elea, in Magna Graecia, on the southern Italian peninsula. Parmenides of Elea will be our next stop, unless we detour through Croton, also in Magna Graecia, where Pythagoras and the Pythagoreans had also taken up residence.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.