Scientist of the Day - HMS Challenger

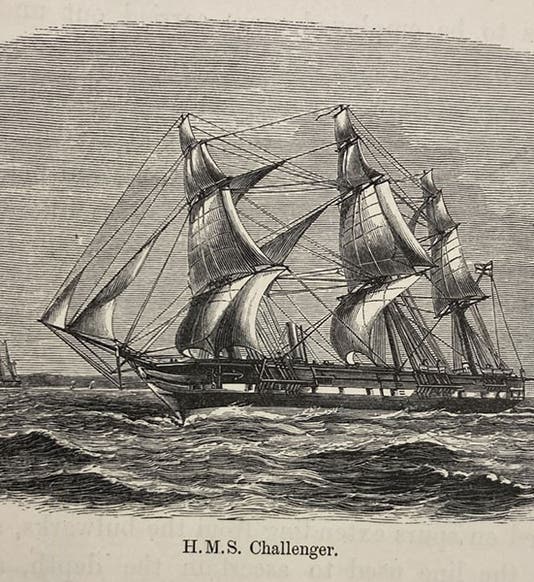

HMS Challenger, on loan from the British Royal Navy, staffed with a crew of 237 and a scientific contingent of six, sailed from Portsmouth, England, on Dec. 21, 1872, on a voyage that was to dramatically expand the nature and scope of scientific exploration. The mission of the Challenger expedition was to explore the depths of the ocean around the world, mapping the sea floor and dredging for new forms of life from the bottom of the sea. It was a seminal event in both oceanography and deep-sea marine biology.

The voyage was the brainchild of William Benjamin Carpenter, a physiologist turned marine biologist, who, on behalf of the Royal Society of London, had for years tried to interest the British government in sponsoring such a voyage. He was aided in his quest by Charles Wyville Thomson, a marine biologist at the University of Edinburgh. Both men were spurred on by the discovery, in the late 1860s, that the deep sea harbors abundant forms on life. The prevailing opinion, set forth by another great marine biologist, Edward Forbes, was that the sea below about 500 fathoms is devoid of living things. The "azoic hypothsis" argued that benthic depths receive too little sunlight and oxygen and were subject to too much pressure to allow life to flourish, and that made sense to everyone. Then Carpenter and Thomson accompanied two short northern voyages in 1868 and 1870, aboard HMS Porcupine and Lightning, and dredged up all sorts of living things from thousands of fathoms down. It was clear that scientists had no idea what was down there, and equally clear that someone ought to make an effort to find out. The government finally agreed to support a world-wide oceanographic expedition, and to refit the Challenger, a ten-gun steam-and-sail warship built in 1858, for the enterprise. For a commander, they chose the exceptionally able George Nares.

The Royal Society of London selected the scientists. Since Carpenter decided (or it was decided for him) that he was too old for such an arduous voyage, Wyville Thomson was the natural choice for team leader; his staff included: Henry Nottidge Moseley, chief naturalist, and an assistant; John Buchanan, an oceanographer; and J. J. Wild, the ship’s artist. The last man to be signed up was a young Scottish oceanographer, John Murray, who turned out to be something of a miracle worker – who knows how matters would have fared without him.

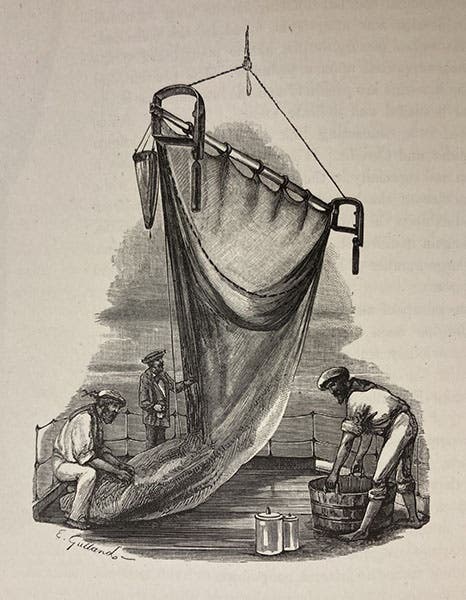

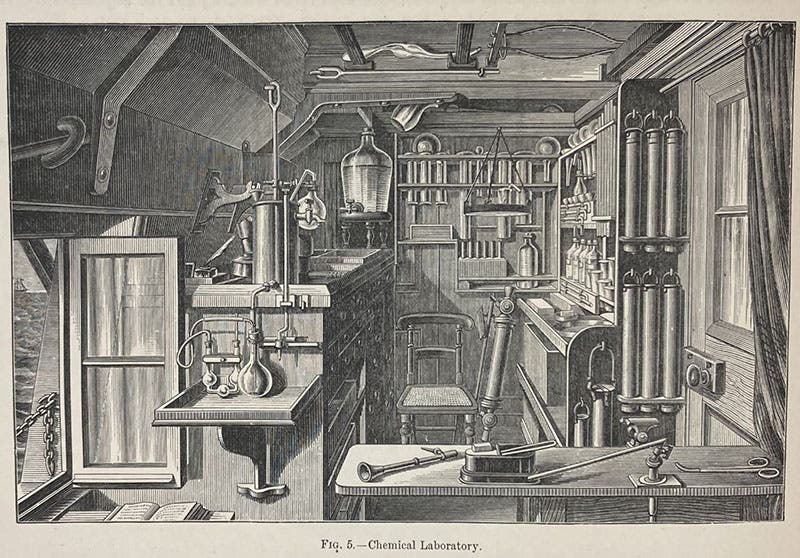

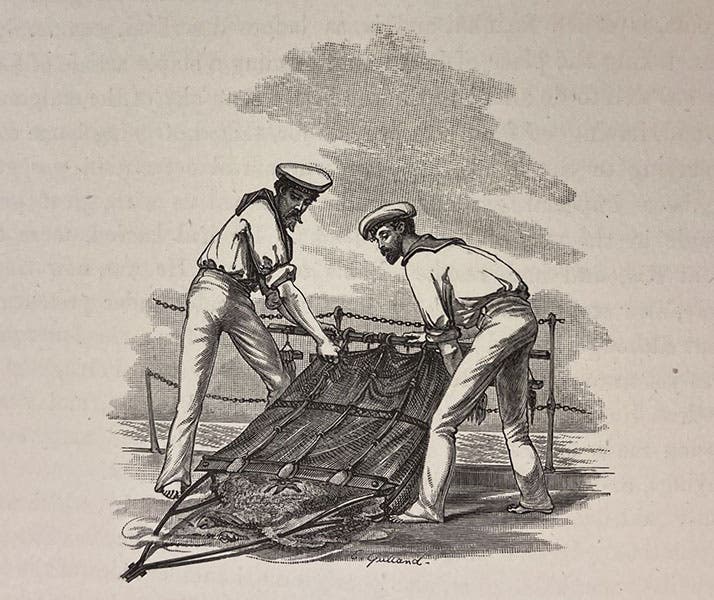

To make room for laboratories and workshops, 8 of the 10 guns were removed, with the gun bays being converted to labs and storerooms. Machinery for manipulating dredges and trawling nets was brought on board, including an engine to haul in the dredges. Space had to be found for miles and miles of hemp rope, used for dredging and for sounding the ocean bottom. Wire rope had been invented but was not yet available.

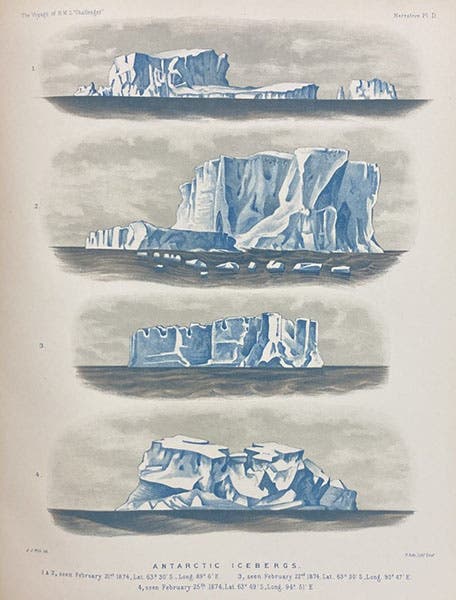

The Challenger voyage took three-and-a-half years and more than circled the globe, covering nearly 79,000 miles in its wanderings. They started in the North Atlantic, circling through the Azores and across to Bermuda, then down to the South Atlantic. The ship went east, around the Cape of Good Hope, along the southern Pacific islands and Antarctica, and then slowly sailed and steamed though much of the Pacific Ocean. They finally navigated around Cape Horn in South America and arrived back at Spithead on May 24, 1876. They had a change of captain in 1875, as Nares was pulled away by the Royal Navy to lead an Arctic expedition (which you can read about in our post on Nares), but his replacement acquitted himself well.

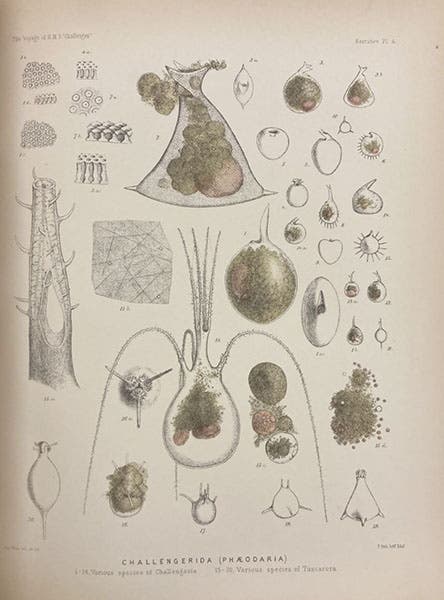

The daily routine of the Challenger was fairly boring. They set out and hauled in three or four dredges or trawling nets and made as many soundings as possible. In places where the ocean floor was several miles down, it could take a long time to lower a trawl, and haul it back in, and the same with sounding lines. Often there was nothing to show but muck for four hours’ work. But often enough, some new kind of creature was found in the net, so that by the time they were done, they had found over 4500 species unknown to scientists before the Challenger went out.

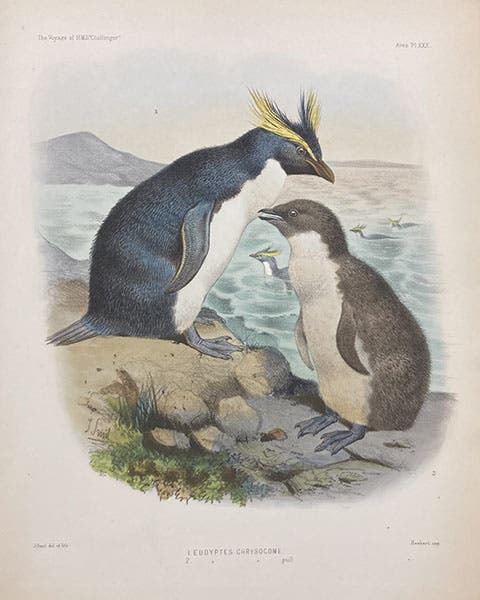

When the expedition returned, Thomson undertook the massive task of editing the scientific results, but the publication enterprise weighed too heavily on his shoulders, and he broke down, and eventually died. The editorial task was taken over by Murray, who successfully completed the Report in 1895, after fifteen years’ work. The Report totals exactly fifty fat quarto volumes, and we have every one of them, I do believe, in our Closed Stacks. The images for this post were mostly taken from volume 1 of the Narrative, and include headpieces, tailpieces, text engravings and chromolithograph plates. I pulled one of the zoology volumes off the shelf and was lucky to discover that it contained several plates of birds at the end, by the artist Joseph Smit, who did not go on the voyage, and so I included his painting of a rockhopper penguin, just because it appealed to me.

We have published a post on Wyville Thomson and one on John Murray, as well as one on Nares, but we have not yet written on Carpenter, Moseley, or the on-board artist, John James Wild, who was an odd duck. We shall do so in the future, which will give us other occasions to plumb the untapped riches of the volumes of the Challenger Expedition Report.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![Andromeda and Perseus, constellations figured by James Thornhill, with star positions determined by John Flamsteed, in Atlas coelestis, plate [15], 1729 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/1b30cfec-5be6-4297-a7fb-97255ba992e5/thornhill1.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)