Scientist of the Day - James Bond

James Bond, an American ornithologist, was born Jan. 4, 1900, in Philadelphia. He was educated in England, where his family moved when he was 12, studying economics at Trinity College, Cambridge, but he returned to Philadelphia in 1922 and took up a job as a banker. Life at a desk did not please him. In 1925, he decided to join a friend on a collecting trip to South America, where he discovered his true calling - collecting and studying birds. When they returned, the two adventurers sold some of their specimens to the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia, thus establishing for Bond a relationship with that institution that would last his entire life. Bond was for a long time an Associate Curator of Birds, and would eventually become Curator of Birds in 1962.

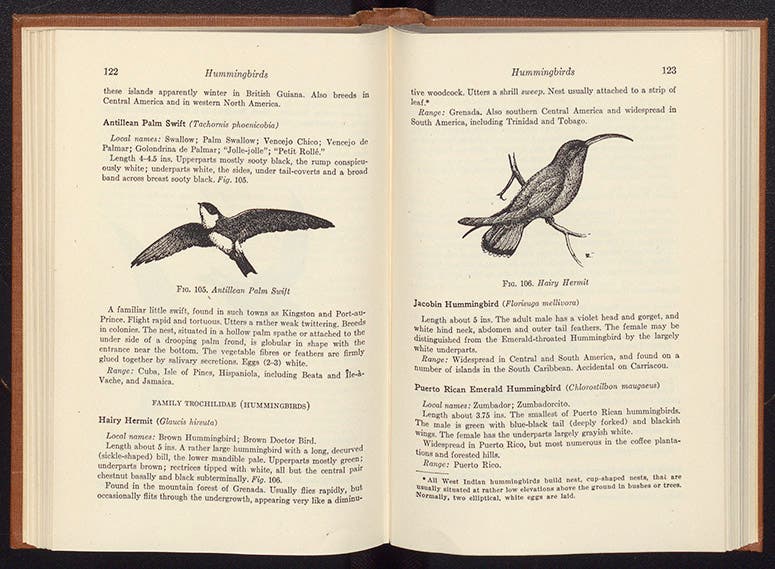

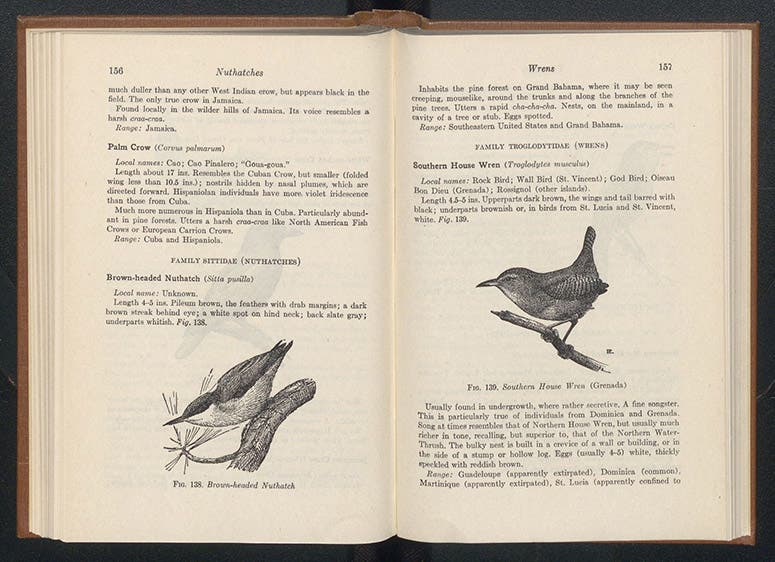

Bond decided to concentrate on the birds of the Caribbean – perhaps because they were closer than the birds of Amazonia, perhaps because, as he later said, the birds of the Caribbean are in greater danger of extinction than any other birds of the New World. He made many collecting trips to the islands of the Caribbean, where he personally collected all but six of the 300 native birds. In 1936, the Academy published his Birds of the West Indies. A decade later, the book was reissued by a commercial press and garnered a much wider circulation. We do not have the 1936 Academy edition in our Library, but we do have the 1947 edition published by Macmillan as Field Guide to the Birds of the West Indies, and we show here some openings from that book – the Antillean Palm Swift and Hairy Hermit hummingbird, from one pair of pages, and the Brown-headed Nuthatch and Southern House Wren from another (second and third images, above). Much later (1986), Bond’s field guide would become part of the famous Peterson Field Guide series.

One of the fans of Bond's book was an English amateur bird watcher who maintained a residence in Jamaica, Ian Fleming. Bond's Birds of the West Indies was one of his "bibles," as he called it. Some years later, in 1952, Fleming was casting about for a name for the hero of the spy-thriller he was writing. He wanted the name to be "brief, unromantic, and yet very masculine," and he decided that James Bond was the perfect bland moniker for his dashing secret agent. Casino Royale was published in 1953, and soon James Bond was a household name. The ornithologist Bond does not seem to have minded sharing his name, and in 1964, the two met at Fleming's Jamaican house. Fleming presented ornithologist Bond with a copy of You Only Live Twice (1964), inscribed "To the real James Bond, from the thief of his identity." After Bond's death, his wife Mary gave most of her husband's papers to the Academy, but perhaps because the inscribed Fleming book was not a work of science, she did not include it in her gift to the Academy. It eventually went to auction – twice – the last time in Hollywood in 2008, where it sold for $70,000. Had Mrs. Bond given it to the Academy with the rest of his papers, you and I would still be able to see it. But alas, we cannot!

James Bond (left) and Ian Fleming, at Fleming’s house in Jamaica, photograph, 1964 (courtesy of Robert M. Peck and the archives of the Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia)

Incidentally, if you have access to a much later Bond film, Die Another Day (2002), fast forward to the scene where Pierce Brosnan is walking around the office of Bond’s local contact in Cuba, looking at books (scene 10 on my DVD), and happens to pick up and examine a copy of Birds of the West Indies. Bond meets Bond! Script writers and directors have such a good time burying morsels like this in their movies; it is too bad we miss nearly all of them.

There is a discussion of ornithologist James Bond in A Glorious Enterprise (2012), a history of the Academy of Natural Sciences, by Robert McCracken Peck and Patricia Tyson Stroud. Bob Peck, whom I have known for a long time, is a Senior Fellow at the Academy, and a well-traveled ornithologist himself; he wrote the section on Bond, from which I drew for my own brief account here, and for which I am grateful. A Glorious Enterprise is a book well worth seeking out (just make sure you have a substantial library table to hold it!), not only for its rich narrative, filled with 200 years of the adventures of academy members, but for its wonderful photographs, taken for the occasion by the inimitable Rosamond Purcell.

We also have in our collections a copy of Bond’s Check-list of Birds of the West Indies, which I mention and illustrate here, because we have the original 1945 Academy publication of this Bond book.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.