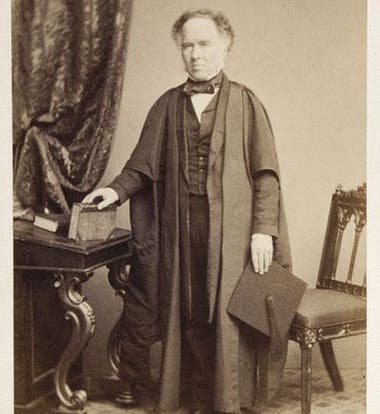

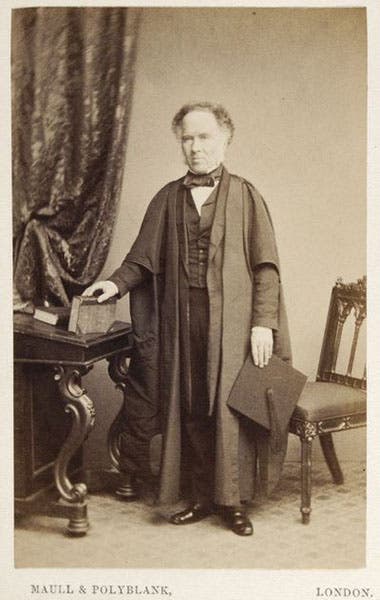

Scientist of the Day - James Challis

James Challis, an English astronomer, died Dec. 3, 1882, just shy of his 79th birthday. Challis was clearly a bright fellow, for he attended Trinity College, Cambridge, was Senior Wrangler there, and was elected a Fellow at Trinity immediately after graduation in 1825. He was also ordained in 1830. In 1836, after George Airy left Cambridge Observatory to become Astronomer Royal, Challis succeeded to the Directorship, at the same time becoming Plumian professor of astronomy. His career was off to a promising start. And then came the events of 1845-46.

Challis is somewhat infamous in the halls of astronomy as the man who had a golden chance to discover Neptune, and failed to do so. John Couch Adams had supposedly predicted the position of an eighth planet in the fall of 1845, a prediction that Challis purportedly ignored, until the summer of 1846, when Challis was instructed to search for it by Airy. He did so, for about a month, but failed to find the planet. A Frenchman, Urbain Le Verrier, made an independent prediction that same summer, sent it to Berlin, and Neptune was discovered the very night of receipt of the prediction, Sep. 23, 1846.

The article on Challis in the Dictionary of Scientific Biography calls him "a spectacular failure as a scientist," and further says "the events surrounding the discovery of Neptune [gave] him a genuine opportunity for scientific immortality, but he fumbled it ." However, it turns out there was a fat file documenting the events of 1845-46, kept by the Astronomer Royal – a file that had gone missing from the Royal Observatory archives in the 1960s and was thus unavailable to scholars. The file finally turned up in 1998 in South America, among the possessions of a recently deceased American astronomer, Olin Eggen, who just happened to be the author of the DSB article that called Challis a spectacular failure, and who several times had denied knowing the whereabouts of the file.

The letters that Challis wrote and published in November of 1846, when Airy was trying to make a public case for Adams as a co-discoverer of Neptune, sound very much like a mea culpa, acknowledging his own failure to search in the fall of 1845 after Adams gave him a predicted position for a new planet, and his inability to find it in the summer of 1846, even though new predictions by Adams were within a degree of Neptune's actual position. But the Neptune file tells us that Adams may not have made a prediction at all in 1845, and that the predictions he made in the summer of 1846 were constantly changing, so Challis had no chance of finding Neptune. One scholar who has recently studied the entire file calls the story of Adams' independent prediction of Neptune’s position a deliberate fabrication, concocted by Airy and Challis to salvage English pride in the face of French success, even though it cost Challis and Airy their reputations, and gave Adams a credit that he did not deserve.

If Challis did misremember his interactions with Adams and Airy in order to make a better case for Adams as co-discoverer of Neptune, then he deserves the poor reputation he has today, only it should be for prevarication rather than incompetence. Adams later succeeded Challis as Director of Cambridge Observatory. I hope he gave Challis a substantial Christmas ham every year, for he would never have been in that position, had Challis not reconstructed his memories in order to advance the cause of Adams.

We have told the story of Adams and Neptune several times before, in posts on John Couch Adams and George Biddell Airy.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.