Scientist of the Day - James Keeler

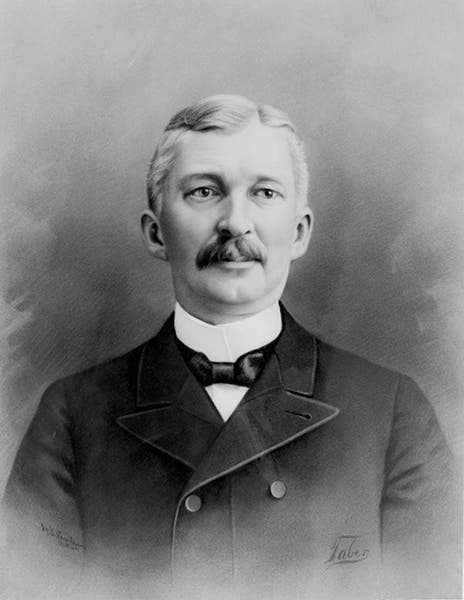

James Edward Keeler, an American astronomer, was born Sep. 10, 1857, in Illinois, moving to Florida after the Civil War. He had a mechanical gift, and he built his own telescope (using catalog-bought lenses) as a teen and used it to observe the planets and stars. He enrolled in the newly founded Johns Hopkins University and studied astronomy under the great Simon Newcomb, who was impressed by young Keeler and would later recommend him for positions. Keeler went to work first for Samuel P. Langley at the Allegheny Observatory in Pittsburgh (where the benefactor of Allegheny, William Thaw, paid for Keller to study spectroscopy and optics for a year in Germany). Then Keeler was hired in 1888 by the newly opened Lick Observatory at Mount Hamilton, an hour east of San Jose, California, which had the world's largest telescope (for the moment), a 36-inch Alvan Clark & Sons refractor, with which Keeler promptly discovered a new gap in Saturn’s outer ring. The gap he discovered (following Stigler's law) is called the Encke gap, but an A-ring division discovered much later (by a Voyager spacecraft) is now called the Keeler gap, so Keeler is an eponym once removed.

As he did not get along well with the Director of Lick Observatory, Edward Holden (no one got along with Holden), Keeler moved back to Allegheny Observatory in 1891 to become director there, after Langley had moved to Washington to become Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. Keeler was an excellent observational astronomer and a skilled photographer and spectroscopist, so his skills were always in demand. When Holden was forced out at Mount Hamilton (or resigned, take your pick), the regents took their time looking for a replacement, and they homed in on Keeler. He agreed to become Lick Observatory director in 1898.

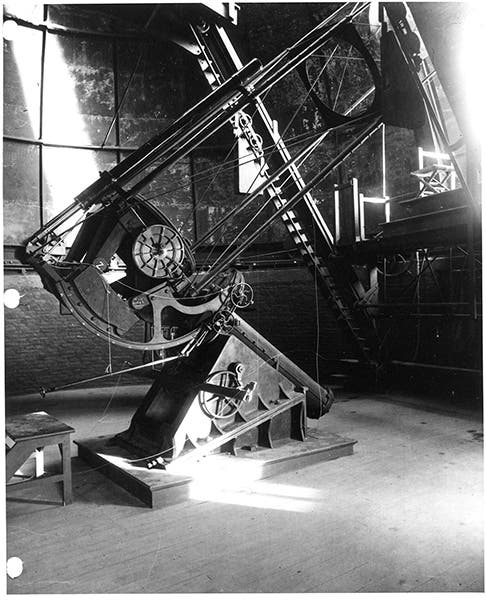

When he took over, Keeler had a delicate path to tread, since the observatory staff was thoroughly disgruntled, after years of Holden, but Keeler’s tact, intelligence, and astronomical abilities won everyone over. One possibly thorny problem was the 36-inch Crossley reflector, which Holden had acquired from an Englishman who had bought it from A. A. Common, who had had it built (fourth image). It was the largest reflector in the world, but the mirror surface was bad, and the mount was a mess. Holden, who acquired it, made no personal effort to fix it up, and the men he assigned to the task of making it serviceable greatly resented it, since they would rather have been given time on the giant refractor.

Keeler knew that whomever he assigned to the Crossley would take it badly, so he took on the project himself, relieving everyone and earning him considerable brownie points. And he was just the man to restore it, since he had such a great understanding of the mechanics of telescopes and their drives. Holden had never recognized that the telescope mount had a polar axis that was still aligned to the latitude of London, which meant its clock drive could not properly track stars at the latitude of Mount Hamilton. Keeler realized this right away. He had the mount rebuilt, the polar axis realigned, and the mirror re-silvered. He also spent hundreds of hours figuring out how to overcome the Crossley’s idiosyncrasies and operate it smoothly.

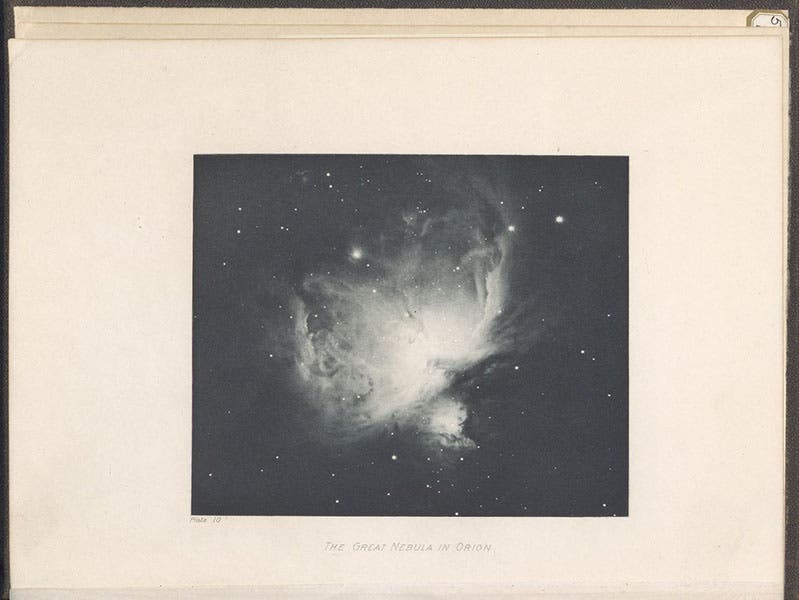

Beginning in 1899, Keeler started taking long-exposure photographs of nebulae with the Crossley reflector. They are exquisite, the best deep-sky photographs ever taken to that time. We include six of those here. The Great Nebula in Orion was a very popular target for astrophotographers at the time; you can compare Keeler’s exposure (fourth image) with one taken by Common himself, with the same telescope, 16 years earlier, at our post on Common.

Keeler was especially fascinated with spiral nebulae, which most astronomers of the time thought were solar systems in formation, and thus not very far away. M74 is a spiral (fifth image), as is M81 (sixth image), and so of course is M31, the giant nebula in Andromeda (first image), and Keeler took stunning photographs of all three. The surprise was that each of these photographs contains hundreds of tiny blobs that seem to be spirals seen obliquely, or even edge on. Keeler didn’t know what these spirals were – astronomers would not begin to figure out that they are galaxies like the Milky Way until after 1920 (see our posts on Heber Curtis and Edwin Hubble) – but Keeler showed they are everywhere, probably important clues to understanding our universe, as indeed they are.

The last two Keeler photographs we show depict gaseous nebulae. The first, M20 in Sagittarius, we include just because it is so spectacular in black and white (seventh image). Our last image is also striking, but for a different reason. It shows M1 in Taurus, which is unlike any other Messier object (those that start with a M prefix). It looks like it has exploded, which indeed it has, although no one knew that in Keeler’s time. We know now that M1 is a supernova remnant, an expanding cloud of gas and dust from an explosion that was observed on Earth in 1054 AD. When astronomers had figured this out and wanted to determine the rate of expansion, they looked for the earliest existing photograph that had consistent focus and sufficient resolution to be used as a starting point. They found it in this photograph by Keeler.

Keeler’s future as Director of Lick Observatory seemed bright indeed, but after a tenure of only two years, he began to show symptoms of an undiagnosed heart defect, rapidly lost his strength, and died on Aug. 12, 1900. He was not yet 43 years old. Astronomers everywhere were shocked and saddened. His friends and colleagues saw to it that the best of his nebula photographs were published; Photographs of Nebulae and Clusters Made with the Crossley Reflector appeared in 1908 as volume 8 of the Publications of the Observatory, and also as a separate monograph. We have both versions in our collections, and we show images from the separate publication that is part of our History of Science collection.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.