Scientist of the Day - James Vauloue

The first Westminster Bridge across the Thames in London opened on Nov. 18, 1750. It took 13 years to build, and was opposed by many interests, especially the watermen who earned their livelihood ferrying people across the river. But the bridge provided welcome relief for the crowding on the other Thames bridges, such as London Bridge, and became quite popular. Many artists painted views of it, including Canaletto, who had a good imagination, since the bridge was 3 years from completion when he depicted it (first image). This painting is in the Yale Center for British Art (YCBA), which has scores of paintings, engravings, and drawings of Westminster Bridge. You can browse them all at this link.

The Westminster Bridge was built by Charles Labelye, a Swiss engineer working in London. Since I don't know much about Labelye, I am going to turn the spotlight on a watchmaker who invented a device that greatly speeded up construction of the bridge. His name was James Vauloue, and he invented the semi-automatic pile driver.

Pile drivers had been in use for hundreds of years. A pile driver is simply a derrick holding a pulley from which hangs a heavy weight on a rope. A gang of men, usually with a web of ropes, haul the weight to the top of the derrick and let go. If the weight is positioned over a pile timber, it will impart a considerable moment to the pile, driving it down. Meanwhile, the men collect the rope or ropes and haul the weight to the top once more.

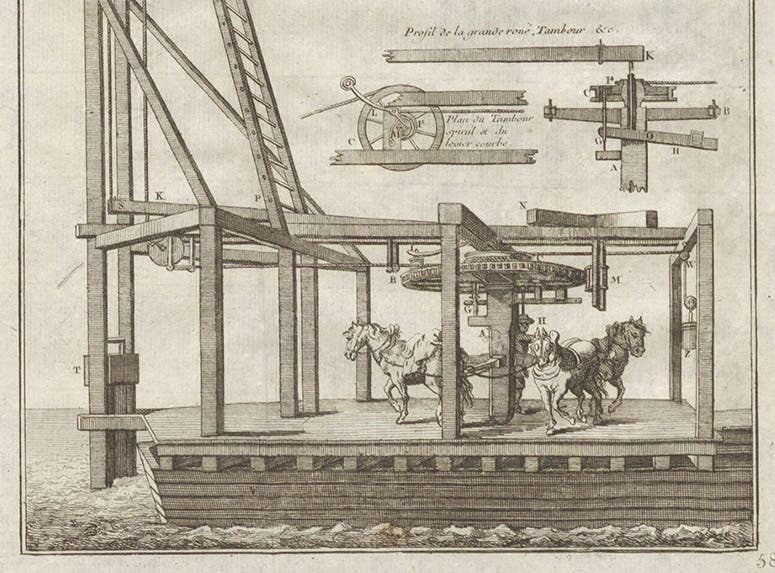

This is slow, laborious work. Vauloue’s device used horses to raise the weight. But the crucial inventions were a set of grapple-tongs, which latched onto an attachment on the weight after it had fallen, and then automatically released it when it got to the top. The other essential element, the workings of which I do it fully understand, kept tension on the rope after the weight was released, so that the horses did not go flying when the load disappeared, but just kept plodding in a circle.

Vauloue’s pile driver, it is said, could provide an impulse every 25 seconds, enabling a pile to be driven in an hour or two. It was apparently quite a crowd-pleaser, with its: creak-creak-(sound of horses breathing)-creak-creak-WHOMP! Vauloue became a popular figure, and was awarded the Royal Society’s Copley medal for his invention.

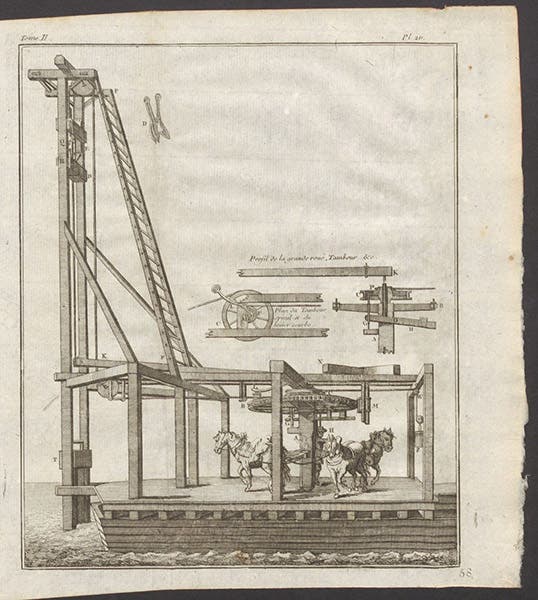

A broadside illustrating Vauloue's machine, with a detailed descriptive caption, was published in 1737 – there are copies in the Science Museum in London and the Musée des Arts et Metiers in Paris and elsewhere. We prefer to show essentially the same engraving (without the caption) that is included in our copy of Cours de physique expérimentale, by John Theophilus Desaguliers (1751; second image). We also show a detail of the horses’ domain, which includes inset diagrams of several of the working mechanisms (third image).

Most of the paintings of Westminster Bridge show the span after completion, but an artist named Samuel Scott began painting the bridge in the early 1740s, when construction was just underway. In every one of his paintings, there is a Vauloue pile driver standing at the ready. We show you one dating to 1742 that is in the YCBA (fourth image), as well as a detail of the pile driver, in case you cannot make it out in the larger view (fifth image).

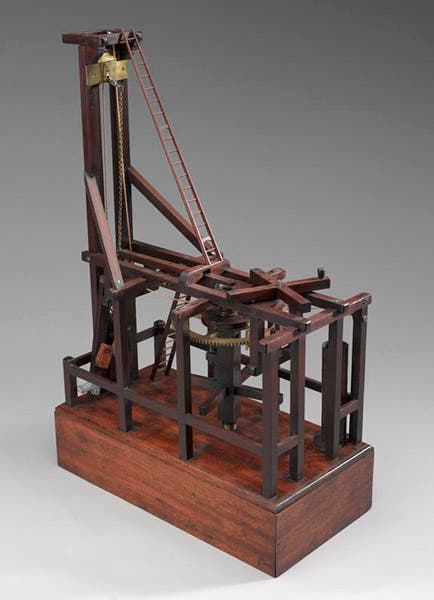

Not surprisingly, someone made a scale model of Vauloue's pile driver, which you can see in our sixth image. Very surprisingly, at least seven other craftsmen also built models, differing in their details, and usually substituting a small crank mechanism for the horses (building working miniature horses was apparently outside the skill set of most Georgian instrument makers). The one we show was built by James Ferguson and is in the Science Museum; since it was a bequest of the Patent Office, it may have been Vauloue’s patent model. Others are in Teyler’s Museum, Haarlem; the Oxford Museum of the History of Science; and the Rijksmuseum Boerhaave in Leiden.

One model that was not in any museum turned up in a garage sale in Virginia, was bought by a collector, and, 35 years later, ended up in the clutches of Kansas City's own master miniaturist, William R. Robertson. It was missing about a hundred parts, including the two ladders, two spars, and most of the hoisting mechanism, which made Bill very happy, because now he could replicate them, which he can do better than just about anyone. He even sourced some Cuban mahogany, salvaged from the original Smithsonian Building, to use for the missing wood parts. We show you the completed model (seventh image), and a detail of the fusee that controls rope tension (eighth image).

Both of these photos were taken by Mr. Robertson, and you will find dozens more on the webpage he devoted to this restoration. You really must take a look, as he provides a complete narrative of how he acquired the model and how he went about restoring it, and includes the full story of Vauloue, photos of the other 8 surviving models, and the various engravings that he used to understand how the mechanism worked. Best of all, Bill has just added a video, narrated by himself, showing his restored model in operation, raising and dropping the weight. It may be the only fully working model of Vauloue’s pile driver in existence.

For more examples of Bill Robertson’s craftsmanship, see the Gallery on his website. I am especially partial to the Gentleman’s Tool Chest and the Architect’s Classoom. The latter can be seen in person at the National Museum of Toys and Miniatures in Kansas City.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.